Martin Luther posting the 95 Theses on the door of the Wittenberg Castle church in 1517. (Original painting by Ferdinand Pauwels, public domain Wikimedia Commons)

Remembering Martin Luther’s far-reaching legacy half a millennium after the 95 Theses.

Friar Martin Luther was naturally at home in monasteries, churches, and courts.

Surprisingly, this religious figure was, and is, almost equally at home in universities. His movement was born 500 years ago in an upstart German university at Wittenberg and is being commemorated and reappraised in higher academic institutions worldwide. Scores of colleges and universities are named after him, not only in northern Europe, where the movement that came to be called the Reformation was born, but also in global outposts, such as the young Martin Luther Christian University in Meghalaya, India. Up to 100 million Lutherans can be found around the globe, first in Germany and Sweden, then in Ethiopia and Tanzania, which come in third and fourth in Lutheran population surveys.

Universities are home to libraries, where writings of Luther abound in 120 large German-volume editions, while his bounty of books and pamphlets testify to the part the printing press, a recent invention, played in the Reform movements. Catalogers locate his writings, their analogues, and the writings of his colleagues on shelves in sections marked history, arts, sciences, and all the humanities, including, of course, theology. Psychologists probe records of Luther’s often-tortured and revealing inner life. Economists talk about “the Protestant ethic,” in many forms influenced by Luther.

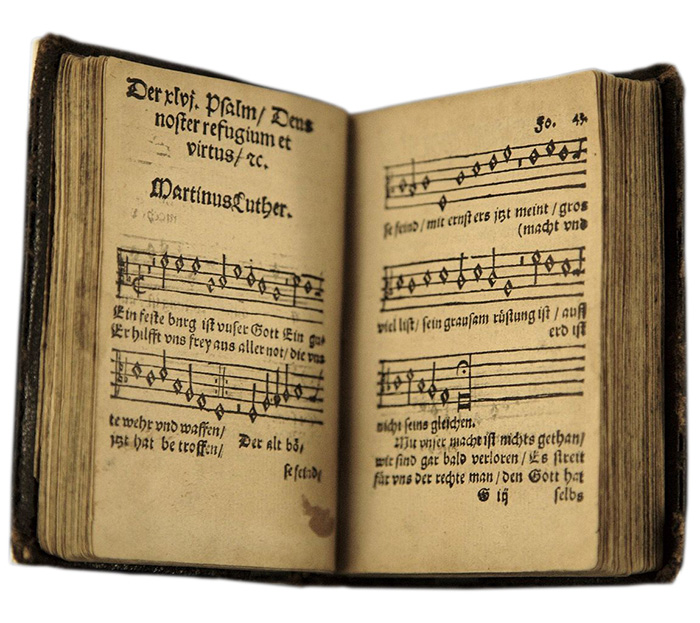

Among the visual arts, Luther favored many, including paintings by German artists and woodcuts by Lucas Cranach, a witness at the ex-friar’s wedding. It was through music produced or inspired by Luther that the Reformation took hold in parishes and homes. Luther and his colleagues helped move church music and musicians from remote choir stalls to the crowded benches of ordinary church people. His hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” came to be identified as “the Battle Hymn of the Reformation,” with the metaphors and reality of wars all too relatable to Luther and other Reformers.

In quieter settings, he and his colleagues turned out hymns that were sung in schools and during congregational worship. A whole pop culture emerged from this, and the grand cantatas and masses composed by Johann Sebastian Bach and his near peers are its legacies in serious concert programs. Rare is a university chorus that does not prize and perform this heritage.

Luther, of course, was not solitary in his home life and work. Other monks and friars broke vows, affirmed marriage, and found mates. Luther helped “marry off” a group of young nuns as they fled their convents and himself married one who was left over in that domestic lottery. She was Katherine von Bora, a very gifted and loving manager of the Luther-Haus, which was always open to guests, especially students. Kate gave birth to six children, kept the books, tended to her husband in the turmoil of radical changes in church and university, hosted their live-in guests, served meals, brewed the beer, and came to be revered by women, who were becoming prominent in Protestantism.

The Lutheran version was by no means the first reform movement to unsettle late-medieval Catholicism. A century before Luther, the Bohemian Jan Hus and other leaders had been articulate enough, in challenging Roman Catholic authorities, popes, and emperors, that they risked all, and Hus was burned at the stake as a heretic. In England, leaders in the restless wing of the Catholic Church made the Bible available in new translations and questioned many traditions, even as they began to move away spiritually from Rome. Through central Europe, early nationalist movements blended the Christian language of the cross, rooted in the church, and the language of the sword, symbolizing dealings with the state.

Some scholars like to describe a collection of many territories of the Holy Roman Empire as a tinderbox, ready to explode into fire, and they see Luther and other university teachers and preachers as strikers of the matches to ignite them. Of reform, Luther once said that while he and his friends in Wittenberg drank beer, God moved in and brought freedom and grace to the masses.

The most direct subject of the turmoil for a troubled and creative theologian had to be God. For Luther and his spiritual kin, “God” meant the God of Christian faith. An old book on my shelves since student days, Philip S. Watson’s Let God be God! An Interpretation of the Theology of Martin Luther (Muhlenberg Press, 1947), elaborates. Luther and those associated with him were surrounded by a God-based culture, imposed on all by church and state, which were until then ordinarily linked. The Reformers claimed that the official church did not let God be God. In their eyes, the church leaders remade God to match their own interests, needs, and private revelations. In practice, God was cut down to cultural size and not left free to rule or to save humans.

To rule meant to govern personal and social life in terms provided in the divine commandments, as received in the Bible. They were usually propagated and administered through the church. Those who failed to keep God’s law, as interpreted by the church, would suffer in this world and then eternally in a vividly imagined fiery scene to come. On the other side of the curtain of death there was promised a way of thriving with a gracious God in total fulfillment and happiness. Those Christians who kept the divine law would be rewarded with “salvation,” the promised vision and experience of God. Along the way there developed a kind of halfway house called purgatory, where the sinners—everyone, that is—were to be painfully prepared for the benign realm, usually called Heaven, by being purged of the account of sins and doubts that afflicted all.

It is easy to see how that domain of total and fateful choice could be exploited, and it was. The condensed story says that the pope, wanting to build colossal St. Peter’s church in Rome, needed funds. These were more abundant and less spoken for in German and neighboring lands. So, picking up on a few undeveloped clues in the tradition, enterprisers in German lands peddled indulgences, as if they were tickets redeemable to reduce the time spent in being purged. Luther and his fellow preachers took on the indulgence peddlers head-on, and things were never the same again. And the public rejoiced.

That telling oversimplifies a complex story, but other versions reinforced its main theme that humans are condemned and need redemption, which meant being brought back to God. And here was a dramatic, fresh pitch of Luther and the Reformers. Instead of winning eternal life by buying it, making pilgrimages, or following other rites, people simply had to hear and believe the word of God, channeled through the Bible and the preached word. All words of divine grace, they taught, center in God’s loving action in Jesus Christ, faith in whom these Reformers shared, though often in conflicting interpretations. Luther and company insisted that they were not rejecting the message of the Church after 15 centuries, but were listening to it without the clutter of law and superstition. They were “letting God be God.”

That project gathered the energies of movements including the Reformed in Switzerland and the Netherlands, and the Anglicans and others in England and Scotland. Some of these were quite different from Luther’s version, many finding the Lutheran way too compromised, calculating, and cautious. There developed what is often thought of as “the left wing of the Reformation,” which preached radical separation from the Catholic way. In the patterns of that time, people were compelled to go along religiously with their rulers, whether Catholic or Protestant, conservative or radical. All professed in their creeds that they believed the Church to be “one,” but the Lutheran and multiple other reform movements led to the appearance of many churches.

In our ecumenical age, Luther is revered by Lutherans and many other Protestants (and Catholics). He and his themes are studied and often approved in ways little anticipated. His heirs today do not disguise or hide his faults. In his later years he turned notoriously anti-Judaic—or, in today’s terms, grossly anti-Semitic—when Jews, with whom Lutherans shared the ancient covenant with God, did not accept Jesus Christ and the salvation Christians believed he brought. In our time, the 100-plus Lutheran church bodies around the world unanimously have united in repenting, which means affirming a change of heart with respect to Jews. They acknowledge that, for all their efforts, they have a long way to go. But today very many observances unite Lutherans, Catholics, and others in prayer and common action.

In this 500th year, the calendar points to countless Lutheran and Protestant activities: conferences, publications, festivals, hymn sings, and more. Many who participate in them, whether on university campuses, in classrooms, summer camps, Bible studies, advanced seminars, or local congregations, will find vast changes in the world separate them from much in Luther’s world. But in the whole range of these bodies’ participations and observations, one goal is nurtured broadly and deeply: to realize and affirm fresh ways of “letting God be God.”

Martin E. Marty, PhD’56, is the Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at the University of Chicago, where he taught for 35 years. He is the namesake of the Divinity School’s Martin Marty Center, focused on religion in public life, and author of Martin Luther (2004), from the Penguin Lives series, and October 31, 1517: Martin Luther and the Day that Changed the World (Paraclete Press, 2016).