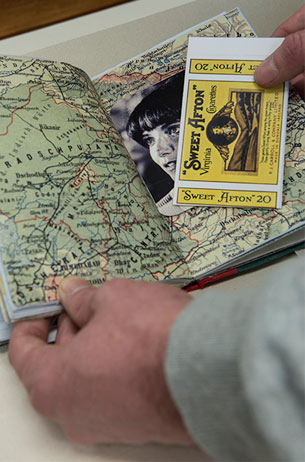

Above: The mysterious package; below: inside the journal. (Photography by Robert Kozloff)

A fake journal goes on display in a real museum.

In December, the College Admissions Office received a mysterious package addressed to Henry Walton Jones Jr. (AB’22)—aka Indiana Jones. The news captured the world’s attention. Packed inside were a handwritten journal attributed to Indy’s mentor, Abner Ravenwood; worn period letters and notes; and pictures of actress Karen Allen, who played Jones’s love interest Marion Ravenwood in the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The Admissions Office’s announcement of the mystery package attracted widespread curiosity, in a way that no other fictional alum could. Theories abounded. An unorthodox admissions essay? (There was no application inside.) Viral marketing for an upcoming Indiana Jones sequel? (Not so, said the filmmakers.) A plea for help from a parallel universe where Indiana Jones was real? (Highly unlikely, but a man can hope.) More than one person accused yours truly of being the envelope’s creator, though I sniffed I never would have misspelled “Illinois” on the label.

Closer examination raised more questions. How did the package make it through the postal system with fake Egyptian stamps? Why was the “journal” not handwritten? (Some words were misspelled in ways that would be odd to make when writing, like “hat” for “that.”) Why was there an item marked “Rick’s Cafe Americain,” suggesting a different movie altogether? Why address the package to Indiana Jones but send it not to the fictional college where he taught but to his alma mater? And the one Indiana Jones movie that prominently featured a journal was not Raiders but Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade—why not base the package on that film?

Within a few days, the mundane truth was revealed: one Paul Charfauros, of Guam, made the replica movie prop for a collector in Italy. While passing through the mail from Charfauros’s home through Hawaii, the inner package separated from its envelope; the friendly people at the USPS used the address on the fake package, added a zip code for Chicago, and sent it on its way. After the mystery was solved, Charfauros donated the wayward collectible to the University.

That’s where the Oriental Institute comes in. Even before its provenance was established, OI museum chief curator Jack Green made the case that the materials belong in a musuem. “Maybe it contains information our scholars need,” he said at the time, tongue planted firmly in cheek. Admissions obliged, and Green and Gil Stein, the OI’s director, arranged to display the materials in the building’s lobby, with as much curatorial care as a Nubian statue. They’ll be there until March 31, says Green, and then be retired to the OI’s archives.

“For all of us at the OI, the Indiana Jones series has been an inspiration and a curse,” says Stein. The movies are nothing like real archaeology—among other things, the danger of having your face melted by an artifact has been way overstated. But they’ve also encouraged an entire generation of scholars to enter the field. And as the display notes, Jones might well be based on two real Chicago archaeologists: Egyptologist James Henry Breasted, who founded the OI in 1919, and Robert Braidwood, PhD’43, who studied the Near East. (The Indiana Jones display is tucked under a watchful bust of Breasted.)

Green says the display, dubbed “Raiders of the Lost Journal,” fits into the museum’s mission to make the past relevant to the people of today but admits “it’s a bit of fun, really.” Looking upon the faux letters and pictures in the display case, it strikes me that the exhibit is the most U of C response possible—a completely serious embrace of absurdity. I like to think my fellow alumnus Indy would approve.