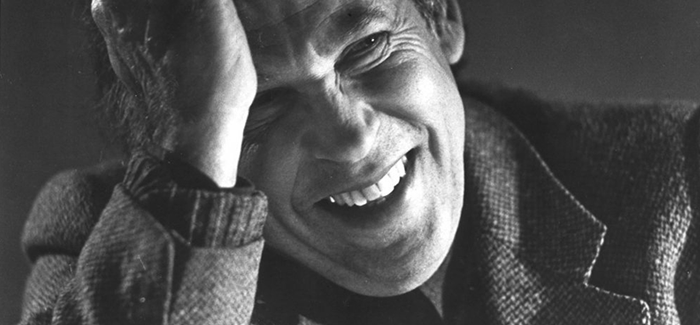

Bernard Sahlins, AB’43. (Photo courtesy Second City)

At a memorial service for Bernard Sahlins, friends and family recalled the Second City cofounder’s passion for his work, which in recent years included directing staged readings of verse plays for the Poetry Foundation.

Even after the seats were full and the lights started going down, people kept arriving. They lined the walls and crowded in at the back and climbed up into the balconies looking for more room, all of them coming to say goodbye to Second City cofounder and Chicago improv patriarch Bernard Sahlins, AB’43, who died this past June at 90. Among the audience were big names like actors William Petersen, Joan Allen, John Mahoney, Amy Morton, and Sahlins’s brother-in-law, British actor Geoffrey Palmer. During the September memorial service, held at the Chicago Shakespeare Theater, speakers told story after story about Sahlins’s smarts and spontaneity and madcap adventures, lapsing now and then into the present tense. By the time things wound to a close with the comical “Goodnight Song” performed by a cluster of Second City alums—including Bill Murray, who darted onto the stage just as the music swelled—the lofty Shakespeare Theater felt a little like the comedy club Sahlins founded in 1959: a couple hundred people crowded shoulder to shoulder in darkness, laughing long and loud, even as their emotions sometimes caught in their throats. The list of eulogists included many close friends from Sahlins’s professional life—not only at Second City but also Steppenwolf Theatre, the Chicago International Theatre Festival, the Shakespeare Theater, UChicago’s Court Theatre—bearing out Sahlins’s frequent admonition to young people: do what you love, he told them, and make no distinction between work and play. Speakers remembered him as a mentor and a big brother and a remarkably messy eater. (“Bernie was famous for his table manners,” recalled his brother Marshall Sahlins, an anthropologist and UChicago professor emeritus, “including the ability to eat a hot dog and get mustard on his back.”) He was a kid who never grew up, and a provocateur who never grew old. “What I have been feeling since Bernie died is an unimaginable silence,” said Nicholas Rudall, a Court Theatre cofounder and UChicago classics professor emeritus. Sahlins was Rudall’s friend for 40 years, since Court’s early days, and beginning in the 1990s the two collaborated on staged readings of verse plays, sponsored by the Poetry Foundation. “He knew how to take you under his wing, to teach you—and to be impossible,” Rudall said. “Because, as everyone said, there was this wonderful, generous, critical mind, but an enormous, wonderful obstinacy as well.” Second City CEO Andrew Alexander put it more plainly: “Well, Bernie Sahlins drove me nuts,” in part because Sahlins was almost always right. He knew the theater business, he knew Chicago, and he knew what was funny. “There are more than a few actors,” Alexander said, “whose lives are made better the first time they make Bernie laugh.” Sahlins’s nephew, British television director Charles Palmer, recalled jokes that had delighted him and his younger sister, and antics involving balled-up newspapers, bawdy songs, and baby chicks. “There was something childlike about him that we related to,” Palmer said. “Like us, he got bored and was told off for his table manners, and like a child he was always looking to have fun.” Chicago Tribune theater critic Chris Jones called Sahlins a great Chicagoan. “His work has always ennobled this city,” he said. “His has been comedy at its highest reaches, comedy of the mind, unafraid of classical references or a bit of Heidegger in the punch line, but it’s OK if there were beer stains on the table.” Second City alums Tim Kazurinsky and David Pasquesi thanked Sahlins for demanding that they never dumb down their performances for the audience. “Bernie didn’t suffer fools gladly; in fact, he didn’t suffer them at all,” Kazurinsky quipped. “But thank God he wasn’t above hiring them.” Offering bits of family history (“you probably didn’t know that Bernard George Sahlins was named for George Bernard Shaw”) and memories of his older brother, Marshall Sahlins expressed a loss both personal and universal. “Brothers are parts of one another,” he said. “Now I’m incomplete. But then everyone in the human brotherhood who knew and loved Bernie, and the millions beyond whom he made laugh and think, have lost something of themselves. When someone he admired died, Bernie was fond of quoting a line from Hamlet that all of us could now say of him: ‘He was a man. Take him for all in all. I shall not look upon his like again.’”