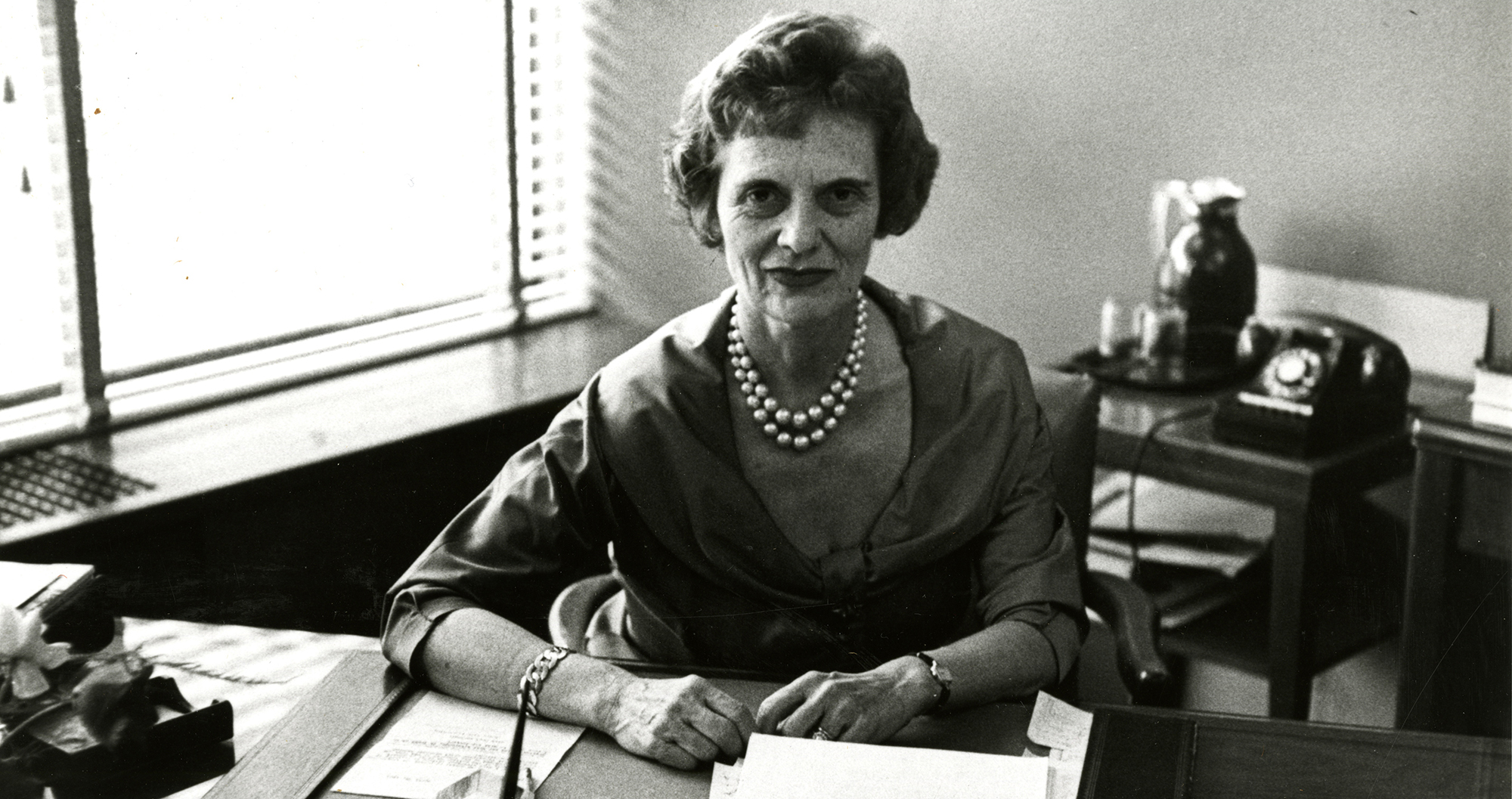

Mina Rees, PhD’31 (1902–97), helped scientific research flourish.

When mathematician Mina Rees, PhD’31, was elected as the first woman president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1970, her colleague F. Joachim Weyl wrote, “Any respectable description of what Mina Rees has done … will inevitably read like a concise history of American mathematics during the last few decades.”

A people person with a knack for translating between researchers and nonexperts, Rees played a crucial role in establishing government funding for the sciences during and after World War II. “I got the support only by being on hand all the time and being watchful,” said Rees. “It doesn’t come automatically.”

Rees was born in 1902 in Cleveland, the youngest of five children. Her family moved to the Bronx when she was 2. Though her career would take her around the country, she always returned to New York City and to the public schools where she was educated.

She graduated as valedictorian from the all-girls Hunter High School and went on to study mathematics at Hunter College, then a women’s college. “I found that the mathematics department was where I wanted to be,” she said. “It wasn’t because of its practical uses at all; it was because it was such fun!”

Rees supported herself by teaching while pursuing a master’s degree in mathematics at Columbia University. Eventually she enrolled at the University of Chicago, completing her PhD under the supervision of Leonard E. Dickson, PhD 1896, who had authored her college algebra textbook. She spent the next 12 years at Hunter College, rising to associate professor.

In 1940 the National Defense Research Committee was formed to bring together scientists to solve national defense problems. Rees was recruited in 1943 to the committee’s newly established Applied Mathematics Panel to serve as a technical aide and executive assistant to the panel’s director, Warren Weaver.

She believed she was chosen because of the extensive relationships she had built in the mathematical community during the previous decade. (Rees had always been very social, choosing to move out of her parents’ house shortly after graduating from college because she wanted to entertain frequently, and her mother was opposed to alcohol consumption.)

Her new job tested her people skills perhaps as much as her technical knowledge. Rees was responsible for making this unprecedented collaboration between researchers and government and military officials run as smoothly as possible. The Applied Mathematics Panel operated by contracting out problems submitted by military and government officials to scientific researchers. Rees translated each problem into mathematical terms and presented it to the panel so they could assess its feasibility. Once a problem was accepted, she kept the research on track, reported on progress to government and military personnel, and frequently wrote up final results.

Though it might have seemed unnecessary to nonexperts, the Applied Mathematics Panel researchers often had to develop new theory before they could solve a problem, and it was up to Rees to make the case for this pure mathematical research to government and military officials. To optimize the accuracy of explosives, for instance, researchers needed to understand how shock waves behave in the air and underwater—fundamental fluid dynamics problems. Because of Rees’s advocacy for pure research, the panel made foundational advances in disciplines including statistical analysis, mathematical modeling, numerical analysis, and computing.

At a time when the expression “girl-months” was used as a unit of time (how long it took a woman to perform a certain calculation on a desk calculator), Rees was the only woman on the Applied Mathematics Panel, navigating the male-dominated worlds of academia, the government, and the military. Four months after taking the job, she wrote to her friend Richard Courant, a member of the panel, to ask a favor. She was tired of people assuming she was Weaver’s secretary: “Will you please, in the future, when you introduce anyone of importance to me, say in a loud and clear voice, ‘This is Dr. Rees.’? Your muttered ‘This is our boss’ has consistently brought forth the assumption I speak of, and I can’t take it.”

By the time the Applied Mathematics Panel was disbanded in 1946, it had begun more than 200 research studies. “In the war you just worked day and night; you did everything,” Rees said. The view of New York Harbor from her desk on the 64th floor of the Empire State Building kept her sane through the long hours. Rees was recognized with the President’s Certificate of Merit and the British government’s King’s Medal for Service in the Cause of Freedom.

After the war, continued government funding of science research was seen as a national security priority, and Rees was asked to help develop the first postwar research program as head of the Mathematics Branch of the Office of Naval Research.

Rees wasn’t sure mathematicians would welcome government backing for their peacetime research, and she traveled the country to gather feedback. Her extensive outreach was partly the result of a postwar housing shortage in the capital: She could only find a hotel allowing a maximum stay of two weeks. “I made virtue of necessity,” she said, “and, every two weeks, vacated my room and went on a trip to a leading mathematics department.”

Based on what she learned, she put in place policies and practices—later adopted by agencies like the National Science Foundation, which Rees advised in its early days—that have characterized federal funding of the sciences into the 21st century, practices now facing serious challenges. She implemented graduate and postdoctoral research positions; summer, sabbatical, and travel funding; and financial resources for journals to share research broadly.

Rees is best known for helping to make the development of computers possible, but she first had to convince government and industry leaders that these machines weren’t just a fad. “Some influential people were of the opinion that there would never be enough work for more than a few of the large computers,” she said.

Rees disagreed. At the Applied Mathematics Panel she had overseen all contracts related to computing, so she had a clear view of where the field was headed. She understood the commercial and educational value of smaller, faster, and cheaper computers, and she funded studies in areas like numerical analysis that worked toward this end.

In 1953 Rees returned to Hunter College as dean of the faculty, and eight years later, when the City University of New York (CUNY) was established, became its founding dean of graduate studies, tasked with building a graduate school from the ground up. In 1985 the CUNY Graduate Center library was renamed the Mina Rees Library, the first library in the United States dedicated to a mathematician.

She retired as president emerita of CUNY Graduate Center (then the Graduate School and University Center) in 1972, the year after she served as the first woman president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Even Vogue took notice of that role, including Rees in a feature called “Liberated, All Liberated” alongside other women luminaries from the time. (Liberation had its limits, though: The editors felt it was important to point out Rees’s “terrific ankles.”)

Vogue aside, Rees never did make the same kind of headlines as the advances she made possible. But from her seat behind the scenes, Rees promoted decades of mathematical progress and helped reshape what careers in the sciences look like in the United States. Reflecting on her legacy in 1970, a colleague emphasized this human side of her work: “Her impact on the history of mathematics … lies in the changes she has wrought in the professional lives of many significant mathematicians of her time.”