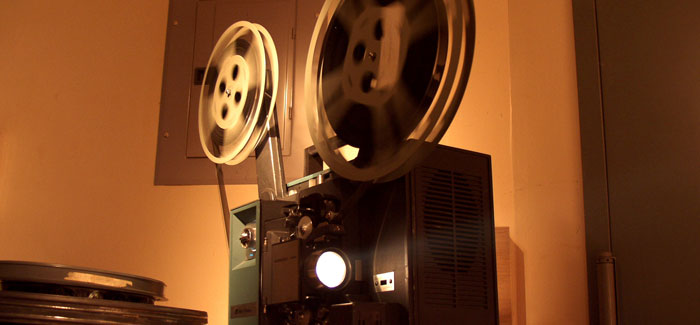

Film projector (morgueFile); Tom Gunning portrait (illustration by Allan Burch).

Film scholar Tom Gunning explains how editing conventions create the splice of life.

On the second floor of the Logan Center, Clark Gable takes off his shirt. “It was a startling moment,” says Tom Gunning, pausing the video from his laptop. “Not only to see his bare skin, but also that he wore no T-shirt.” The immediate audience for Gable’s striptease is Claudette Colbert; the film, Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night. Watching Colbert watch Gable are students in Gunning’s course History of International Cinema, Part II: Sound Era to 1960. “Sales of undershirts supposedly plummeted” after the movie’s 1934 release, Gunning adds.

On the second floor of the Logan Center, Clark Gable takes off his shirt. “It was a startling moment,” says Tom Gunning, pausing the video from his laptop. “Not only to see his bare skin, but also that he wore no T-shirt.” The immediate audience for Gable’s striptease is Claudette Colbert; the film, Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night. Watching Colbert watch Gable are students in Gunning’s course History of International Cinema, Part II: Sound Era to 1960. “Sales of undershirts supposedly plummeted” after the movie’s 1934 release, Gunning adds.

In the classroom, also Logan’s screening room, are about 25 undergraduates plus a handful of grad students. It’s third week and Gunning, the Edwin A. and Betty L. Bergman distinguished service professor of art history and cinema and media studies, has begun class talking about Fritz Lang’s M, then tacked over to Capra to highlight how differently the two directors edit. Lang, he showed, cuts from shot to shot in almost perversely idiosyncratic fashion while Capra cuts in a style that’s standard in classic (and newer) Hollywood films: continuity or invisible editing.

Gunning wants the class to think of film editing as “a theoretical and ideological process” but also a technical one. “If you look at early pictures of [Sergei] Eisenstein or [Charlie] Chaplin, they actually were working with scissors and a pot of glue.” Why emphasize the physical process? “What editing involves are two things that are complementary but almost contradictory: one, cutting something, creating a rupture; the other, joining something, splicing it together. … And there are many, many styles by which one can do this.” Film theorists in the silent era considered editing to be the essence of cinema. “That was how films told stories. That was how films developed characters. That was how films, according to Eisenstein, could even imitate ideas, issue ideas, control emotions, control space and time.”

The continuity style of editing creates a seamless narrative flow. It is not Lang’s style. His 1931 police procedural about the hunt for a child murderer in Berlin defies viewer expectations. “I’m not sure there’s anyone,” Gunning says, “who’s made a film like M. Let me give you an example. Who’s the main character in M?”

“The murderer?” ventures one student. “OK,” says Gunning. “But we don’t even see him and we definitely don’t hear him talk for most of the film. … He certainly isn’t the protagonist, and he isn’t the person who’s on screen the most. Who else could be the main character? Any ideas?”

Another student half raises her hand. “I read this somewhere, so it’s not original, but the city is a character.” Gunning nods and says, “The other person who would be the obvious candidate is the detective, Lohmann. But he doesn’t come in for 25 minutes. He does have the largest amount of screen time, but by no means does he dominate, and we certainly aren’t concerned—.” He goes on in a confiding tone. “I heard one time a very scary thing, and I think it’s not going to happen, but who knows: that they’re going to remake this with Arnold Schwarzenegger as the detective.” The students laugh and groan. “I can assure you that if they did that … we would see about [Schwarzenegger’s] family, his internal conflicts. Notice what we know about Lohmann, other than some personality quirks, is all about his job and how he carries it out. He isn’t, again, a main character in the way that most films would develop it.”

The main character is in fact “something like the city,” Gunning says—a departure from traditional cinematic dramaturgy. Lang eschews the establishing shots, timely close-ups, and other tactics that continuity editing uses to unfold a scene’s psychological and dramatic logic. By contrast, It Happened One Night offers a sense of access to its characters’ emotions. Capra’s Oscar-sweeping movie, Gunning says, is “a perfect combination of something I think is brilliant, but very much within the Hollywood rules”—specifically the continuity rule.

He puts up an early scene. Her bus delayed overnight by a storm, Colbert’s runaway heiress stands on the street in the rain. Gable, a desperate reporter looking for a career-saving scoop, wants her to take shelter in a nearby room he’s rented. “They’re still not friendly with each other,” Gunning says. “The work of this film is to make these two initially unlikely seeming people from different classes, different worlds of experience … fall in love with each other, and make us believe that and see it happen. It’s a good task.”

Inside the motel room, Colbert looks at Gable uncertainly. Gunning hits pause. “Now, one of the main things that holds shots together … in the classic Hollywood system, is the look. So we saw her look off. We immediately wonder, what’s she looking at? Answered by the next shot. Notice how the cuts are spliced together. They’re joined by satisfying a curiosity.” The kind of curiosity Lang likes to frustrate. “So what’s she looking at? She’s looking at Clark Gable. What’s he doing?”

Hanging a propriety-preserving blanket between the room’s two beds, for one, and calling it the Walls of Jericho. “He’s raised this issue of, basically, sexuality, right? And division,” Gunning says. “Partly it’s saying, we’re not going to do it. But it’s also saying, will we do it?” He walks the class through the rest of the famous scene, showing how the sequence of camera shots tracks the characters’ slow dance of advance and rebuff.

Close-ups tell the viewer when emotions are running high. As Gable turns down one of the beds for her, the camera zooms in and lingers on Colbert’s face. Later when Colbert, undressing behind the Walls, throws a stocking over their top, the lens rests on Gable’s face. Meanwhile, continuity editing conventions like the 180-degree rule ensure we’re not disoriented spatially by the close-ups. (The rule dictates that the camera hew to one side of an imaginary line drawn between the two characters; the same principle is essential to filming a football game.) And near the scene’s end, the camera does something unexpected: it leaves the blanket out of the frame.

With the Walls of Jericho elided, shots of Gable looking to his right and Colbert looking to her left—we know they’re looking toward each other because of establishing shots and the 180-degree rule—make the two seem to occupy the same space. Even the same furniture. “We’re definitely being told to figure out that by the end of this film, they’re in bed together,” Gunning says. “And married.”

With the light turned out, the characters are dramatically backlit. “Suddenly a new degree of romanticism is introduced. ... It’s a love scene! Made by the 180-degree rule. The forbidden moment of them getting into bed together is given to us.” Then Colbert breaks the spell: “By the way, what’s your name?” No longer in close-up when the camera returns to her after Gable answers, “she’s removed herself from intimacy, or at least the camera has. But he’s still—smoking.” After one last shot of Colbert, eyes lit, the camera pans all the way out again. “They get us out of it,” Gunning says. “Reestablishing shot.” And scene.

Syllabus

What is cinema? That’s the underlying question of every course Tom Gunning teaches. It’s also the English title of this course’s main text, Qu'est-ce que le cinéma, a two-volume collection of essays by the French film theorist André Bazin (Gunning assigned the 2005 University of California Press translation). Required reading also includes Robert Bresson’s Notes on Cinematography (Urizen Books, 1977) and a dozen articles. The reading load is modest but Bazin, Gunning says, “is a little bit like those toys you had as a kid that you put in the water and they expand.”

Monday night screenings round out the syllabus. The 19 films hail from the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and India. Students may be tempted to watch them on DVD, but Gunning advises those who don’t plan to attend the screenings to drop the course—“the experience of seeing them larger than life, on the big screen, is essential.”