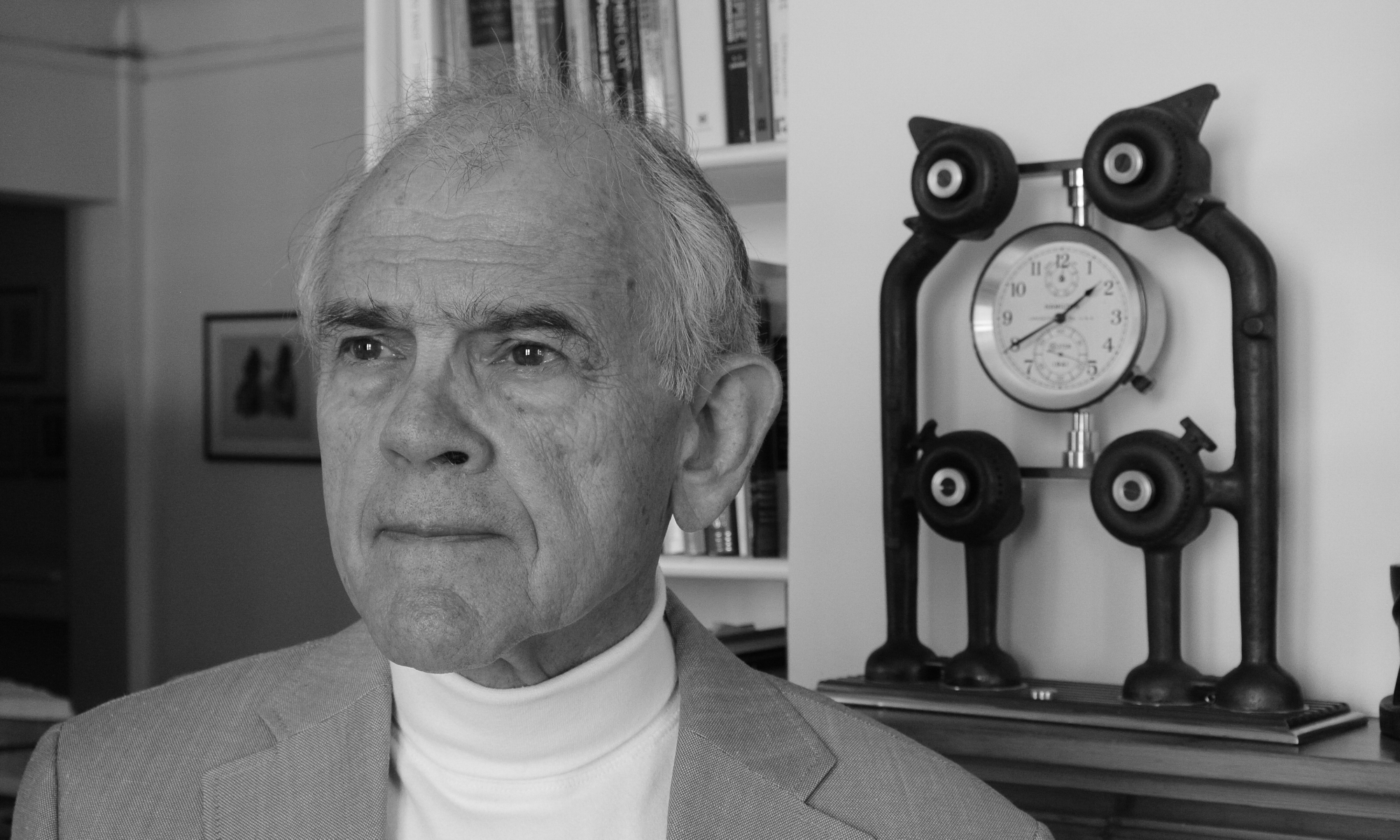

John Snyder with his stove burner chronometer in the background. (Photo courtesy John Snyder, AB’56)

John Snyder, AB’56, gives new life to the lost and discarded.

In 1943, when John Snyder, AB’56, was eight years old, his father bought a 1,000-acre farm outside Walhalla, South Carolina, in the elbow crook between the Carolinas and Georgia. Behind the main house was an outbuilding where his father kept tools; he called it “the warehouse.” Its walls were lined with open bins that gradually filled with cast-off bits—washers, rope, wire, rusty hinges—found in the woods or on the side of the road.

“I would watch Daddy, a broken part in one hand, pillaging through the bins until he finally plucked out an object that recommended itself,” writes Snyder in an essay about his young life published on his website. “Like magic, pieces always seemed to come together whether repairing or making something from scratch.” His father was a finder and a fixer; John, a maker in the making.

He recalls from the warehouse a wooden frame from a McClellan saddle, standard issue for United States cavalry, that was used in the American Civil War. It had no leather, but his father had received a goatskin in exchange for a bale of hay. Snyder identifies the resulting goat-upholstered saddle as the spark for his own bin-keeping and collecting of materials from salvage yards, sidewalks, and railbeds. You never know what might be discovered, he says, or how it might be useful.

Taking after his father—a farmer, builder, inventor, painter, and poet—Snyder has had a miscellaneous collection of careers. After graduating from UChicago, he served in the navy (he trained as a pilot, but budget cuts prevented him from earning his wings); bought glass and china for Bloomingdale’s; and conducted research and development for a carpet manufacturer, acquiring several patents—a testament to his ability to fabricate solutions to technical problems. In 2001 he retired as an executive director after two decades at Morgan Stanley. He’s also written off-Broadway plays in addition to his memoir, Hill of Beans: Coming of Age in the Last Days of the Old South (Smith/Kerr, 2011).

All the while, Snyder was building and sculpting with his found fodder, melding utility with art. As materials recommended themselves to his father, they reveal themselves to him. For a recent exhibit, titled Bins of Miscellany in honor of his father’s Walhalla warehouse and his own collections, he writes that his work is inspired by the “remarkable beauty of mechanical things often shrouded from view in the interior of machinery, instruments, and appliances of everyday life.” His materials are found in “places where spent things are discarded.”

Yet not all of the raw materials Snyder uses are common detritus. You don’t often stumble upon centrifuge parts (Centrifuge with Twin Spiral Accelerators, 2013) or a prism from a World War II tank gunsight (Asteroid Station, 2016) while strolling down a dirt path. He sources components from a friend who owns a professional kitchen outfitter, for instance, or purveyors of military surplus, or Snyder’s version of paradise: a place called Vulcan Scrap Metal Co. in Stamford, Connecticut.

Vulcan sells metal of every shape you can imagine, he says. He found the whole nozzle for Firehose Nozzle Lamp, 2002, in the bronze section. These pieces have no meaning to Vulcan’s vendors, says Snyder; they sell by the pound. But he sees beauty in the scrap, and future purpose. To enter, “you went under a World War II bomb, a practice bomb, they had hung over the gate that said, ‘Have a blast at Vulcan,’” he recalls. “Eventually I bought the bomb from them, too.”

Snyder continues to create art in his New York and North Carolina homes, with lathes and milling machines, and the windowsills, floors, and closets filled with his trove, destined for reinvention.

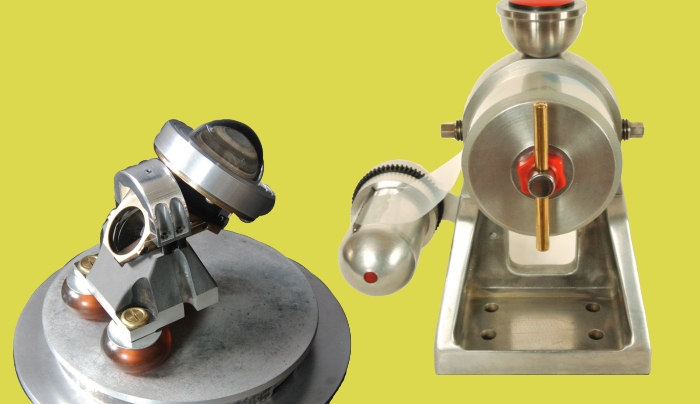

Centrifuge with Twin Spiral Accelerators, 2013

Stainless steel, bronze, aluminum, rubber

W 9" x L 15" x H 10"

Snyder found what he thought was a stainless-steel centrifuge and fitted it with stainless-steel accelerators (spiral-shaped pieces), capped with a stainless-steel ball stamped with the camera company name Leica. He doesn’t know their original purpose, but he has a bucketful. “Because I have so many,” he says, “they probably didn’t have a good use for them. They ended up in the paws of people like me.”

Firehose Nozzle Lamp, 2002

Bronze, aluminum, stainless steel

H 27" x W 14" x diameter of base 9"

This functional lamp was built around a bronze firehose nozzle discovered at Vulcan Scrap Metal Co. The base is made from an industrial liquid stirrer, and the shade is a stainless steel funnel with a ribbed aluminum skirt, both perforated for cooling.

Fire Hydrant Towel Dispenser, 2006

Aluminum, brass, bronze, cast-iron base from NYC fire hydrant

H 16 1/2" x 7" base and 4 1/2" top diameter

Snyder's wife, Virginia Lawrence, commissioned a paper towel dispenser heavy enough to stay put. A cast-iron NYC fire hydrant cover that she “found” on the street provides stability. A spring-loaded bronze gear presses down to anchor the roll before tearing off a sheet. The little bronze ball is swivel-mounted on the base so that it falls by gravity into the paper towel roll and keeps it snug as the diameter of the roll decreases.

Asteroid Station, 2016

Aluminum, glass, polyurethane, stainless steel, bronze

H 9" x 10" diameter

Snyder envisions this piece as a survey station deposited on an asteroid. Its landing might have been cushioned by the three rollerblade wheels. Its core contains a brass mounted prism from a World War II tank gunsight. The apparatus is mounted on circular aluminum disks, pocked by imagined collisions with high velocity—possibly interstellar—particles.

Tape Dispenser, 2014

Aluminum, stainless steel, brass, polymer

H 8 1/2" x W 9" x D 6"

Snyder and his wife use copious amounts of tape, and his collection contains several functional dispensers. (“I make a lot of tape dispensers because I like to make things that work.”) Virginia custom ordered a heavy dispenser for her preferred two-inch rolls. The resulting sculpture weighs nearly seven pounds.