As book bans spread nationwide, a professor, an author, and UChicago’s library system defend the freedom to read.

The course is named, rather provocatively, Reading as a Writer: Obscenities.

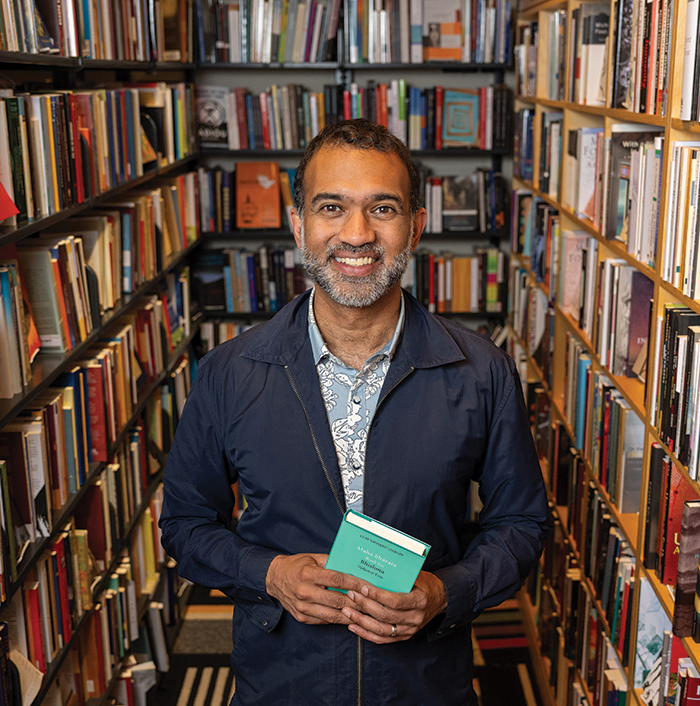

Obscenities (for short) is a creative writing course taught by poet Srikanth “Chicu” Reddy, professor of English language and literature. It meets in Midway Studios, where Lorado Taft once made his massive sculptures. The classroom has a high, slanted ceiling with multiple skylights and, on one wall, a large brick fireplace that doesn’t work.

It’s week five of Winter Quarter. The students have read Molly Bloom’s stream-of-consciousness soliloquy from Ulysses, love poems by Sappho, and Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” so far.

They’ve also read, for historical context, Dirty Works: Obscenity on Trial in America’s First Sexual Revolution (Stanford University Press, 2021). The “civil libertarian commitment to free expression” emerged in the late 1920s and the 1930s, cultural historian Brett Gary writes. Before that, the United States was a nation of obscenity laws and vice squads; the 1873 Comstock Act made it a crime to circulate materials deemed obscene.

The assigned text this week is “The Lottery,” the 1948 short story by Shirley Jackson. This throws me a little. “The Lottery” is obscene? Am I forgetting something from eighth grade?

I am not. The story, about a New England village that ritualistically stones one of its citizens to death every year, is seared into my memory. But Reddy’s syllabus defines obscenity very broadly: “A term for what is repulsive, abhorrent, excessive, or taboo in a society.” Judging by the deluge of negative letters The New Yorker received after “The Lottery” was published—many readers confused it with reportage, he explains—his standard for obscenity was met.

“I don’t think The New Yorker wanted to spark a debate about censorship,” unlike other publishers who deliberately wanted to push against censorship laws, Reddy says. The New Yorker is “known for being belletristic,” not revolutionary.

Nonetheless, the assigned readings also include two articles from the 1980s about attempts to stop “The Lottery” from being taught in schools. This is typical of book bans today, which usually happen at the local level—but that’s changing. Some states, such as Utah, have passed laws banning certain books from schools statewide. More recently, book bans reached the federal level: In April the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, under orders from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s office, removed 381 works from its library.

Many of Reddy’s students have read “The Lottery” before. But to a generation that grew up reading or watching Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games series—which has a similar premise, though I’d never thought of it that way before—Jackson’s story has lost its ability to shock. “I think I knew where it was going,” says one student. “A lottery … OK, someone’s going to die.”

When the story first came out, it was “probably inventive,” the student says later in the discussion, “but now I’ve seen it so many times, it felt very basic.”

“What’s violent about ‘The Lottery’?” Reddy asks. “What is so upsetting?” The discussion circles around the notion of the banality of evil, the biblical connotations of stoning, censorship in the 1980s.

“I’ve had, let’s call it, the unique displeasure of actually attending some of these meetings where banned books are being discussed,” a student says. He went to high school in Texas, and his school’s librarian had asked him, as a UChicago student, to speak at a school board meeting. “I wouldn’t suggest it,” he says, with a tinge of bitterness. “They’re usually not very productive.” The board ended up adopting more restrictive policies.

The class discussion shifts to the artistry of the story—the choices Jackson is making as an author. A student reads the first paragraph aloud: “The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day; the flowers were blossoming profusely and the grass was richly green.”

“It’s almost aggressive,” another student points out, “how nice this June day is.”

“It’s actually kind of almost bad writing,” Reddy says. “Deliberately kind of stock, cheesy, sentimental Americana.”

Reddy and the students pick through the story carefully, like they’re examining a crime scene. The unnamed narrator uses expressions like “of course,” Reddy observes: “The children assembled first, of course.”

“Of course,” he says, a phrase that assumes something of the reader: familiarity. “We’re ‘in’ on the lottery.”

But while readers may be “in” on the lottery, we’re not invested in the well-being of any particular villager. “If Tessie Hutchinson”—the lottery’s eventual stonee—“felt like a fully realized character who we cared a lot about, like Katniss Everdeen [the protagonist of The Hunger Games], we would feel outrage,” Reddy says. “Instead we have a distance from her.” It’s a social drama, not an individual one.

When writing your own fiction, Reddy advises the students, that’s an important thing to consider: when to “go close,” he says, and when to “maintain the distance.”

Another student then reads aloud the final, chilling phrase of the story, “… and then they were upon her.”

“So clean and understated,” Reddy says. The genre of the story has shifted: What began in “rural realism” has transformed into horror. He points to Jackson’s choice of “upon,” a formal-sounding word. That word—that moment—is “where horror suddenly happens.”

Torsten Reimer, University librarian and dean of the University Library, is a historian by training, specializing in early modern English history. So he is well aware that “censorship has been around for a very long time,” he says.

Nonetheless, when he left the British Library to work at UChicago, he never imagined he would be living “in a democracy where books are being removed from libraries,” he says. “The situation of book bans has gotten a lot worse since I’ve come here.” That was just three years ago.

Reimer is speaking at a Winter Quarter event at the Regenstein Library—Fireside Chat with the Dean: Banned Books—designed specifically for students. The Brutalist Reg, built in 1970, has no fireplaces to chat by the side of, so a large screen on the wall behind Reimer plays a video of a cheerfully crackling, heatless fire.

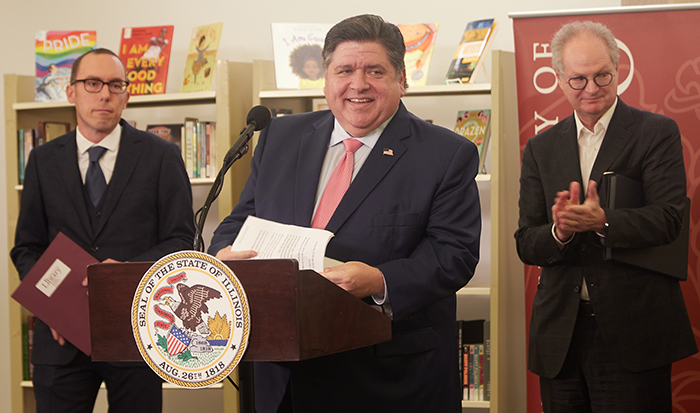

In October 2023, in the same room, Reimer—along with Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker, Lieutenant Governor Juliana Stratton, and UChicago President Paul Alivisatos, AB’81—held a press conference about the University’s banned books initiative. The library is building a collection of books that have been banned in one or more US libraries.

The point is to make the books available to the public as well as to researchers. If you live close enough to Hyde Park, you can get a visitor’s pass and read the books in person.

If you don’t, you can ask your local library to request them through interlibrary loan, and you can also read more than 1,300 banned books online. The library is collaborating with the Digital Public Library of America to make e-books available to readers in Illinois and across the nation.

“I should maybe first explain what we mean when we say book bans,” Reimer says to the students, who are snacking on pizza and soda.

A “challenge” occurs when a person or group asks a library to remove a book from its collection. If the challenge succeeds and the book is removed, “that’s what’s generally referred to as a book ban,” he says.

Because book bans tend to be local and spotty, they’re difficult to monitor. Organizations that track bans, such as PEN America, consider a book to be banned if “at least one version of this book has been banned in at least one library somewhere in the United States,” Reimer says.

For adults who can buy their own books, maybe this doesn’t matter so much. But for kids, especially young kids, removing books from school and classroom libraries can put those books out of reach.

When Reimer was preparing for the October 2023 press conference, he read through PEN America’s list of over 1,500 banned titles. (Other organizations trying to track bans, attempted bans, and challenges have arrived at different figures.) “There was one title that stood out to me,” he says. He was so intrigued, he bought a copy for himself.

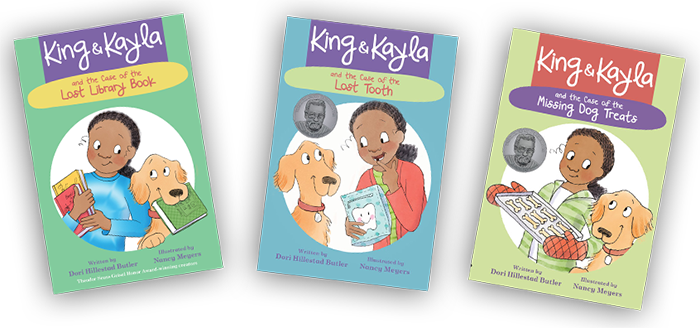

King & Kayla and the Case of the Lost Library Book (Peachtree, 2022), by Dori Hillestad Butler, is a chapter book, written for kids who are just starting to read on their own. The book’s simple story, in Reimer’s summary: “Together with her dog, King, [Kayla] goes on an adventure to find that book and eventually finds it and returns it, so she can borrow more new books from the library.

“I could not fathom why someone would want to ban this book,” Reimer says. “I’m still not quite clear, but this is the cover.” He holds up his copy. “And, yeah, the little girl on there is Black.”

I’m intrigued too. King & Kayla is a series with 11 books so far; eight of them made it onto PEN’s list. Two—The Case of the Lost Tooth (Peachtree, 2018) and The Case of the Missing Dog Treats (Peachtree, 2017)—are Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Books. The award, named for Dr. Seuss, recognizes distinguished books for beginning readers.

“So have you seen the book?” Butler asks, speaking over Zoom from her book-lined home office. She agrees with Reimer that race was the issue. “A lot of times they”—the people who challenge books—“don’t even read the book. Nowadays there are lists of books” compiled by pressure groups. (One of the largest is called, unironically, Moms for Liberty.)

“A person of color on the cover,” Butler says, can be enough to land your book on such a list.

After pushback from students and teachers in the Pennsylvania school district where they were banned, the King & Kayla books were put back on shelves. But PEN still counts this as a ban, it said in a statement, because “bans that are at first ‘temporary’ often become permanent.”

And in that school district, the fight to ban other books goes on.

Samira Ahmed, AB’93, MAT’93, first heard stories about her books being “soft banned” around 2021.

“Soft banned,” she says (speaking over Zoom from her home office, which, like Butler’s, is filled with books), “essentially means a book is being pulled from a curriculum or library shelves. But it’s not going through any kind of laid-out process by a school district or library board.”

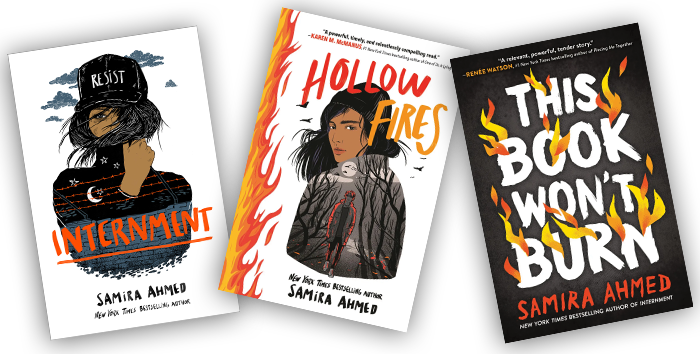

Ahmed, a New York Times best-selling author, has written six novels for young adults (YA), as well as two books for middle graders and the five-volume comic book series Ms. Marvel: Beyond the Limit (Marvel Worldwide, 2021–22)

Her second YA novel, a dystopian story called Internment, was published in 2019 (Little, Brown and Company). Inspired by President Donald J. Trump’s first presidential term, Ahmed imagined a United States where Muslims were sent to concentration camps, like Japanese Americans were during World War II.

Fast forward a few years. At a conference Ahmed meets a teacher who had planned to include Internment in her lit circles. “A lit circle in high school,” Ahmed explains, “is a list of books kids can choose from, and they form something like book clubs.” (Before Ahmed became an author, she was a high school teacher.)

The teacher was told by other teachers in her department that Internment didn’t belong in their school, which has no Muslim students. (Ahmed has a “pat response” to this argument: “You have Lord of the Rings in your school library, and you don’t teach hobbits.”)

The teacher was worried. She was a single parent; the other teachers outranked her. Would they take the issue to the principal, the superintendent, the board? She pulled the book. But she wondered if she had done the right thing.

“She asked me this question that has just been burned in my brain,” Ahmed says: “‘Samira, my question to you is, how can I be brave?’” It’s like a line from a dystopian YA—The Hunger Games, Internment—and I’m so taken aback, I tear up.

Ahmed shares another soft-banning story that’s funnier, if your sense of humor is bleak enough. A teacher in a different district put in a purchase order for books, including Internment. The shipment arrived, but Internment wasn’t in it.

The teacher asked the staffer who placed the order what happened. “This staff member,” says Ahmed, “who is not a teacher and is not an administrator and is not a librarian, says to her, ‘I don’t think we should have that book at our school.’”

So the teacher decided to “wage a very gentle, soft campaign.” She kept checking back, and checking back. Finally she asked straight out: “‘Why can’t you just put this purchase order in?’”

The response: “‘I don’t know. I guess I’m just prejudiced.’”

(The teacher eventually got the books, Ahmed says, but “it’s still not a feel-good story.”)

Ahmed’s books have been formally challenged too. In 2023 she spoke at a school board meeting in Niles, Michigan, in defense of Internment and her 2022 book loosely based on the Leopold and Loeb murders, Hollow Fires (Little, Brown and Company). Ahmed was struck by the fact that while she was speaking to the board, “not a single one of them made eye contact with me.” The district adopted a policy requiring parental permission to read certain books.

Along with soft bans and formal bans, Ahmed’s work also inspires personal attacks. “I guess any woman of color in publishing gets death threats or rape threats,” she says matter-of-factly.

“Here’s one I just got,” she says, scrolling. “This was on social media. ‘Leave America, you pedo.’” (For children’s authors who write about sex—or even those who don’t—accusations of pedophilia are depressingly common.) “This was last Friday. ‘You should go back to your country.’ ‘This is America, and we don’t want you here.’ This was last Thursday.”

Ahmed is not easily silenced. She serves on the leadership committee of Authors Against Book Bans; according to its FAQ, “we stand against ALL book bans, no matter where they are coming from on the political spectrum.” Ahmed’s most recent YA novel, about a girl who fights book bans in her high school, has an uncompromising—you could call it incendiary—title: This Book Won’t Burn (Little, Brown and Company, 2024).

But Ahmed’s work also comes from a softer place. She speaks tenderly of her own childhood library: “An old Victorian building, and they had a fireplace,” she says. “Obviously they didn’t have a fire in the library.” Ahmed remembers curling up in a big leather chair, reading a book, “so cozy and magical … like The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe kind of thing. I’m just here in this magical little world.”

Reading as a Writer: Obscenities was inspired by an email “that maybe I would have deleted on a bad day,” Chicu Reddy says.

The email invited faculty to create new courses on the topic of free speech. “I’ve been here for over 20 years now,” Reddy says, “and we all get into our grooves pedagogically, teaching the same classes for years.”

The College provided funding for a graduate student, Dana Glaser, PhD’24, to help design the course. Reddy and Glaser spent a year “thinking about free speech as a social and historical and political and cultural problem,” he says, “but also how artists might think about that question.”

Reddy has published three books of poetry, most recently Underworld Lit (Wave Books, 2020), “a multiverse quest through various cultures’ realms of the dead.” He has never been on the receiving end of a book ban. “I can’t say I’ve ever been a terribly transgressive writer,” he says, “or maybe person.”

He wonders if he’s a surprise to the students who enroll in Obscenities, thinking “they’re going to be signing up to study with some firebrand,” he says, someone wielding “a fire hose of obscenities in the classroom.” In fact, Reddy is soft-spoken and humorous, as well as extremely respectful of student work.

Why “The Lottery”? I ask. I’m still confused about why it’s on the syllabus. What makes that story obscene, exactly?

Because Jackson’s story occupies “that strange place between fiction and reality,” Reddy explains. Works of literature that “trouble that line” are often extremely upsetting to readers. “It tells a story about small-town America,” he says, “in a scene that looks a lot like voting.”

People who want to ban “The Lottery” have pointed to its violent ending. But Reddy doesn’t think that’s the real reason. “It challenges our sense of what participatory American life and community are all about,” he says. “That’s the obscenity.