Workers at the Bohemian Women’s Publishing Company. (Bohemian Women’s Publishing Company records, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago)

An exhibition at the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center highlights women’s contributions to the craft of printing.

Peruse the shelves of any bookstore or library and you are almost certain to find a book set in Baskerville—a typeface that bears the name of its creator, the 18th-century printer John Baskerville. Baskerville’s contributions to the history of the printed word are widely celebrated; his 1763 edition of the Bible is considered a masterpiece. Far less well known is the woman who became his wife, Sarah Eaves, who worked behind the scenes in a variety of ways, including casting type—that is, creating the individual metal letters that would be used on Baskerville’s press.

Stories of women like Eaves are present all throughout a new exhibition at the Special Collections Research Center, A Pressing Call: Five Centuries of Women Printing, which runs through April 18. The exhibition was cocurated by Special Collections metadata librarian Rebecca Flore, PhD’21, and rare books curator Elizabeth Frengel.

A Pressing Call highlights the many ways women have contributed to an industry whose most famous figures—Johannes Gutenberg,

Aldus Manutius, William Caxton—are men. But women were always present, casting and setting type, feeding paper into presses, proofreading, and more. They also served as publishers and booksellers, functions that were historically less distinct from printing than they are today. Many, including Eaves, married into the business and carried it on after their husbands died.

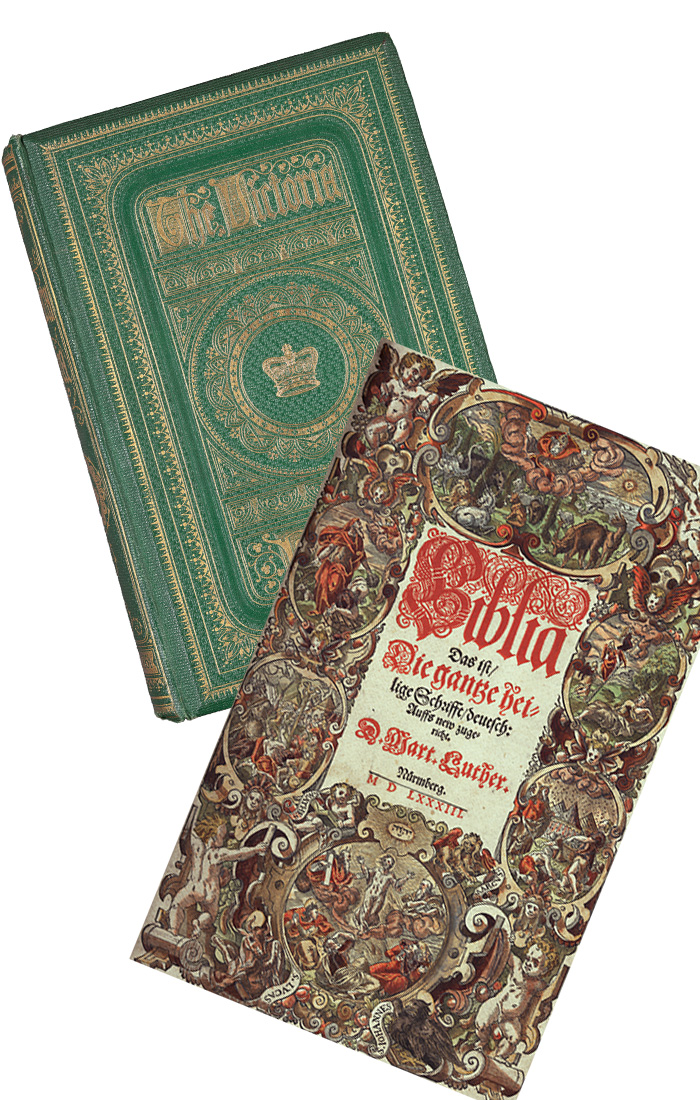

The exhibition highlights treasures from the library’s collection, including a richly illustrated 16th-century Bible from the German printer Katharina Gerlach, a volume of poetry and prose from the 19th-century English women’s rights activist and publisher Emily Faithfull, and a book typeset and bound by Virginia Woolf. (In the early days of Hogarth Press, founded by Virginia and Leonard Woolf, the couple purchased a small handpress, which they kept in their dining room. The book on view in the exhibition, like many of the Woolfs’ early efforts, is “really scrappy looking,” Flore says—clearly the work of novices.)

Together, these objects and the others included in A Pressing Call reveal that printing was, in fact, women’s work from its earliest days—regardless of whose name appeared on the title page.