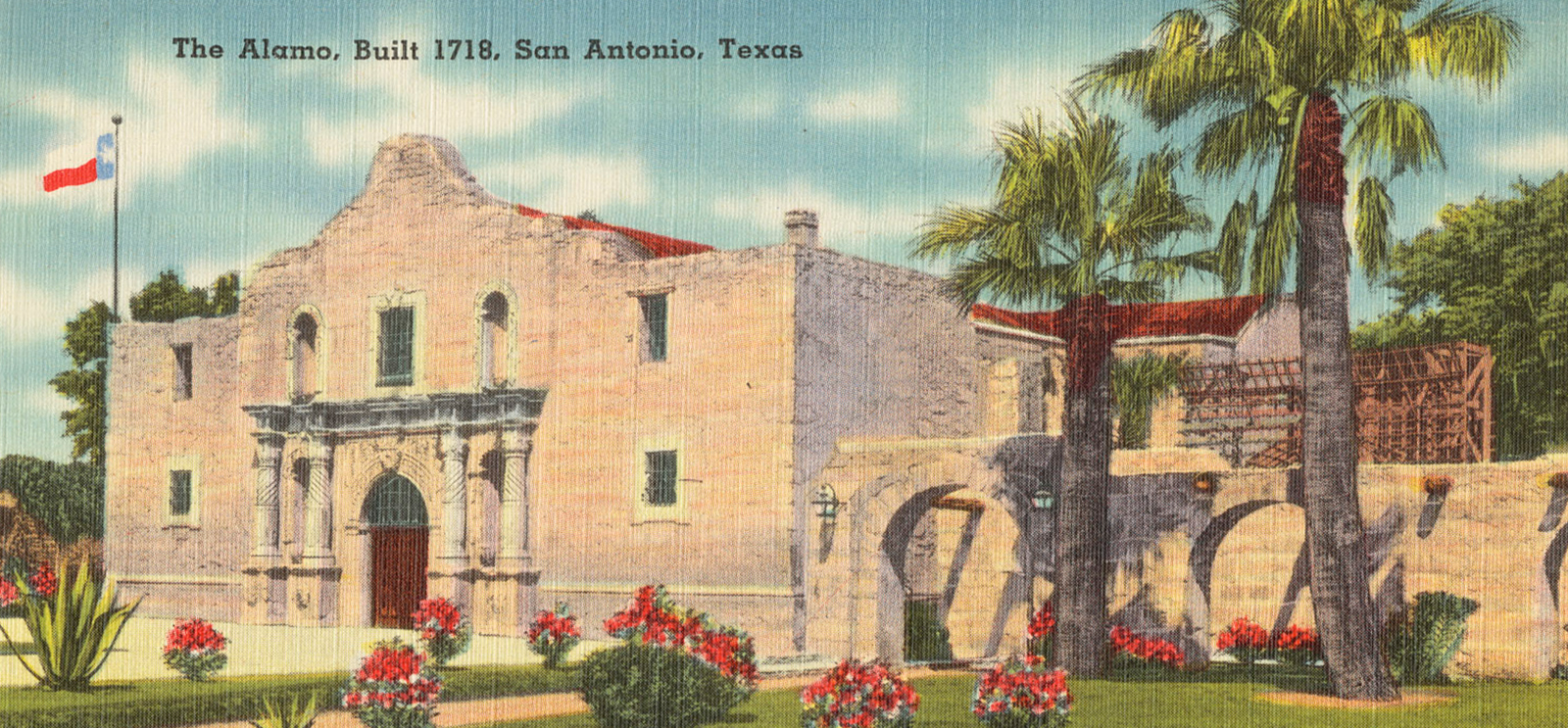

The Alamo is one of San Antonio’s five Spanish missions. (Boston Public Library, the Tichnor Brothers Collection, cc by 2.0)

Susan Snow, AB’84, worked to gain World Heritage designation for five Texas landmarks.

Many of us have forgotten everything we learned about the Alamo—except that we’re supposed to remember it.

So, a quick refresher: the Alamo, or Mission San Antonio de Valero, was one of five missions established in San Antonio in the 18th century. Like Spain’s other missions in what are now California, Texas, and Mexico, it was intended to convert the region’s indigenous peoples to Christianity and to provide a territorial foothold for Spain.

In 1836 about 200 Texan rebels died trying to defend the Alamo, by then a military outpost, from Mexican forces. Their defeat inspired general Sam Houston’s famous rallying cry as he led the Republic of Texas to independence from Mexico later that year.

Susan Snow, AB’84, needs no reminding. An archaeologist for the National Park Service in San Antonio, Snow coordinated—or “cat herded,” as she likes to say—the effort to gain World Heritage designation for the five San Antonio missions from the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The five sites were nominated together, though the Alamo is operated by the Texas General Land Office, while the other four missions are run by the National Park Service.

When the UNESCO nod came in 2015, it was a proud moment for San Antonio. It meant the missions had “the same global influence as the Taj Mahal or the pyramids of Giza,” Snow says. They are now among 23 World Heritage sites in the United States (others include the Grand Canyon and the Statue of Liberty) and more than a thousand worldwide.

Before moving to San Antonio, Snow studied Latin American and European colonial archaeology, first at UChicago and then at the University of Calgary. That prepared her for the work awaiting her in San Antonio, which includes education, preservation, and collections management for the four missions that are part of the National Park Service.

At many other mission sites in California and Texas, only the churches have survived. In San Antonio, every component of the mission system remains, from farm fields to workshops and granaries. Not only are the churches still standing, several are active parishes.

Long before those churches were built, south Texas was home to nomadic tribes of hunter-gatherers, collectively called the Coahuiltecans. Like other indigenous populations near Spanish missions, their numbers plunged in the early mission period because of disease, conflicts with the Spanish and other native groups, and the introduction of new sexual mores that reduced birth rates. Some Coahuiltecan languages and cultures were destroyed altogether, while others were reshaped through religious conversion and intermarriage propelled by the missions.

The gradual melding of Spanish and Coahuiltecan cultures gave rise to the distinctive Tejano culture that characterizes South Texas today. “You can’t be from San Antonio or live in San Antonio without being influenced today on a daily basis by the missions that were established here in the 1700s,” Snow says.

Snow, along with many civic partners in San Antonio, spent nine years convincing UNESCO of the missions’ enduring importance. Each stage of the process required meetings, proposals, and paperwork. The nomination first had to earn the support of the US secretary of the interior, then undergo review by multiple federal agencies before advancing to UNESCO for consideration.

To gain World Heritage status, sites must prove they are of “outstanding universal value” by meeting one or more of 10 selection criteria. The missions made their case under criterion two: “to exhibit an important interchange of human values.”

Not all Texans were thrilled by the prospect of UNESCO’s imprimatur. Shortly before the decision on World Heritage status came down, one state senator proposed a bill to prohibit foreign control of the Alamo. It stalled after fellow lawmakers pointed out that World Heritage designation does not affect a site’s ownership.

Yet by and large, San Antonians have “really embraced the status,” Snow says. She hopes community events like the annual World Heritage celebration in September will help locals remember “they have this important resource here and that it should be part of their bragging rights too.” After all, “it’s the history of the world that we’re preserving.”