Harriet Monroe portrait (above) and cover art from the Poetry magazine archives; photos of letters by Lydialyle Gibson, with permission from the Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

As Poetry turns 100, a look back at the back-and-forth between Harriet Monroe and her readers.

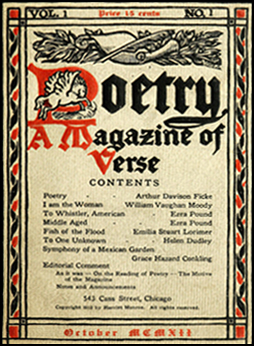

It’s been 100 years since Harriet Monroe founded her “small monthly magazine of verse” on the tenth floor of the Fine Arts Building. After local business leaders pledged $5,000 to get the project off the ground, the first issue of Poetry (which included a posthumous poem by former UChicago English professor William Vaughn Moody—and a typo misspelling his name on the cover) mailed to subscribers in late September 1912.

Letters to the editor began rolling in not long after. Some came from admirers, but others—familiar to any magazine editor—came from dissatisfied readers and would-be contributors. Last month I spent an afternoon at the University’s Special Collections center, where a seemingly inexhaustible archive of Poetry records and Monroe papers preserve some of those early exchanges between the editor and her public. “I shall send you no more,” insists one disappointed writer after his submissions were declined and returned, “not because my poems are not meritorious, for they compare more than favorably with anything you have published.” He went on to call the magazine’s poetry “inane,” “spiritless,” and “woefully puerile” before challenging any writer from Poetry’s pages, including Monroe herself, to a poetry-writing contest to be “ajudged [sic] by three fairly selected jurors.”

Letters to the editor began rolling in not long after. Some came from admirers, but others—familiar to any magazine editor—came from dissatisfied readers and would-be contributors. Last month I spent an afternoon at the University’s Special Collections center, where a seemingly inexhaustible archive of Poetry records and Monroe papers preserve some of those early exchanges between the editor and her public. “I shall send you no more,” insists one disappointed writer after his submissions were declined and returned, “not because my poems are not meritorious, for they compare more than favorably with anything you have published.” He went on to call the magazine’s poetry “inane,” “spiritless,” and “woefully puerile” before challenging any writer from Poetry’s pages, including Monroe herself, to a poetry-writing contest to be “ajudged [sic] by three fairly selected jurors.”

Two weeks before Christmas in 1913, another letter writer sent a short note—“a magazine which I myself dislike, I wish to send it as a Xmas gift to none”—and appended a four-line poem:

Oh! how I hate your effeminate songs;

The repeating echoes of the dead throngs;

Your written lines in dying numbers flow;

And, to sing of pain or joy you don’t know!

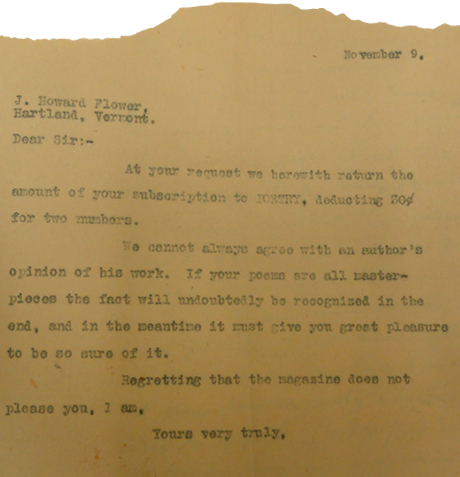

Monroe remained unperturbed. How often must she have sent a response like the one below to an unhappy correspondent?

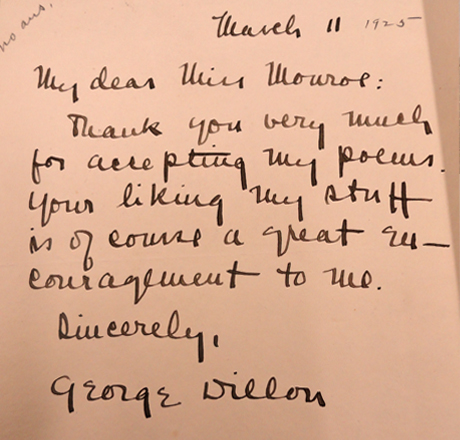

And yet. Among the boxes of papers and poems and letters, I also found this note, from George Dillon, PhB’27, who at the time was still an undergraduate in the College:

Five years after his graduation, in 1932, Dillon won a Pulitzer Prize for his poetry. Five years after that, he became the editor of Poetry magazine.