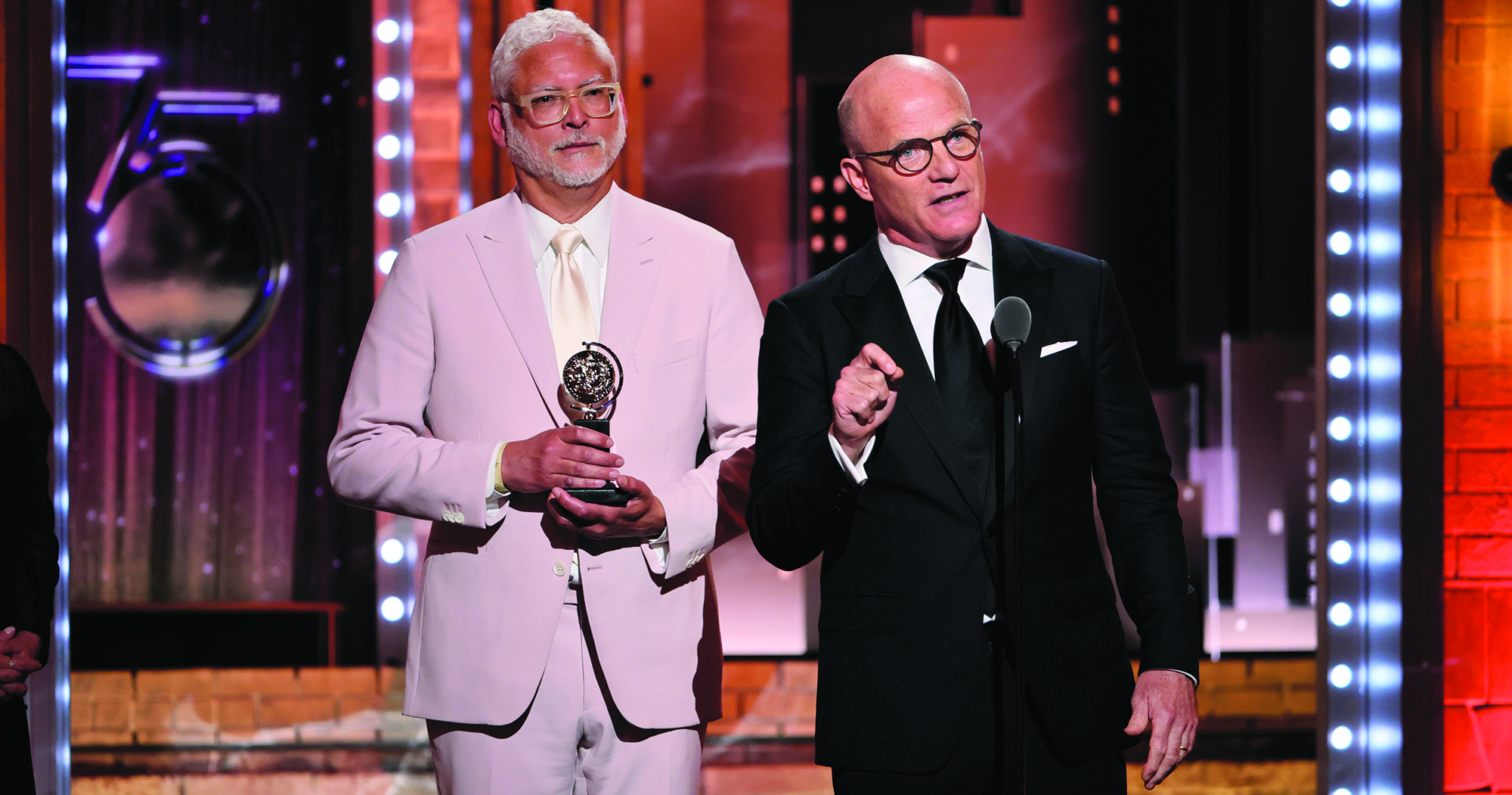

On June 12 at Radio City Music Hall, Court Theatre’s Marilyn F. Vitale Artistic Director Charles Newell (right) and executive director Angel Ysaguirre accepted the 2022 Regional Theatre Tony Award. (Photo by Theo Wargo/Getty Images for Tony Awards Productions)

Court Theatre brings home a Tony.

In June Court Theatre’s Charles Newell took the stage at Radio City Music Hall in New York City to receive the 2022 Regional Theatre Tony Award. In a crisp black suit and matching tie, he addressed the Broadway League and the American Theatre Wing, which had bestowed the prestigious honor. “Thank you for seeing us so clearly,” said Newell, the Marilyn F. Vitale Artistic Director, who has been at Court for almost 30 years.

Only one nonprofit company receives the coveted honor, which includes a $25,000 grant, each year. Court was recognized for its sustained artistic achievement, contributions nationally in presenting classic theater works, and its commitment to Black theater. The honor was a long time coming—there was the moment 16 years ago when the Wall Street Journal deemed Court “the most consistently excellent theater company in America”; there was the 2019 New York Times feature highlighting its adaptation of The Adventures of Augie March.

Those “national pings,” Newell says, have been a shot in the arm, but mostly he and colleagues have kept their eyes on the work in front of them, never dreaming they’d win a Tony. (“I can authentically and honestly say it was the last thing I thought would ever happen.”) From its unique vantage point at the University of Chicago and on the city’s South Side, Court has critically reexamined the classical canon, adding new works and new voices that expand the definition of what constitutes a classic while fostering closer relationships with the artists and audiences of its surrounding neighborhoods. “Name another research university that is producing as much cutting-edge, field-leading research,” Newell says. “Name another community in the United States that has generated more cultural riches.”

Court Theatre got its start—and its name—in 1955 as an outdoor summer theater whose productions took place in Hutchinson Courtyard with actors drawn largely from the Hyde Park community. By 1971 UChicago classics professor D. Nicholas Rudall, a translator of ancient Greek tragedies, took the reins as artistic director and turned Court into a professional University-based company focused on classic texts. A decade later, Court got its own ivy-covered home at Ellis Avenue and 55th Street, housing an intimate 251-seat theater space.

Enter Charlie Newell, who joined Court in 1993 and assumed artistic leadership the following year. He has since directed more than 50 productions, won an Artistic Achievement Award from the League of Chicago Theatres and four Joseph Jefferson Awards (Chicago’s top theater honor), and been named “one of the city’s most significant artistic assets” by the Chicago Tribune.

During Newell’s tenure, Court became the official Center for Classic Theatre at the University of Chicago, partnering with faculty members who enrich its dramaturgy and inform the company’s new and more equitable vision of classic theater. “We’ve been on a decades-long journey about expanding—about challenging—the question of what is classic,” Newell says. “What are the stories that are not being told, and why? What are the voices that have been shut out?”

Court has taken major strides toward achieving what Newell calls “canonical justice.” A pivotal moment came in 2005 when he invited acclaimed director Ron OJ Parson (now a Court resident artist) to direct August Wilson’s American Century Cycle, a set of 10 plays exploring the 20th-century experience of Black people in America. Since then Court has staged adaptations of classics like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Richard Wright’s Native Son; unearthed rarely produced plays by artists of color; and commissioned new works by Black playwrights. Court’s casting has made similar advances; two-thirds of its actors are artists of color—most from Chicago and many from the South Side.

The changes are accompanied by a relationship with local communities that is unprecedented in the theater’s history, Newell says. Take, for example, the Civic Actor Studio, a four-day retreat for South Side community leaders that uses theater exercises and texts to help participants harness their creativity and power. CAS alumni “have become partners of the theater,” says Court’s executive director Angel Ysaguirre, who joined in 2018. “It’s just what happens when you’re in closer relationship with people—you know them better and they know you better.” For Gabrielle Randle-Bent, who cofounded CAS and joined Court as associate artistic director this summer, these kinds of outreach efforts aren’t ancillary—they are central to the company’s mission. Community engagement, she says, “is an artistic pursuit.”

Now it’s an artistic pursuit they get to undertake with a Tony in hand. For Newell, the award represents “a glorious singular moment in the theater’s history,” but he’s already focused on the future. On the night of the Tony Awards ceremony in New York, far from the red carpet and designer couture, August Wilson’s Two Trains Running—the ninth of 10 plays in the American Century Cycle—wrapped up its monthlong run. Court hopes to complete the cycle with a production of Joe Turner’s Come and Gone in an upcoming season. They’re also preparing to workshop a newly commissioned play by Nambi E. Kelley about the life of Stokely Carmichael. That’s the work, Newell says: “What’s the art we’re going to do next, and next, and beyond?”