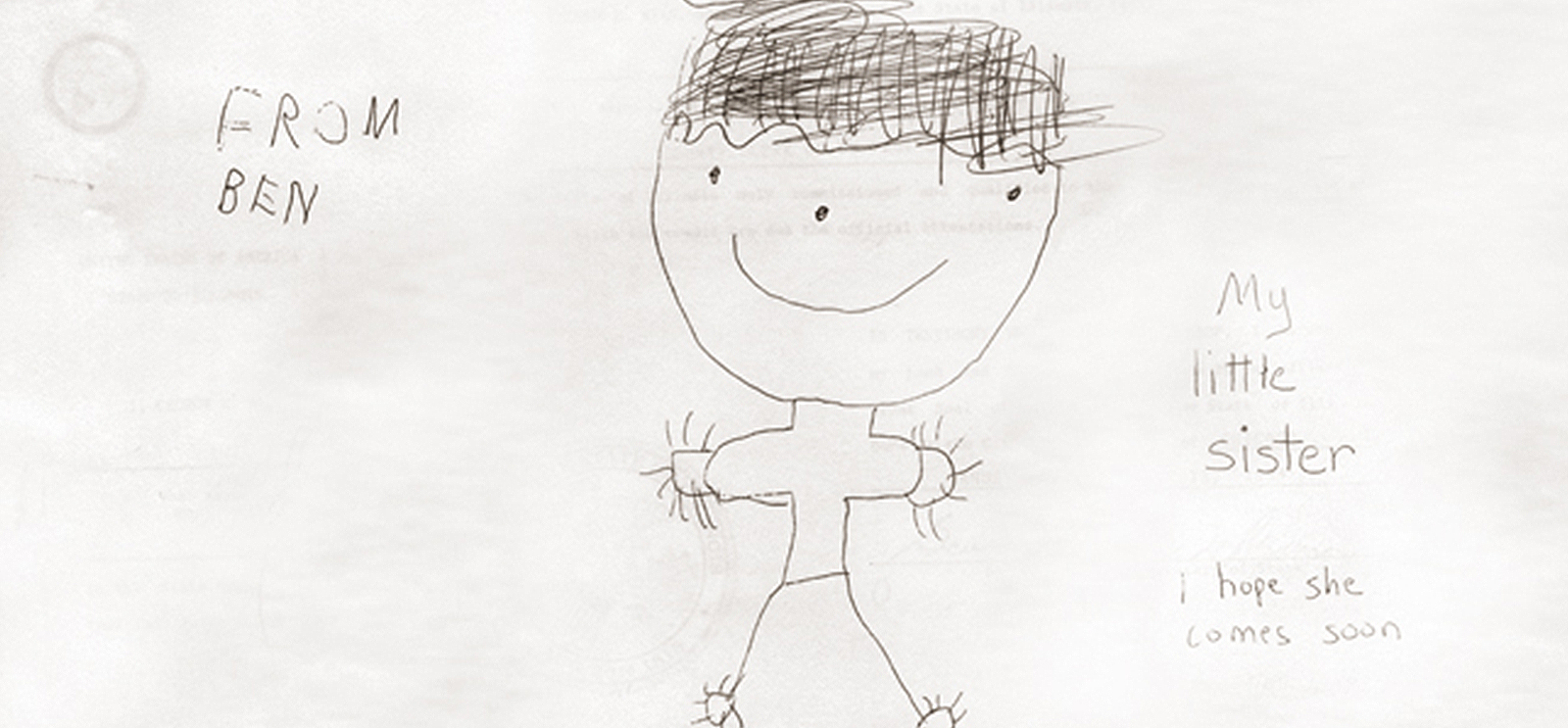

Olin's son eagerly awaited his sister's arrival. (Illustration courtesy Margaret Olin)

Before her daughter arrived, a baby photo from the orphanage was the only thing the author had.

She's about to scream; that's the only explanation." Mom's trying to analyze a photograph, or rather a photocopy of one. In it, a baby lies in a crib, arms outstretched. The sallow colors of the reproduction drain the cheerfulness out of her pink dress and blue flowered mattress. Mom is contradicting our pediatrician. He said, "She has cerebral palsy. Many of these children from Third World countries have serious disabilities."

A one-page medical report stapled to the photocopy explains that five-month-old Sheba has had all her immunizations and a test, negative, for AIDS. These two pieces of paper compose the first positive response to the many letters we sent earlier in the fall to adoption agencies. We can sign across the picture and return it to signal our acceptance, but our social worker tells us to show it first to the pediatrician who takes care of our six-year-old son, Ben. "Adopt an American child," the doctor says, sending us away with offers to connect us with right-to-life groups.

Instead of contacting any of them, my husband, Rob, and I go home and stare at our photograph for hours. Her legs and arms stick out like twigs on a snowman. Mom continues: "They put her down to take the picture, and now she's mad." At first only my mother and sister mull this over with us, but then the rest of the extended family joins in, and soon many others voice their theories. Most of us think Sheba should see a doctor in India, and the University's Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, near our home, proves a great resource. Within days I have more recommendations for pediatricians in Hyderabad, India, than in Chicago. Some months pass, and in the winter I finally convince the orphanage to take Sheba to one of them. A ten-page report arrives, certifying the healthy development of a small orphan in every possible respect. The only problem is that the name of the healthy orphan is Rebecca. Soon Rebecca's prospective adoptive parents in Texas have more information than they need. There is, after all, nothing wrong with Rebecca's photograph.

What can a photograph tell us? I must expect a great deal, because in my frustration I rummage through piles of them: photographs of Ben at that age, of myself, of our friends' children. But nothing compares. Once a child can sit up, no more pictures show him lying down. Pictures of American children in families are progress reports; they demonstrate development: "Show us how you can crawl, sweetie!" I pore over photographs of Sheba and the other children in her orphanage. Against the blue mattresses, you can count every limb, every finger: the pictures are inventories.

Spring comes. One day I set off down Chicago's Lake Shore Drive, photocopy settled next to me in the passenger's seat, for an hour's drive to a suburban hospital. There Sheba's photograph and I have a consultation with a neonatologist, whom another friend has found for us. Doctor Caplan, I am told, has an adopted child of his own from South America. We will have a second opinion.

He examines the photograph and the list of inoculations. He patiently explains what our (by then former) pediatrician saw. He doubts it is cerebral palsy, although that's possible. Sometimes, he says, malnutrition in pregnancy can cause weakness in the legs and make them seem stiff. Often it goes away. Sometimes it doesn't. "But," he adds, smoothing the crumpled edges of the photocopy, "you don't really care, do you?" As he returns the photo, he adds: "She looks alert."

On the long drive home, I ask myself when Rob and I became the parents of a photograph. The moment came, I think, before the photograph did, during a telephone call from an adoption agency. A baby girl named Sheba was available in Hyderabad. "Shall we send you her picture?" The photocopy that arrived soon afterward has served ever since as a material token to stand in for the absence of a girl whose mother I have been ever since I first heard her name. It is a placeholder to introduce to the relatives, to take to appointments, to save a spot in our family until Sheba, its namesake, arrives.

It is lucky that I know this now, because although we sign our photocopy the next day, and soon receive the original snapshot in the mail, the rest of the process will take an entire box of staples and the help of many: senators, State Department officials, and other adoptive parents including Rebecca's, with whom late-night phone calls will have made us long-distance friends. More than two years will pass before Rob, Ben, and I sit in the office of an orphanage in Hyderabad, facing a door through which a long-awaited caregiver leads a three-and-a-half-year-old girl. "She doesn't look much like her picture," our son comments.

That was 15 years ago. It did indeed take years before Sheba walked very much. She preferred to skip and twirl, run and dance. She could be lethal with a soccer ball, as many of our family snapshots show. Soon she will leave for college, and we will treasure those photographs.

Margaret Olin is a senior research scholar at Yale Divinity School and the author of Touching Photographs (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).