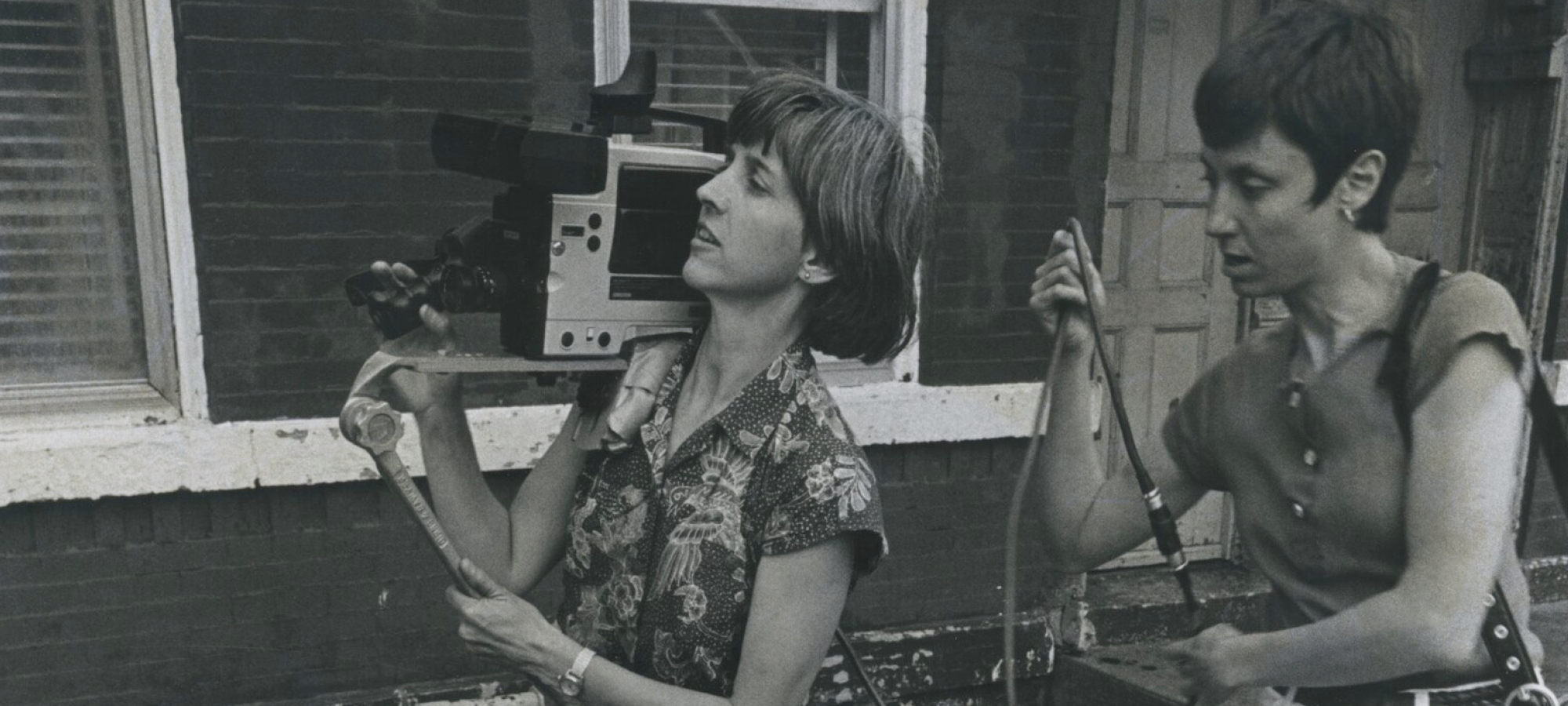

Guerrilla television pioneers Eleanor Boyer and Karen Peugh filming in Chicago in 1979. Footage from the movement urgently needs restoration. (Photography by Wayne Boyer)

Chicago’s Media Burn Archive is preserving a precious but vulnerable resource: video.

The revolution may not have been televised, but in the 1960s and ’70s, some of it was captured on tape by members of the guerrilla television movement, a loose conglomeration of filmmakers and activists who used new technology to tell stories not seen on the corporate television networks of that era.

The movement’s videographers turned their lenses on strikes, protests, and political conventions, as well as on everyday life in overlooked communities around the United States. Guerrilla television put cameras in the hands of ordinary people and allowed them to control the narrative.

Now this historically vital footage is at risk: videotape is a vulnerable medium, destined to degrade and, in some cases, to take with it events otherwise unremembered. Enter Chicago’s Media Burn Archive, a nonprofit whose mission is to collect and digitize important archival videos.

Fifty-year-old tapes are “very much at the end of their life span, and unlike film, you cannot bring them back,” says Sara Chapman, AB’04, the executive director of Media Burn. “It’s basically just a race against time to transfer them before they’re lost.”

The archivists are gaining ground in that race, thanks to a grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources. In partnership with UChicago, Media Burn will digitize more than 1,000 tapes associated with the guerrilla television movement. Duties are divided: Media Burn will convert the videos, and the University will catalog them and create an online archive.

The added tapes will bolster the singular trove of more than 8,000 videos Media Burn has converted and released since its establishment in 2003: everything from several hundred videos featuring Louis “Studs” Terkel, PhB’32, JD’34, to five minutes of B-roll footage inside the factory where Ms. Pac-Man was manufactured.

Media Burn’s interest in preserving guerrilla television footage isn’t new—about half of the nonprofit’s collection was donated by its founder, Tom Weinberg, one of the movement’s most prominent figures in Chicago—but the grant will give the digitization effort more momentum and visibility.

Broader awareness of guerrilla television has been a goal of Chapman’s since her time at the College. Originally a physics and astrophysics major, she took an elective class in documentary film with filmmaker and professor of practice in the arts Judy Hoffman.

Two weeks in, Chapman switched her major to Cinema and Media Studies, motivated by Hoffman’s teaching about guerrilla television and a classroom visit by Weinberg. After graduation she went to work for Media Burn, where she’s been ever since, rising to become its executive director in 2009.

“The thing that surprised me was that I had never heard of [guerrilla television], and my parents, who lived through the era—they’d never heard of it,” Chapman says. “Barely anyone knew that this really cool thing had happened.”

Guerrilla television arose from two simultaneous forces: the social upheaval of the ’60s and the rise of affordable recording equipment. Hoffman, a veteran of the movement herself, describes it as “a utopian moment” involving “a diverse group of people who were questioning society and authority.”

It couldn’t have happened without Sony’s portapak. While not nearly as sleek as an iPhone, the portapak (appropriate to its time) was revolutionary. It allowed its users to film and replay on the fly, as well as to do basic in-camera editing. Speaking by Zoom, Hoffman holds a portapak up to her computer’s camera. Designed in the late ’60s, it absolutely looks like it was designed in the late ’60s, with a portable videotape recorder connected to a small square box with a pistol grip—the video camera.

These features made it possible to “produce something immediately,” Hoffman says. “You can really be part of a struggle as it’s happening, rather than documenting something that happened in the past.” Amateurism lent authenticity as well. “It was OK if we were in the tapes, it was OK if the microphone was in, it was OK if we had a point of view. We didn’t need to pretend towards any kind of false objectivity. So it was guerrilla.”

But the imperfections also made the movement’s work easy to overlook. “Video is often a denigrated medium—much of this material was never taken seriously at the time,” says Daniel Morgan, PhD’07, professor and chair of the Department of Cinema and Media Studies, who worked with Media Burn on the Council on Library and Information Resources grant. “It wasn’t preserved. It wasn’t archived. It wasn’t restored. And so much of the work that we’re trying to preserve here has never been seen since the moment it was shot, or since the time it was first screened. It forms a kind of amazing record of the American democratic ethos.”

What emerges is an entirely different view of the world than mainstream news portrayed. “We have an incredibly detailed and personal history, especially of Chicago neighborhoods,” Chapman says. Then, as now, South Side and West Side neighborhoods were often portrayed only as bastions of gang and criminal activity. But guerrilla television footage shows other sides of life: community organizers at work, long conversations in hair salons, children sharing what they love about their neighborhoods.

With guerrilla footage, it’s possible to witness people long dead, places long demolished, and events long past in ways that words alone can’t always capture. It’s a vital resource for researchers and the public, Chapman believes. “We are only beginning to understand how important moving image media is for studying history.”