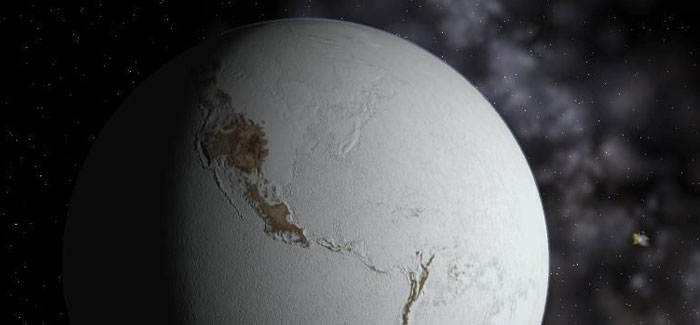

Why wasn’t early Earth encased in ice? (Illustration by neethis/celestiamotherlode.net)

Researchers find higher-level thinking in four-year-olds, chronicle anti-Judaism as a foundational idea in Western thought, parse the the hidden messages in praise for children, and answer a geological mystery: why wasn’t paleo-Earth encased in ice?

Higher learning

Children as young as four and a half show signs of higher-level thinking skills, says Lindsey Richland, assistant professor of comparative human development. Examining data from a longitudinal study of children from birth through age 15, Richland found a link between executive function—the ability to plan, switch tasks, and control attention—and the development of complicated analytical reasoning. Along with strong vocabularies, children’s ability at four and a half to monitor and govern their responses to stimuli predicted higher scores on written analogy tests when the children were 15. With a coauthor from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Richland published her findings in the January Psychological Science.

Jews and the West

Tracing Western thought from antiquity into the 20th century, medieval historian David Nirenberg argues in Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (W. W. Norton, 2013) that anti-Judaism is a foundational part of Western thought, not an idea confined to its ideological extremes. Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans; Christians and Muslims of every period; and contemporary secularists have used Judaism, he writes, in constructing their visions of the world. They relied less on direct knowledge of real Jews (many thinkers would not have known any) than on “figural Jews” who stood in for everything they opposed. For example, Martin Luther condemned the Catholic Church for what he called its “Jewish” tendencies, while his adversaries accused the Jews of using him to weaken the church.

Attaboy

It’s better to praise children for what they’ve done than for who they are. According to a study by UChicago researchers, congratulating children for working hard or doing well motivates them to work even harder and do even better, by sending the message that effort and action lead to success. Simply telling children that they are good or smart, however, sends the message that their abilities are fixed, and they respond with decreased persistence and performance. Collaborating with Stanford researchers, Elizabeth Gunderson, PhD’12, now at Temple University, and Chicago psychology professors Susan Goldin-Meadow and Susan Levine videotaped family interactions of children between one and three years of age, classifying their parents’ praise. Following up with the same children five years later, the researchers found that those who were praised more for their efforts than their abilities were better at handling challenging tasks and responding to setbacks, and that they were more likely to believe that intelligence and personality can be developed and improved. The findings were published online in Child Development in February.

A paleo-greenhouse effect

Early Earth should have been one giant snowball. For the first two billion years of the planet’s existence, the sun—itself a young star then—gave off only a quarter of the light it now emits. But geological evidence shows that the earth was not encased in ice; there were oceans and rain and undersea volcanoes. How? In the January 4 Science, Chicago geophysicist Raymond Pierrehumbert and geophysical sciences postdoc Robin Wordsworth argue that greenhouse gases kept the earth warm. Not carbon dioxide, which wasn’t abundant then, but hydrogen and nitrogen. Those molecules don’t normally absorb much sunlight, but collisions between them could have produced chemical energy that caused them to absorb infrared light. Modeling early Earth, Pierrehumbert and Wordsworth found that “collision-induced absorption” may have raised Earth’s temperature by as much as 60 degrees Fahrenheit, enough to keep its water from freezing.