(Scott Olson/Getty Images News/Getty Images)

English associate professor Adrienne Brown explores the complicated racial history of the American skyscraper.

When the first skyscrapers soared into existence in the 1880s, Americans were fascinated by the new buildings on the block. Not everyone liked them, or believed the trend would last, but the towering structures—popularized in Chicago and New York, and exported worldwide—demanded attention. They changed the everyday lives of metropolitans, interrupting familiar skylines and packing bodies into the city more densely than ever before.

Even people living outside urban centers couldn’t escape the “mortared Himalayas,” as one writer dubbed them. Skyscrapers were ubiquitous in newspaper articles, cartoons, and photographs. Poets, including Carl Sandburg, wrote odes to them, and filmmakers cast them in starring roles. The silent-era classic Safety Last! (1923) features a set of death-defying skyscraper stunts. In one famous shot, actor and filmmaker Harold Lloyd dangles from a building’s edge clutching only the hands of a clock.

But despite their omnipresence in late 19th and early 20th century American life, there was one place where skyscrapers were hard to find: the novel.

Adrienne Brown was a graduate student at Princeton University when she first noticed the skyscraper’s curious absence from canonical novels about American cities. Skyscrapers got an occasional line or two (in The Great Gatsby [1925], for instance, they are likened to “white heaps and sugar lumps”) but were otherwise peripheral and unimportant to the story.

This indifference surprised Brown, now the director of undergraduate studies and an associate professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at UChicago. The skyscraper got fanfare “in almost every other cultural sphere. … There are plays written about it, there’s poetry about it, but the novel as a form is not that drawn to it.” Was it really not there, she wondered, or was she just looking in the wrong places?

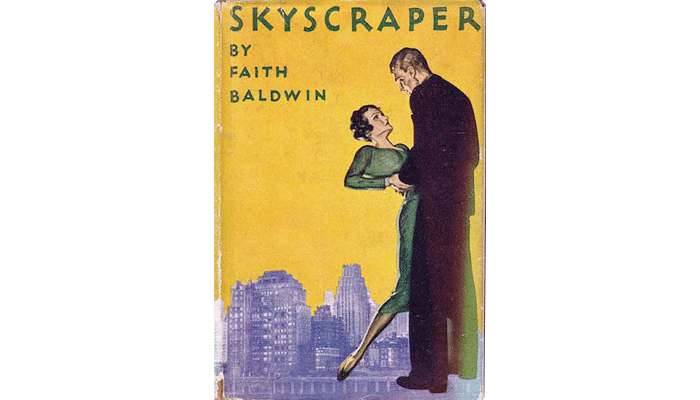

Answering that question led Brown to the pulpy edges of American literature. In dime novels, science fiction, romances, and so-called weird fiction, skyscrapers abounded. The more time she spent with these fantastical tales, as well as architectural writing and reportage from the era, Brown began to see how enmeshed their representations of the buildings were with post-Reconstruction racial anxiety in America. Those entanglements are the subject of her book The Black Skyscraper: Architecture and the Perception of Race (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017).

Skyscrapers didn’t just change city skylines. Brown argues that they also demanded people develop new ways of seeing and relating to others. And those new ways of seeing emerged at a historical moment when race was in flux as Americans debated how, precisely, to conceptualize race and make racial identifications. In The Black Skyscraper Brown writes that “the early skyscraper threatened to reveal the ‘nothingness’ of race … precisely when the nation most desired to assert and extend the meaningfulness of race.”

Brown grew up in suburban Maryland. Because of legal restrictions on the height of buildings, there are few skyscrapers in the nearest big city, Washington, DC. She doesn’t remember the first real skyscraper she saw. “No one was more surprised than me when the skyscraper ended up being at the center of [my] book,” she says.

But she was always fascinated by architecture and how we relate to it. (Any aspirations of being an architect herself were scuttled by a lack of depth perception and being overall “very bad spatially.”) As a University of Maryland undergraduate, she wrote her senior thesis on literature about the suburbs.

The idea of getting a PhD wasn’t on her radar. But a professor encouraged her to apply to graduate school, and she settled on Princeton, home to several scholars working on the intersection of architecture and literature, and strong programs in pure architecture and American studies. That’s when she began reading and writing about the skyscraper, which became the subject of her dissertation.

When she joined the UChicago faculty in 2011, Brown began the work of expanding her dissertation—which focused more narrowly on the skyscraper’s absence in early 20th century novels—into The Black Skyscraper. The buildings’ relationship to race grew from one chapter into the book’s primary focus as she noticed that “this question about the life of race, whether race could remain a viable category that you could read from the outside, was constantly shadowing the skyscraper.”

One challenge of writing the book was helping modern-day readers understand how radical a shift skyscrapers represented. The ability to perceive the world from above is something we take for granted today. We fly in airplanes; we own drones; we’ve seen the earth from space. But life in the 19th century was smaller in scale. Suddenly urban citizens had to adapt their bodies to a new architectural reality.

“You do find these stories in the ’10s and ’20s of people from Iowa arriving to New York and Chicago for the first time and having to crane their necks,” says Brown. “Their muscles hurt from having to look up all the time.”

That wasn’t the only adjustment skyscrapers necessitated. “People looked drastically different depending on where one stood in and around these tall structures,” Brown wrote in a 2017 blog post. From the top of a skyscraper, everyone became “an ant-like speck.” On the jam-packed streets below, faces were abstract and hard to see. In the new world created by the skyscraper, bodies took many forms: they looked one way from up close, another from on high, another from within a crowd.

This was a threatening shift in an era when lawmakers were trying to decide what made a person black or white, Brown contends. The one-drop rule, which stated that any amount of black ancestry made someone black, became law in many Southern states but had obvious limitations. In urban areas, you might not know your neighbor’s name, let alone their genealogical background.

In the North and the West, where migrants were plentiful but family history was scarce, appearance became the standard by default. You were black or white or Asian because you looked that way. In the 1920s the Supreme Court upheld this practice, arguing that race was “a matter of familiar observation and knowledge” that “the common man” could interpret.

But it was clear from Brown’s research for The Black Skyscraper that writers in the early 20th century were beginning to see how fragile a criterion appearance offered. White Americans wrote fearfully about the dangers of black Americans “passing” and intermarrying. Black writers grappled with the practice too, in novels such as Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929), about a black woman who has concealed her racial identity to marry a white man.

Much of Larsen’s novel takes place in and around skyscrapers—a choice that, Brown argues, serves to highlight the various ways city life complicated the act of racial perception. Through the tragic death of Passing’s protagonist, Larsen ultimately shows that the growing difficulty in pinning down a person’s race didn’t make the question go away. If anything, the desire to make racial determinations got stronger.

That theme carries through to other stories that Brown studies in The Black Skyscraper. Several, not coincidentally in Brown’s view, are science fiction or apocalypse narratives. “When you think about how crazy it was to people that these buildings were being put up, the science fiction already writes itself,” Brown says. If anything, the genre of science fiction “had to keep up with the buildings.” (Some of the stories feature the destruction of iconic skyscrapers, a cultural fascination that hasn’t gone anywhere: “We are still doing that with Transformers.”)

One structure, New York City’s Metropolitan Life Tower, is the setting for two very different apocalypse stories about race and the urban setting. George Allan England’s serialized epic The Last New Yorkers (1909) depicts the building under attack by a horde of monsters. From inside the structure, the story’s white protagonists identify the encroaching creatures as hybrids of apes and “degenerate” nonwhites who have returned to a “primeval state.”

Eleven years later, W. E. B. DuBois chose the same setting for his short story “The Comet” (1920), about the aftermath of a natural disaster. But in DuBois’s telling, the setting of the Metropolitan Life Tower allows Manhattan’s two remaining residents, a black man and a white woman, to acknowledge each other’s humanity. Looking out over the city below, the unnamed woman remarks on “how foolish our human distinctions seem—now.”

Could race be a human distinction that no longer matters? The question hangs in the air but doesn’t find an answer in “The Comet”: DuBois’s protagonists soon discover that only New York has been destroyed and the rest of the United States (and its racial regime) remains intact.

It wasn’t DuBois’s first time using the skyscraper as a motif—his earlier unpublished story “The Princess Steel” (c. 1908) is also set in one. In his work, “the skyscraper is putting forward these potentially liberatory conditions that disrupt the social script of racial domination and oppression and discrimination,” Brown says. The hopeful possibilities “often crash down eventually, but he does use the skyscraper to stage these ‘what-if’ moments.”

In the ’40s and ’50s, the suburbs replaced the city in the American cultural imagination. The housing developments springing up around the country were the new utopias and sites of fascination—at least for white families. Black families were largely kept out. Sometimes the discrimination was explicit: Levittowns, the iconic postwar developments in the Northeast, initially had a whites-only clause in their lease agreements. In other cases the government and banks enforced segregation through the practice of redlining, which de facto prevented residents of black neighborhoods from getting mortgages.

Since finishing The Black Skyscraper, Brown has also moved some of her research from the city to the suburbs. She’s at work on a new project about property ownership and midcentury white flight, and recently published an American Quarterly article examining real-estate appraisal manuals from the turn of the 20th century, in which questions about racial perception are once again front and center.

For Brown, studying redlining and property feels like the logical sequel to The Black Skyscraper. If cities complicated the existing order, “the suburbs become a longer-term answer to that question. … The suburbs are low rise, they’re removed from the city. You can have more control over who’s moving in and out,” Brown explains.

The issues are at once new and familiar: how architecture and race entwine, and how writers contend with those links. “It’s fun to be at the beginning of this new project that very much comes out of The Black Skyscraper but carries it forward.”

A fresh look at W. E. B. DuBois’s fiction

W. E. B. DuBois is known primarily for his nonfiction and his activism, but Brown got to know a different side of the legendary sociologist while researching The Black Skyscraper. She was drawn to DuBois’s short fiction, which includes not only science fiction, such as “The Comet,” but also romance, fantasy, and mystery. His stories have often been regarded as a footnote in his career, and not without reason. “The writing can sometimes be a little strange and hard to wrap your mind around,” Brown says.

But she believes DuBois’s fiction was more than strange. It’s where he began “testing out and thinking through some of the ideas that end up informing some of his social thought.” With Britt Rusert of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Brown is editing a forthcoming collection of DuBois’s fiction, much of it previously unpublished.

In gathering material for the book, Brown and Rusert have discovered a treasure trove of DuBois oddities in the archives at Fisk University, including a story about an electric car. They’ve also found Agatha Christie-esque parlor mysteries written under the pen name Bud Weisob (an anagram of his name).

They aren’t sure why he used a pseudonym. It may have been a political necessity—DuBois was blacklisted because of his ties to communism—or because the stories were “so strange that they were off brand.” Some, Brown thinks, could be explained by DuBois trying to advance his political agenda through a popular medium. “But some of them don’t necessarily fit into that, and those are the ones we’re interested in—where they don’t neatly fit into any kind of propagandist agenda. They’re just him writing a mystery story.”

“So you just never know what you’re going to get in the DuBois archive.”