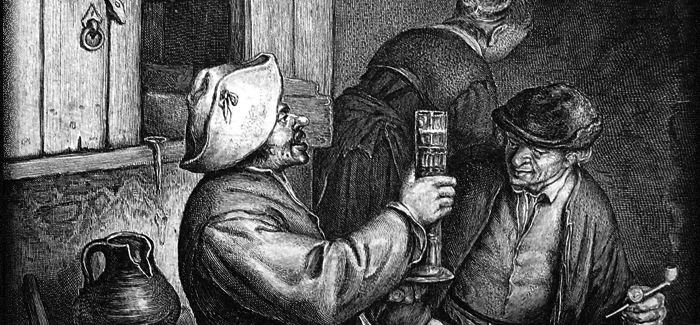

A museum engraving shows an inn, a center for social and business life, for Pilgrims as well as other townspeople. (Image courtesy Jeremy Bangs, X’67)

In one of the oldest chapters of American history—the Pilgrims’ flight from persecution—historian Jeremy Bangs, EX’67, finds new ground to cover.

The Dutch town of Leiden, 25 miles south of Amsterdam, is home to a strange little museum. Occupying the intersection of Beschuitsteeg and Nieuwstraat, where the cobblestones dead-end into the Gothic enormity of the Hooglandse Kerk—one of several monumental churches that share the skyline with the town’s windmills—the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum doesn’t seem much like a museum at all, not in the usual sense. There are no display cases, no guidebooks, no labels explaining the artifacts. Instead, there’s a small square room in a 14th-century building, dimly lit by candles and casually inhabited by furniture and paintings and other appurtenances hundreds of years old: goblets, candlesticks, leather-bound books. A brass bed warmer hangs on the wall beside a medieval built-in bed; a baby’s crib sits on rockers beside the painted-tile fireplace. Everything is nonchalantly, unceremoniously just … there. The only nod toward ordinary museum convention is an easel at the back holding a dozen or so placards densely printed with historical information, which some visitors gamely try to read before moving on to the maps and engravings.

Occasionally people come in thinking this must be a shop. Others see the leaded windows and dark interior and walk in hoping to order a beer. But most of the visitors who come to the museum, about 2,000 a year, are tourists. They don’t necessarily know what they’re in for. You can see them trying to get their bearings as soon as they cross the threshold. What they inevitably discover is that the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum is, most essentially, its proprietor: Jeremy Dupertuis Bangs.

Bangs, EX’67, is perhaps the foremost living scholar of the Pilgrims. “One of the best I’ve ever come across,” says New England genealogist Robert Charles Anderson. He’s also one of the few serious scholars left who studies the Pilgrims. Yes, Bangs says, those Pilgrims, the ones with the first Thanksgiving, the ones we think we know so well already, whom history has alternately celebrated and castigated, without ever really getting it right. Before they boarded the Mayflower in 1620—the first of several ships carrying Pilgrims to Massachusetts—the English Calvinists spent more than a decade as refugees in Leiden, a university town known now for its beautiful canals and sprawling street market, but in the 17th century for religious tolerance and a robust textile industry. Leiden was an important haven for the Pilgrims; it sheltered them and shaped them. The concept of civil marriage, which the Pilgrims brought with them to America, planting an early seed of the separation of church and state, is taken from Dutch law. Explicating the concept, Plymouth Colony governor William Bradford quoted in his journal a passage from a book on Dutch history. In the museum, Bangs has a copy of the very same edition: A General History of the Netherlands, printed in 1608. In his journal, Bradford referred to page 1029; Bangs opens his own book to page 1029 and reads: “‘It was decreed by a public proclamation, that all such as were not of the Reformed religion, (after lawful and open publication) coming before the magistrates in the townhouses, were orderly given in marriage one unto another.’” He looks up. “So, that paragraph is a source for the beginning of civil marriage in English law.”

Even that first Thanksgiving has Dutch roots, Bangs says. It drew not only on biblical harvest festivals but also on the thanksgivings the Pilgrims attended every October 3 in Leiden, commemorating the end of the Spanish siege of 1574, in which half the town’s population died. “An obvious parallel,” he wrote in one essay, to the Pilgrims’ brutal first winter in Plymouth after their voyage across the Atlantic.

Bangs made the reverse journey. Born in Oregon and raised mostly in and around Chicago, he has spent the majority of his adult life in Leiden, amassing vast and formidable expertise that includes but isn’t limited to the Pilgrims. He’s written and edited half a dozen books on the Pilgrims, one of which, Strangers and Pilgrims, Travellers and Sojourners (General Society of Mayflower Descendents, 2009), chronicles their Leiden experience.

But he’s also written about Reformation-era theology, architecture, and art history. His dissertation, written at Leiden University, is on 16th-century Dutch tapestry weaving and church furnishings. In high school, Bangs was a good enough bassoonist to be accepted to Juilliard without applying (he didn’t go), and he first arrived in Leiden as a 22-year-old working artist, three courses shy of a college degree from the University. “What makes Jeremy so special,” says Anderson,“is that he has such a broad—I mean, he’s an art historian, he’s an architectural historian, he knows the theology, and he knows the languages and the history behind all of it.” A onetime biochemist who took a break from the lab in 1976 and never went back, Anderson got interested in genealogy after a great aunt died, leaving behind a family Bible with some unknown names and birthplaces. Now he directs the Great Migration Study Project, an effort to catalogue every single emigrant who settled in New England between 1620 and 1640. It’s close work and, after 25 years, only half finished. “We’ve batted stuff back and forth over decades now,” he says.

Now 67, Bangs seems to remember everything he’s ever read. He walks with a slight limp and carries a cane, a result of the multiple sclerosis he was diagnosed with almost 20 years ago. But it doesn’t keep him from hopping up onto a chair or a bench to show off a high-hung painting or to grab an artifact he thinks a visitor might like to see. When his jokes aren’t corny—“some of the oldest things in the collection are my jokes,” he says—they are wry and acerbic, and punctuated with an almost inaudible chuckle. The longer you talk to him, though, the more his reserve unwinds into a kind of guarded warmth. And at all times, he radiates the coiled patience of someone who knows the answer to most any question you might ask and is just waiting for you to ask it. “He knows everything,” says Sandra Perot, a PhD student from Massachusetts who interned with Bangs at the museum this past summer. “With Jeremy, part of it is wanting to know what you want to know about the story.”

Bangs’s father was Carl Bangs, PhD’58, a church historian and theology professor, and an expert on the 16th-century Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius. Carl Bangs’s 1985 biography, Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation (Abingdon Press), is a definitive text. “I grew up expected to contribute at a rational level to dinner conversations, or else not talk,” Bangs said. He did some of both. One night, he recalls, UChicago philosopher Charles Hartshorne was over for dinner. “I was very small, probably second grade.” A recent trip to the Field Museum of Natural History had deeply impressed him, and after dinner he asked Hartshorne if he’d like to see his bug collection. Then, to the embarrassment of his parents, Bangs brought out the dozens of cockroaches he’d been collecting from the basement, carefully squashed and glued to three-by-five cards, which he labeled, “bug 1,” “bug 2,” “bug 3,” and so on. A philosopher interested in the metaphysics of “becoming” rather than “being,” Hartshorne asked whether it might be better to study the roaches where they lived instead of as static corpses. “So,” Bangs says, “that’s what it was like growing up.”

At Chicago, Bangs studied art—painting and drawing, building on the landscapes and portraits he’d done since childhood, plus lithography and sculpture—and double majored in art history. He took a year or so off, and by 1968 he still needed three core classes: math, biology, and physics. “I came back that summer and saw a bunch of my friends get beaten up by the cops in the riots, and I said, no, I’m not going to stay,” Bangs recalls. “I’ll just go off and be an artist.” After a sojourn in London, where he got exhibits but a museum job fell through, Bangs came to Leiden, where his father was a visiting professor. He was running out of money and losing direction. “And my father’s friend said, ‘Look, kid, go back to school.’” So he did, in Leiden. Although he’d never spoken a word of Dutch, Bangs knew how to read it—17th-century Dutch, anyway. He’d learned it in high school when his father drafted him as a research assistant translating theological texts. He picked up modern Dutch once he got to the Netherlands. “Although apparently,” he says with an offhanded wave, “my vocabulary still includes antiquated words.”

At Leiden University, finishing up his college degree turned into graduate school, which turned into graduate research and trips to the municipal archives. Leiden’s archives contain a nearly complete record of the town’s existence going all the way back to the Middle Ages: receipts, certificates, licenses, contracts, births, deaths, marriages. It was an almost bottomless pool of knowledge. Bangs had sensed its depth, but he didn’t yet know how to swim it. “I needed to be able to read the documents,” he says. Few people can, or ever have. It’s not simply a matter of knowing old Dutch; the records are written in script indecipherable to those not trained to recognize the shapes of letters in antique handwriting, the obscure abbreviations, the archaic grammar. An archivist named Bouke Leverland took notice of Bangs and began tutoring him in paleography, helping him transcribe old records into readable documents.

A whole world opened then. A priest in the Old Catholic Church, which split from Rome in the 18th century, Leverland was a scholar of the Middle Ages and a brilliant man, Bangs says. “But he was such a perfectionist. He could have gotten his doctorate, but he could never decide when he was finished.” After he died, some of Leverland’s former students compiled a book from his notes and published it. “It would easily at any time in the previous years have been accepted as a dissertation.”

Getting his own PhD in 1976, Bangs started work as a historian in the Leiden archives in 1980. Immediately, and involuntarily, he became its Pilgrim specialist. “They said, ‘You’re an American, what do you know about the Pilgrims?’ And I said, ‘Nothing. Life’s been OK without it.’ And they said, ‘Too bad; you now do that as well.’” This is a story Bangs tells often, adding that his bosses warned him not to bother with additional research on the Pilgrims: “It’s all been done.”

Except it hadn’t. After 15 minutes in the archives, Bangs says, he turned up a document no one had known was there: a rent dispute in which a Leiden landlord was complaining that a Pilgrim hadn’t paid his rent on time. A small thing, but a sign, he thought, of more. Bangs started reading everything in the archives up through 1630, and some records through 1700. Increasingly, he became convinced that the prevailing narrative about the Pilgrims—that they were rigid and intolerant, and in the long run insignificant, that they wanted religious freedom for themselves only—was untrue. “For one thing, they were considerably more tolerant,” he says. “They were attempting to get their own religious beliefs right, but because of the way they read the Genesis story of the Fall, if everything after it is imperfect, so is theology, every theology, including your own assessment of somebody else’s.” Bangs swam deeper. On the subject of Pilgrim courtship, he found an insight in 17th-century Dutch poet Jacob Cats, who wrote poetry in English that reflected Dutch Reform attitudes,“which the Pilgrims shared,” he says. “We know this from advice that their minister gave.” Cats’s poems warned young people against being too bashful, Bangs says. “‘You’re not going to get any response if you don’t say anything,’ for example. And in another one, there’s a comment that even if the girl’s apron has been shifted already, she might be a very nice person. These are not things you’d expect.”

In 1986, Bangs took a job in Massachusetts as chief curator at Plimoth Plantation, a re-creation of the Pilgrims’ Plymouth Colony, then at the archives in nearby Scituate and then at Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth. “You know, when I first started, I wasn’t expecting the Pilgrims to be particularly interesting,” he says. “It turned out to be rather a different story.” He began transcribing 17th-century records the Pilgrims had left behind in American archives, a massive project that remains unfinished—a box of photocopied records from Plymouth Colony sits under a table in the museum in Leiden. Looking into the Pilgrims’ dealings with the local Indian tribes, he found that there, too, many historians had gotten things wrong. Deeds for the land the natives sold to the Pilgrims showed an attempt at fairness, says Bangs, who in 2002 published Indian Deeds: Land Transactions in Plymouth Colony, 1620–1691 (New England Historic Genealogical Society). “They believed that since the Indians had signed agreements to be subjects of the king, they deserved equal treatment in English law.” A study of horses’ earmarks, which owners used to identify their animals, revealed that Pilgrims in Eastham regularly sold the horses they bred to the natives. “Which points to a relatively peaceful ability to live together,” Bangs says. In fact, he adds, looking at Eastham’s records “it’s possible to say that the majority of people living in the town throughout the entire 17th century are the Indians. Nobody’s ever noticed that.”

After a decade, Bangs was ready to get back to the Netherlands. He wanted to open his own museum. So in 1996, he and his wife, artist Tommie Flynn, whom he met in Massachusetts, moved to Leiden. It was late fall and the roses were still blooming. They set up house temporarily in a floating cinderblock of a houseboat. During his earlier years in Leiden, he’d become part of the culture there, Flynn says. “I don’t think he ever quite acclimated when he came back to the US.” On Thanksgiving Day 1997, the Leiden American Pilgrim Museum opened in the ground floor of the oldest known house in town, built around 1370.

On a gluey hot afternoon in early September, Pat and Art, an American couple originally from New Jersey, stopped by the museum, gingerly pushing open the door and stepping into the cool, shadowy indoors. Like a lot of the museum’s visitors, they have Pilgrim ancestry and an ardent interest in New England’s first colonists. Pat came with a handwritten piece of paper tracing her family back to Pilgrim leader William Brewster. Bangs offered them the easel of densely printed placards; he gave his customary spiel about the museum and the house, how it was originally built as a residence for priests at the Hooglandse Kerk next door, and how, after the Reformation, it was rented to ordinary families. No Pilgrims ever lived in the house, although Brewster came there in 1609, just weeks after the Pilgrims’ arrival in Leiden, to make arrangements for burying one of his children—probably an infant, Bangs notes, because the archives have no record of a name or an age. Bangs took Pat and Art’s admission fee—four euros each—and told a joke about the 402-year-old church poor box he uses as a cash register: “It’s designed rather like Calvinist theology,” he said, turning it upside down as the coins inside it jangled. “No matter how much you put in it, not much comes out.” Pat and Art looked around the room; they tried to get their bearings. There were long moments when nobody said anything.

Then they started asking questions. And then Bangs was telling stories, opening drawers of Pilgrim-made tobacco pipes and cloth seals evoking their work as weavers, wool combers, carders, and cloth fullers in Leiden’s textile guild. Bangs showed off his collection of centuries-old spoons—wooden, pewter, brass, and one drilled with holes for straining sugar—and children’s pottery and toys. He pulled out an elegantly carved folding table and a beat-up wooden candleholder, both exceedingly rare. In the museum’s second room, which Bangs calls “the medieval room,” because it retains its original 14th-century floor and fireplace and is decorated with furnishings from the Middle Ages, Art sat in a chair from 1200 and played with a set of jacks made from cow knuckles. Bangs gave a lengthy explication of a 500-year-old linen banner depicting symbolic moments in the Crucifixion: the agony at Gethsemane, Pilate washing his hands, soldiers playing rock-paper-scissors for Christ’s robe.

Back in the Pilgrim room, Art spotted a large wooden and metal contraption that looked like a jack. “The great screw,” Bangs said grandly. “William Bradford, writing about the journey across on the Mayflower, mentions a storm in which the main beam of the Mayflower broke. And luckily one of the passengers had a ‘great iron screw.’ And with that they were able to jack up the main beam and support the mast and continue.” For decades historians were baffled—what was this great screw? A 1920 book suggested that perhaps it was part of a printing press the Pilgrims brought with them. Many of them had worked in printing houses in Leiden, and Brewster ran a clandestine operation publishing books forbidden in England. But there’s no evidence, Bangs says, that the Pilgrims brought a press with them to the New World. The mystery remained.

Then last year he happened across a reference to a great screw in a 17th-century guide to house carpentry. It described a tool standing about three feet high that worked much like a car jack. By coincidence, his friend had been looking for the very same tool, though he didn’t know its name, to lift the museum building’s roof and replace a structural beam. “So we got one,” Bangs says. The great screw saved his friend the trouble of hiring a crane and blocking off the street. And now, Bangs says, “it’s a pretty nice little addition to the museum’s collection.” As Art and Pat watched, Bangs leaned down and turned a crank. The great screw opened, clanking loudly.

“I encouraged him always to bring out the treasures,” says Perot. A graduate student in early American history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Perot and her daughter Zoe, a sophomore at Princeton, interned with Bangs this past summer. He tutored Zoe in paleography, while Sandra studied 17th-century furniture. “He has so many little gems all over the museum, and he can tell stories and stories about them. You can pick up glass beads that were manufactured in 17th-century Amsterdam, the type that were used for trade with the native population in the colonies.” That tactile experience is one of the best things about the museum, she says. “It helps people understand. What does it feel like when you put these things in your hand? How much do they weigh? When you actually hold a string of the beads, you can understand why the natives would like something like this. They’re pretty, they’re iridescent, they’re weighty.” And everything in the museum is real: the cooper’s mug, the tobacco pipes, the books. “It just gives you a better sense of humanity.”

Many, if not most, of the museum’s artifacts come from one man: antique dealer Ron Meerman, Bangs’s friend, landlord, and coconspirator. It was he who procured the great screw and used it to fix the roof. With his wife, Thea Koppenaal, Meerman owns the building; the couple live upstairs from the museum and run an antique shop around the corner. Tall and slight, with a graying blond beard and a kinetic expressiveness, Meerman has a knack for finding impossible-to-find things. It’s almost a refrain for Bangs, showing off an artifact, to say something like, “Only three examples of this were known. Now there are four.” Sometimes unexpected oddities like the great screw fall into Meerman’s hands. This past winter, as Bangs was giving a tour of the museum, Meerman came in holding a narrow, smoothly polished stick, which had just been dug up a couple of towns over, along with several other objects from the 1600s. “Look at this crazy little walking stick!” he exclaimed to Bangs in Dutch, as the two began to pore over it together. The walking stick now rests in a corner of the museum.

Meerman and Bangs first met more than 20 years ago, when Bangs was in Leiden on a purchasing trip for Plimoth Plantation and Meerman was just setting up his business. Bangs returned to Massachusetts with armloads of antiques. The two met again after Bangs moved back in 1996. Walking his dogs one day, Bangs came across a 16th-century door and door frame tossed out on the street. “These kinds of things happen in Leiden,” Meerman says with a rueful laugh. “Modernizing.” Bangs couldn’t carry the whole thing, so he picked up the frame and walked home with two dogs on leashes and a 400-year-old door frame around his neck. When he came back for the door, it was gone. A few weeks later he spotted it, leaning against a wall in Meerman’s shop. They hadn’t spoken in years, and, focused on the merchandise, Bangs hadn’t even realized the shop was Meerman’s. They reunited over lunch, and Bangs gave Meerman the door frame.

While he was looking for a place to put his museum, Meerman and Koppenaal had been looking for a way to open part of their house to the public. The arrangement seemed right. “It feels that the building is respected,” Koppenaal says. A less monumental structure than some of Leiden’s other landmarks, the house is no less worthy of saving, no less rich with history. “Jeremy is the storyteller,” she says. And the house “tells the story of itself as well.”

In truth, all of Leiden is Bangs’s museum. Walking the cobblestones with him, it’s impossible not to see how fluently and thoroughly he is a part of this place: the interlocking canals, the ancient Roman roads, the majestic city hall, where Pilgrims went to register their marriages. The cheap market across the street, where those who could afford meat would buy liver, tripe, and kidneys. The Pieterskerk, in the heart of the Pilgrims' neighborhood, which bears a memorial to their minister, John Robinson. When the Mayflower departed in 1620, only the first of several ships carrying Pilgrims to the New World, Robinson stayed behind with the rest of his congregation, waiting for a later trip. He died five years later, still in Leiden.

Many of the town’s Pilgrim sites are gone now, torn down to make room for the modernizing Meerman mentions. One of the last Pilgrim houses, William Bradford’s, vanished in the mid-1980s. Over the years, Bangs has been a nuisance to developers and city officials seeking to tear down much of the old part of town, including his own home, a narrow shank of a house built in the 16th century, which he and Flynn share with three pet rats and Joris Draak (“George Dragon”), a blind and deaf dog, who waits under the table for Bangs to feed him bits of cracker.

When he isn’t fighting off bulldozers or showing tourists around the museum, Bangs continues transcribing the Plymouth Colony archives. After 20 years’ labor, he’s got another five or six years to go, and now he’s looking for the funding to finish. During the 19th century, there was an effort to do this same transcribing, but it was interrupted by the Civil War. “They never got back to it,” he says. In the records, he’s hoping to find what happened to Plymouth Colony, how it all ended. “What causes it to disperse to the point where, in 1692, people were satisfied to lose the unity of the colony altogether?” That answer, he says, isn’t known. He’s swimming again.

Updated 11.26.2013 to reflect corrections noted in Letters (Jan–Feb/14).