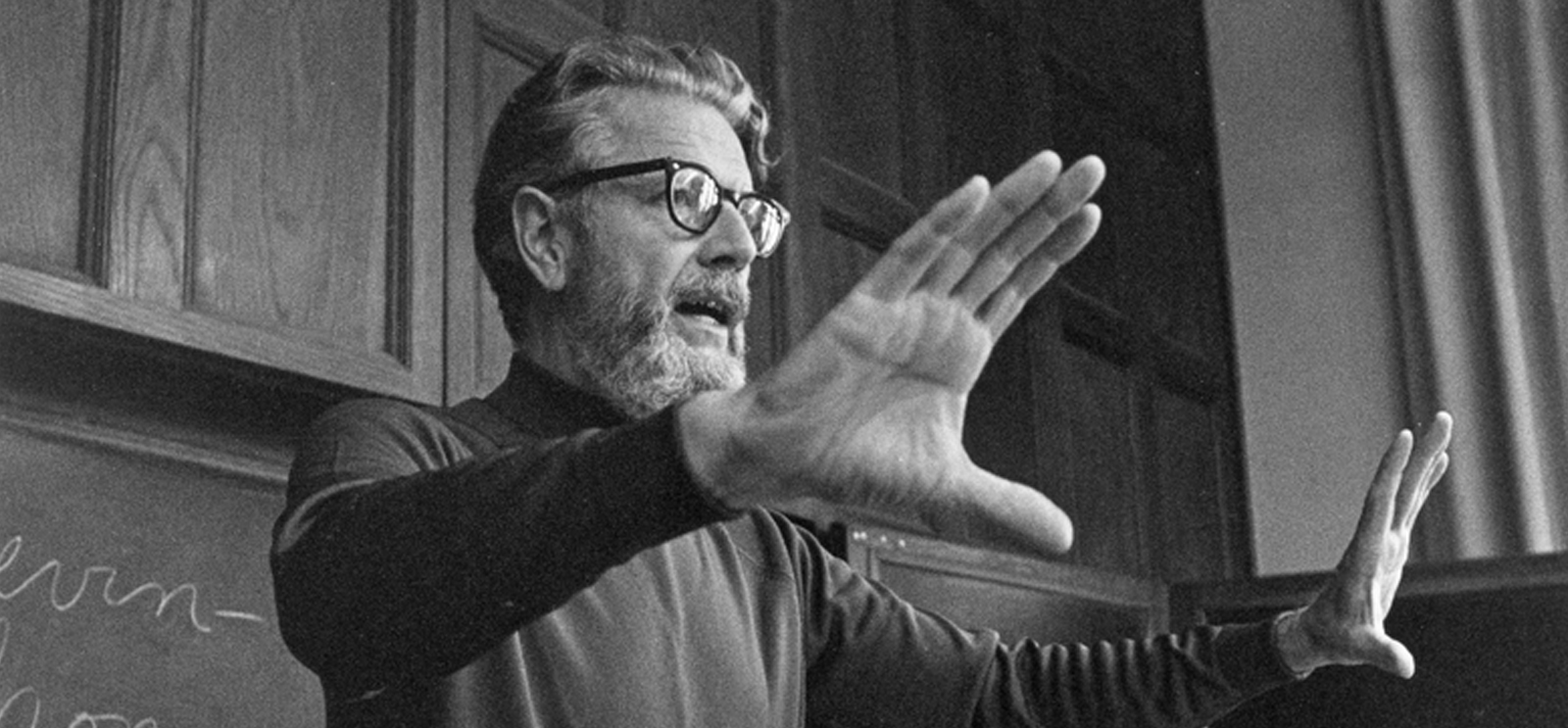

Wayne Booth, undated. (University of Chicago Photographic Archive, apf1-00818, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

A walk through campus sparks memories of Wayne Booth, AM’47, PhD’50.

There is a pleasure from learning the simple truth, and

there is a pleasure from learning that the truth is not simple.

—Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (1961)

As we prepared for our visit to campus, my 17-year-old daughter and I got into a disagreement.

“I want to be dropped off,” she informed me. As if this were an innocuous visit to a school friend’s, or to any college campus. “I don’t even want you to stay on the South Side.”

“Oh, but I’d like to see the campus with you.”

“You know what it looks like,” she said, in that cool tone that means: No arguments. “I don’t want you going with me to any more college visits.”

I was crushed. For the last year or so, I had been talking to my comrades in the parenting trade and poring over articles and books (Excellent Sheep, College (Un)Bound, and, of course, Colleges that Change Lives), as well as copious lists claiming to catalog “the best.” How to explain to her that strain of parental adoration: when you want to target them with the firehose of your powerful opinions about everything?

She reminded me of a visit to a sleepy Wisconsin college town. The rules had been negotiated. Even though I was under instructions to offer no commentary, to ask no questions, afterward I was accused of “opinionated facial expressions.”

I had sealed my own fate.

One outcome of our disagreement was a decision that her brother, 15, would accompany her. She wanted a sounding board who was not me, and he would be applying to college in two years anyway. After much discussion, it was allowed, because of transportation logistics, that I could stay on campus if I stayed out of view. At the steps of Rosenwald Hall, where two dozen young people gathered, many with their parents, I said goodbye.

Gazing up at the spread of ivy reaching the gargoyles, the gothic towers and up-to-the-sky archways, I wandered, nursing a grudge, searching for the madeleine that might release a torrent of consoling nostalgia. On any return, I explore the little neighborhoods that make up the campus. I surrender to a wash of recollections, all of them unbidden, many of them surprising, not all of them pleasant, but enjoyed nevertheless because of the temporal distance. They are no longer one’s own experiences, but those of a character in a bildungsroman in one’s own head. Every turn down a path, every room, is like turning the page of a new chapter. Oh, and then that happened.

I had fantasized that my children’s experiences in Hyde Park would be an unexpected next chapter in a book that I had not wanted to stop reading.

I camped out on the C Bench. As a college student I used to lounge there after class with a friend, gossiping, appraising students exiting Cobb Hall, exchanging whispered comments, but pretending to have deeper conversation. Now, as a middle-aged adult, I found myself musing on whether today’s students were better looking than we were 30 years ago, and I lost myself in this question, a bit of a koan, until I was startled by the sound of a tour guide’s voice. My children might, I realized, have glimpsed me eyeing undergraduates.

I am the embarrassing monster they dreaded I would become.

While the tour guide pointed to Classics, Wieboldt, and Goodspeed, I ducked my head but made the mistake of peeking above C Bench. My daughter was oblivious, her attention razor focused on the undergraduate docent pontificating on the lawn. But my son, designated bodyguard against parental narcissism, spied me spying him, and his eyes narrowed:

Damn your meddling ways.

They moved on.

Continuing my solitary search, I found myself wandering through Harper Library. The high ceilings had always had an irresistible soporific effect. Then I was in the café where I had worked. To this day I don’t know why I longed for any other vocation. Next I found myself drifting up the steps of the west tower of Harper Library, an ascent imprinted in memory with trepidation, then and now. I had not returned to this place in the 10 years since Professor Wayne Booth died.

Professor Booth had occupied a singular place of honor in my mind. Other than my father, he was the only other Wayne I had ever met. Unlike any of the well-known Waynes, he was not a serial killer or a baby-faced crooner. He had white hair; a white beard; a long, handsome face; heavy, dark-framed glasses; a ubiquitous turtleneck. In his writing, as in his speech, he relied on an elegant form of punctuation—the em dash—which to this day I cannot use without hearing the gentle cadence of his conversation, the ways he layered observations when he talked about poems and stories.

One afternoon, early in my freshman year, I had arrived in his book-lined office for our weekly writing tutorial group. Surprised, he apologized for mistaking the time and not being prepared. We arranged chairs for the other four first-year students and then marveled when they never showed. I felt betrayed. How could they stand up Professor Booth? Damn their apathetic souls.

“I guess we’ll spend the hour on your paper,” he said. Outwardly I stared back blankly; inwardly my stomach rolled.

We were reading Yeats’s “Sailing to Byzantium.” I thought I had nailed the interpretation.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

Our time together was the longest hour of my life. To this day, every strand of wisdom he offered me comes back whenever I write anything. “In terms of the mechanics of composition, you’re a solid writer,” he offered, leaning in with intense focus. “But you play it too safe. You’re not delving into the really messy complexity of this poem. You need to take risks. That’s what makes a piece of writing rich.”

An hour later, the other four students arrived, at the actual scheduled time.

I blanched, as if I had been caught shoplifting something precious. Had I really insisted that I had the time right? Really?

Professor Booth welcomed the four students. We spent another hour discussing their papers. It was as if I had made no mistake, that I had deserved the gift of that time.

Midway up those stairs of the west tower, I paused, a 50-year-old man, timid as the first-year student I had been, realizing that at my age I was only a few years younger than Wayne Booth had been in that recalled moment. More than lectures or books or classroom discussion, as an undergraduate I learned through experiences of dissonance. Potent as the deep, hot, red-faced embarrassment I felt in that moment, there was an insistent grace. His deference to my wrongness, his implicit forgiveness, made him larger, more powerful.

I turned around. I descended the stairs. I didn’t want to see anyone else in that office.

Returning to Rosenwald Hall, I watched my daughter and her bodyguard linger as the docent talked up the school. I stayed about 20 feet away—it was, after all, the time we had agreed I would return to them—and gave them a respectful distance. From the ground, I could see the windows high in the west tower and I imagined the distant view of me, nervous father of teenagers, from that particular window, where for so many years the other Wayne might have contemplated the landscape of students wandering to and from their teachers. Without comment or question, I rejoined my children. We strolled over to the Medici for vanilla and chocolate milkshakes. They were proclaimed—through no editorial prompting of mine—the best milkshakes ever.

Wayne Scott, AB’86, AM’89, is a writer and teacher living in Portland, Oregon. Visit his website at waynescottlcsw.com.