Cubism, a light-painting photograph. (Photography by Jason D. Page)

Exploring the attributes of low light, an architect and a physicist try to cultivate a dim awareness.

You could feel the room shift as soon as the lights went dim. It was the middle of fall quarter, and in a basement classroom of the Logan Center for the Arts, Sidney Nagel was starting off his students’ morning in a shroud of not-quite-total darkness. All fall, in teams of three or four, they’d been working on projects—an installation, an image, a device—meant to explore the particular qualities of low light. This was the class’s only assignment, and Nagel worried that the students might be getting caught up more in the idea of light itself: their works in progress so far showed more sunshine than moonlight. “Everyone seems a little bit unsure of what you’re supposed to be experiencing,” Nagel said, heading for the light switch. “If I say low light, what’s the first thing that comes to mind?” The room went dark.

There was a murmur, and then a pause. “It’s more intimate,” offered one student. “Quiet,” said another. Someone mentioned feeling solemn, another relaxed. Another felt uncertain, his words suddenly seeming “less true,” his surroundings less concrete. For half an hour, students tossed out thoughts and observations, sometimes almost whispering as they spiraled deeper into the question of light within darkness: the gloom and stillness of winter, the beauty and impermanence of twilight. Even shadows, one woman said, are “there and moving and gone.” Nagel noted the graceful ephemerality of leafless trees silhouetted against a low-lit, heavy sky. Recalling certain rare daybreaks back home in LA and the particular slant of Chicago’s fall sunsets, one student concluded, “There’s this magical thing that happens when the sun sinks low and sneaks into our lives, almost.”

“OK,” Nagel said a few minutes later, as the classroom fell back into silence. “So these are things we’d like to see you struggle and experiment with.”

For Nagel and his coteacher, James Carpenter, the class itself was an experiment. And, not unintentionally, a bit of a struggle too. The Interaction of Light and Matter: Art and Science was listed in the course catalog under physics and the arts, drawing students from both and neither. It was part of a yearlong collaboration, sponsored by the University’s Gray Center for Arts and Inquiry, between Nagel, a physicist and Chicago professor, and Carpenter, an artist and architect from New York. The two have been friends for several years, ever since Carpenter, by an odd coincidence, got invited to speak at a conference marking Nagel’s 60th birthday. His presentation offered a description of his design work, which is based in light. For Carpenter, light—its shape and scope, its abundance or scarcity, its clarity or cloudiness—can be worked and honed and put to use almost like any other building material. His birthday talk was called “The Structure of Transparency.”“Absolutely splendid title,” Nagel says. “The whole thing blew me away.”

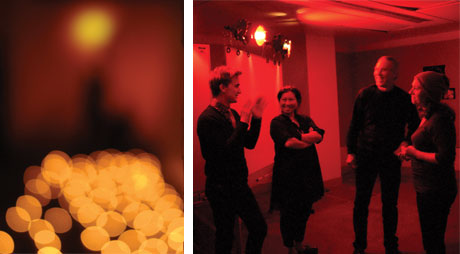

Using candles, smoke, and LEDs, students in Nagel and Carpenter’s class created installations exploring low light. (Photography by Kartik Prabhu)

From the beginning, their collaboration pushed the scientist and the artist into an uneasy exploration of territory neither quite knew how to navigate. But in a way, it seems only natural that Nagel and Carpenter would wind up working together. For one thing, each has a toe in the other’s field: with a background in chemistry and biology, Carpenter creates artwork with a scientific disposition, using mirrors and prisms and lenses to manipulate sunlight and atmospheric effects. “The best visitor in my lab we’ve ever had,” Nagel says. “He asked the best questions.” Nagel, meanwhile, finds himself drawn to the beauty and elegance of physical phenomena. His black-and-white photographs of falling glycerol droplets and oil-and-water emulsions cover the walls of his office, and some are in the Smart Museum’s permanent collection. “I want to make sure that what I do is important to the physics, but if I can bring out the aesthetic beauty of it, that’s equally important to me,” he says. “It’s part of what makes me human.”

Both men have also centered their professional lives around the close observation of everyday events, mining new meaning from experiences the rest of us take for granted. “Many complex phenomena are so familiar that we hardly realize that they defy our normal intuition,” reads the homepage of Nagel’s laboratory website. An experimental condensed-matter physicist, he studies the “cascade of structure” contained in the drizzles from a spoonful of honey, the molecular disarray concealed in a pane of glass, how droplets form and fall and splash, and why sand sometimes flows like liquid.

For two whole years Nagel stared at coffee stains, trying to figure out why spills dry with a dark ring around the edge. Shouldn’t they evaporate more evenly, he wondered, or with the darkest spot in the center? And yet, every liquid Nagel tried—milk, blood, ink, paint, oil, alcohol—dried this same way, with an emptied-out center and a thick, dark edge. “This is a piece of nature that is confronting us every single day,” he told his students the first week of class. In a simple observation, he had found “a new piece of physics.”

If Nagel’s work looks at the everyday and asks why, Carpenter’s looks at it and asks what else might be seen there. “There’s this huge wealth of information that’s always in front of us,” he says, and people only perceive the narrowest sliver of it. In his work he tries to capture and “re-present” what often lies just beyond our attention: a leaf, a sky, a shadow, a splinter of light. For a 1978 film installation called Migration, Carpenter set up cameras along a small river flowing into Puget Sound and recorded the movement of salmon from one camera to the next. Projecting the whole film onto a gallery floor, he slowed down the speed, holding the images a little longer. “As soon as you do that, you see that the same piece of film has another layer of information in it,” Carpenter told an audience at the School of the Art Institute during a talk he and Nagel gave in October. “You realize after a few moments that you’re also looking at a perfect reflection of the sky overhead.”

Carpenter’s projects often prompt that kind of realization, the sudden awareness of something visible but unseen. In college he studied architecture and sculpture, emerging with a degree in the latter, but his true fixation was the study of light and how it defines the experience of place. With his firm, James Carpenter Design Associates, he constructed a window for a seminary chapel in Indianapolis that casts silhouettes from the landscape outside—clouds, trees, birds in flight—onto an interior wall; bars of light, shifting as the sun moves from one horizon to the other, shimmer across the chapel’s cross. For a private home in Minneapolis, Carpenter transformed a window looking out on a neighbor’s fence into a “periscope” that collects its view instead from the sky and the canopy of a nearby tree. Designing the outer envelope for Seven World Trade Center, the first building to go up at Ground Zero, Carpenter embedded stainless steel prisms in the surface to attract light that wouldn’t otherwise reach the densely surrounded building, drawing it out of the shadows.

Carpenter also designed the three Midway crossings to light pedestrians’ paths between the north and south ends of campus. As the sun sets, tall masts of LED illumination gleam upward from widened sidewalks. The “light bridges,” as they’re commonly called, evoke Edward Law Olmsted’s 1871 plans, never realized, that envisioned the Midway as a Venetian canal connecting the lagoons of Jackson and Washington Parks. At night, the bridges seem almost to be floating above a dark sea.

Carpenter designed the skin of Seven World Trade Center to attract and reflect light in its dense neighborhood. (James Carpenter Design Associates)

Nagel and Carpenter’s collaboration is one of several under way or upcoming between artists and academics—a choreographer and a group of music PhDs, a filmmaker and a film historian—sponsored by the Gray Center, an initiative launched in 2011 to expand the pursuit of the arts on campus. Like the Logan Center, the Gray Center emerged in part as a response to a 2001 report on the future of the arts at Chicago. As Gray Center director David Levin puts it, the report “noted that historically at the University, the arts had been marginalized, not just to their discredit, but to the University’s discredit.” Largely, the arts were considered “something that was unnecessary and a distraction from the real task at hand, which was taken to be intellectual scholarship. And I think a number of us on the faculty,” says Levin, who teaches in Germanic studies and cinema and media studies, “felt that art was not marginal to our work, but absolutely essential.” Part of the Gray Center’s purpose is to bear out that claim, to show that “transformative, experimental thinking” takes place between scholars and artists. Levin calls Nagel’s collaboration with Carpenter an “encapsulation” of the center’s project: a partnership between two accomplished professionals that is “unfamiliar and risky” for both. “That’s fundamentally the charge of the Gray Center,” Levin says, “to bring about collaborations that are scary for both parties.”

Beyond that, the rules are minimal. Jettisoning what Levin calls the “bottom-line pressure” to produce a performance or publication or conference, the Gray Center doesn’t require its collaborators to come up with any of those things, though many of them have and will. “We felt that collaborations like the one between Sid and Jamie don’t operate at their best when they’re under pressure to produce,” Levin says. “I really don’t know what they will produce, and I don’t want to force that question prematurely. They have interests that they share, and where that takes them is the job of the collaboration.”

The first place it took them was to Greenland. In December 2011, around the time of the winter solstice, the darkest period of the year, Nagel and Carpenter spent four days in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital city. Carpenter was there to research a future project; an admirer of winter’s gray, Nagel came along for the exploration. “To look at light when there wasn’t much of it,” Nagel says. There was never much of it—and what there was was mostly gray. Daybreak came at around 10:30 a.m. each day, and within four hours the sky was dark again. They tromped through snowdrifts and watched the sun tilt along its tiny arc at the base of the horizon. At night they could see slabs of ice slipping out to sea in the darkness beyond the fjords. Nagel noticed that the light seemed more polarized than in Chicago. Carpenter noticed that the sky seemed brighter up toward the North Pole. “Which you would assume would be darkness,” he says.

One day, the two of them borrowed a car and toured around the city, to explore the light from different angles. “The people said, ‘Here’s a car; you won’t get lost,’” Nagel recalls. “And that’s absolutely true, because there’s no way of getting outside of Nuuk.” All the roads turn back on themselves. “You can’t go from Nuuk to someplace else,” he says; beyond the city it’s ice and wilderness. Another day, they hiked up a hill away from town and took a photograph that Nagel is still trying to figure out. It’s a picture of a hole in the snow. “We put the tripod leg into the snow this deep,” Nagel says, holding his fingers a couple of inches apart, “and then we look in, and it”—the snow—“is absolutely blue. Nuts. Pale blue. And it was unmistakable.”

“Yes, it wasn’t subtle,” chimes Carpenter.

“No, it wasn’t a subtle effect.”

“Totally blue.”

But why? Nagel doesn’t know. “Well, water is blue,” he says. “This is what we’re told.” And to some extent that’s true. “Water is slightly blue. It absorbs a little bit of red, because of the vibrations in water and the infrared, ... and what comes back is more blue,” Nagel says, unspooling. “But I can look through a glass of water that same thickness and it’s not blue.” He believes something else must be going on. “There’s also this thing,” Carpenter offers, “that there’s more blue light available at that high latitude.” On the southwestern coast of Greenland, Nuuk is just 150 miles from the Arctic Circle. Nagel notes that the underbellies of glaciers are deep blue, but adds that that’s partly a function of intense compression. “It’s a mystery.”

By the time Nagel and Carpenter arrived home, the idea for the class was starting to take shape: a course exploring the physics and aesthetics of low light, especially natural light. They’d ask students to make close observations, to pay attention to their senses and perceptions. And they’d teach it in the receding light of fall.

The tall silver masts of Carpenter’s pedestrian “light bridges” on the Midway glow as the sun sets. (Photography by Tom Rossiter)

“None of you should be inside your comfort zone right now,” Nagel said, calling the class to order on the first day. “The scientists should be trying to think in terms of the art, and the artists should be trying to think in terms of the science. This is not easy.” About 20 people signed up for the course—MFA students, physics PhD students, undergrads studying science, math, art, English, psychology, public policy—none of them quite knowing what to expect. Week after week, while Carpenter and Nagel offered lessons on refraction, interference, polarization, and the behavior of what Carpenter calls “volumetric light,” interdisciplinary teams of students toiled away on their final projects. They experimented with candlelight, underwater illumination, LEDs, infrared light, sodium lights, and smoke. Nagel and Carpenter kept urging them to dig deeper, to loosen their imaginations and hone their observations, to move beyond science projects and artistic concepts.

As the quarter wound past midterms, Nagel asked students a question he and Carpenter had been asking themselves for almost a year, and for which they had not yet found an answer: had they found common ground? Was there any? For some the answer was yes. Science and art are both extensions of philosophy, one student said, of human attempts to answer the oldest questions, to discover something new about the world—and report back. To one physics graduate student, an arts-major classmate describing his improvisation with a paint canvas sounded very much like a scientist in the lab. “Scientists also improvise,” he said. “They brainstorm, they stumble around, they make inspired leaps that have no rationale in the beginning.”

Others, though, had struggled. Science students found themselves sometimes mere engineers of their arts classmates’ brainstorms; artists found themselves intimidated by the enormous complexity of the science. “We catch ourselves talking past each other,” said one physics PhD student of his teammate, a scupltor. A film MFA student said he and his team had found difficulty in “moving beyond phenomena and taking that next step” into art. “That whole process of thinking and rethinking is interesting. And kind of a struggle.” There was real frustration in their voices, and real effort. You could sense them reaching beyond themselves, leaving the comfort of their expertise. “There’s no clear path,” someone said.

Perhaps not, but there is always the journey ahead, the exploration. “Some of you talk about science as this certain process,” Carpenter, who’d been listening to the discussion, finally said. “I think it’s closer to art, where you’re trying to arrive at an understanding, the exploration of a concept.” In both, “there are many, many false starts, and then eventually ... you cast away your immediate ideas and arrive at something that’s more coherent—a solution, a resolution.” The light.