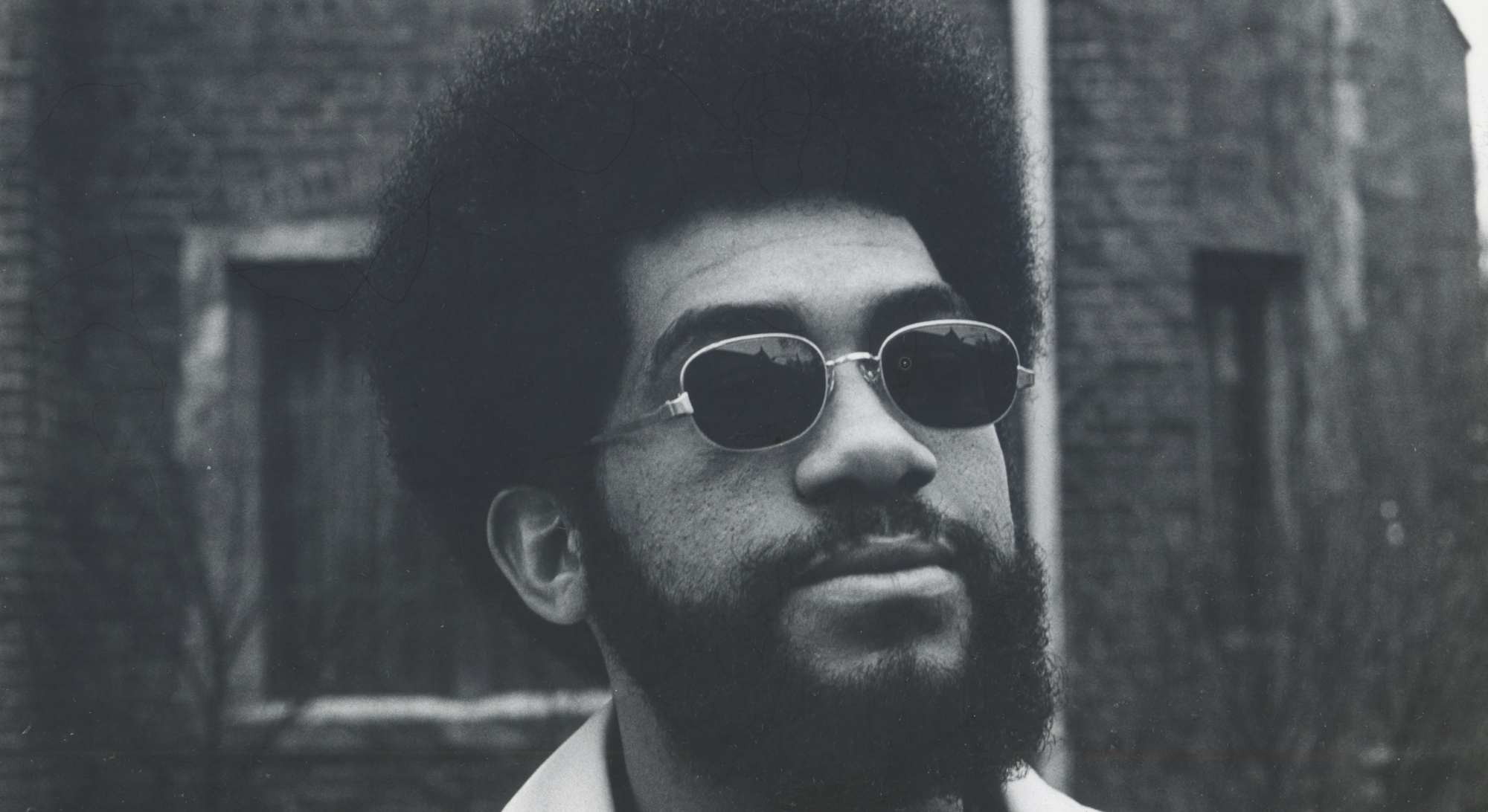

Alphine Jefferson, AB’73, in 1972. The photo was taken by Scott Campbell, AB’73, AM’75, MBA’81, his “first and only roommate,” when they ran into each other in front of Bartlett Gymnasium. (Photography by Scott Campbell, AB’73, AM’75, MBA’81, courtesy Alphine Jefferson, AB’73)

How Alphine Jefferson, AB’73, became an oral historian. As told to Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93.

At Alumni Weekend 2024, Alphine Jefferson, AB’73, stopped by the publications table while I happened to be staffing it. Noticing the degree year on his name tag, I asked if we could interview him for a feature I was planning for The Core—an oral history of the College in the 1970s (“Ho-Ho, the University of Chicago Is Funnier Than You Think,” Spring/25).

Only later did I realize I had accidentally buttonholed an eminent oral historian. Jefferson has taught at Southern Methodist University (where he was recognized with the Most Popular Professor Award), the College of Wooster, and Randolph-Macon College, among others. He retired in 2022. His current projects include an essay on novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, whom Jefferson calls “America’s first Black oral historian.”—Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

I stuttered severely until I had a faith healing in my Pentecostal church when I was 15 and a half. As a result of stuttering, I have always paid attention to language—people’s accents, their speech patterns, and their grammar.

My introduction to oral history, as we call it now, was listening to the stories that people told. My parents were the second family in our area to get electricity. Most people had no electricity. So obviously, there was no TV. There was no radio.

But my interest in oral history actually began on December 4, 1969, when [Black Panthers] Mark Clark and Fred Hampton were assassinated in North Lawndale. Judy Mitchell-Davis [AB’73], who was from North Lawndale, took me in her car to her sister Edna’s restaurant—Edna’s famous restaurant where Martin Luther King Jr. had set up his open-housing campaign—and she introduced me to Timuel Black [AM’54, author of Bridges of Memory, a two-volume oral history on the Great Migration]. He and I talked that night.

I’m sure he realized that he could best get the story of Black Chicago by talking to people. I remember running into him one time at Valois on 53rd Street. I could barely get in because everybody’s sitting around the table with Timuel Black.

After graduation I attended the brand-new Duke University Oral History Program, the first PhD program in oral history in the country. They aggressively recruited me.

The very first academic oral history program had been established in 1948 at Columbia University by Allan Nevins. He interviewed only politicians: governors, senators, and presidents. It was a great white men oral history program. He wanted to capture those rare moments when someone made that one unguarded remark.

So I went to Duke in 1973. In the summer of 1974, I was chosen to coordinate a group of eight Duke students, Black and white, to interview Black farmers who were losing their land throughout the South.

Two of us drove to Montgomery, Alabama. At the hotel reception desk, we told them we were Duke students who had reserved rooms for our oral history work. And the guy said, “Oh. We do not have a reservation for you.” So we said, “If we have to call Duke University and say there are no rooms for us, you are probably going to have some problems. Do you want us to make that call?” So they gave us one room. We had to share.

The people at Duke had trained us—when you’re in a community that you do not know—to go to the barber shop, the beauty shop, or the post office. Introduce yourself, tell them who you are and why you’re there, to establish credibility.

So I went to the post office. It happened to be a Black postal worker, male. I told him I was going to interview Charles Johnson. He looked at me with horror and said, “Which Charles Johnson? The Black Charles Johnson, or the white Charles Johnson? Because the white Charles Johnson just shot a Black man to death last week who walked up and knocked on his front door.” That is a true story.

We asked farmers about losing their land, about how they were denied loans. And it was just a sad story. In the year 1900 Black Americans owned 25 million acres of land. Right now, it’s less than 1 million.

The best way to get someone to talk to you is to find that point of commonality. So I would talk about being a church boy. The family would invite me in. One of the interviews I did, the guy had no time for me, but he said, “If you ride on the back of this tractor, I’ll talk to you.” That is a true story.

My dissertation was on housing discrimination in North Lawndale. Obviously, I was the outsider. I’m from Virginia. People have all these stereotypes about Southerners.

There’s a longtime rivalry between Black Americans on the South Side of Chicago and on the West Side. People from the South Side were supposedly more sophisticated, educated, and bourgeois. People from the West Side were directly from Mississippi’s cotton fields and were less sophisticated. I was intrigued by that dichotomy.

Timuel Black introduced me to some of the elders of the North Lawndale community. I was interviewing this woman, and she said, “Boy, you don’t understand the protection you have.” I said, “What do you mean?” She said, “It has gone out to the gang members not to bother the guy with the white-over-blue Chevy Malibu with the North Carolina plates. Do not bother that boy, because he is doing good work.”

I’ve always been fascinated by the color line. What has amazed me is the extent to which people’s stories are grounded in their ability to negotiate the contradictions in their own lives.