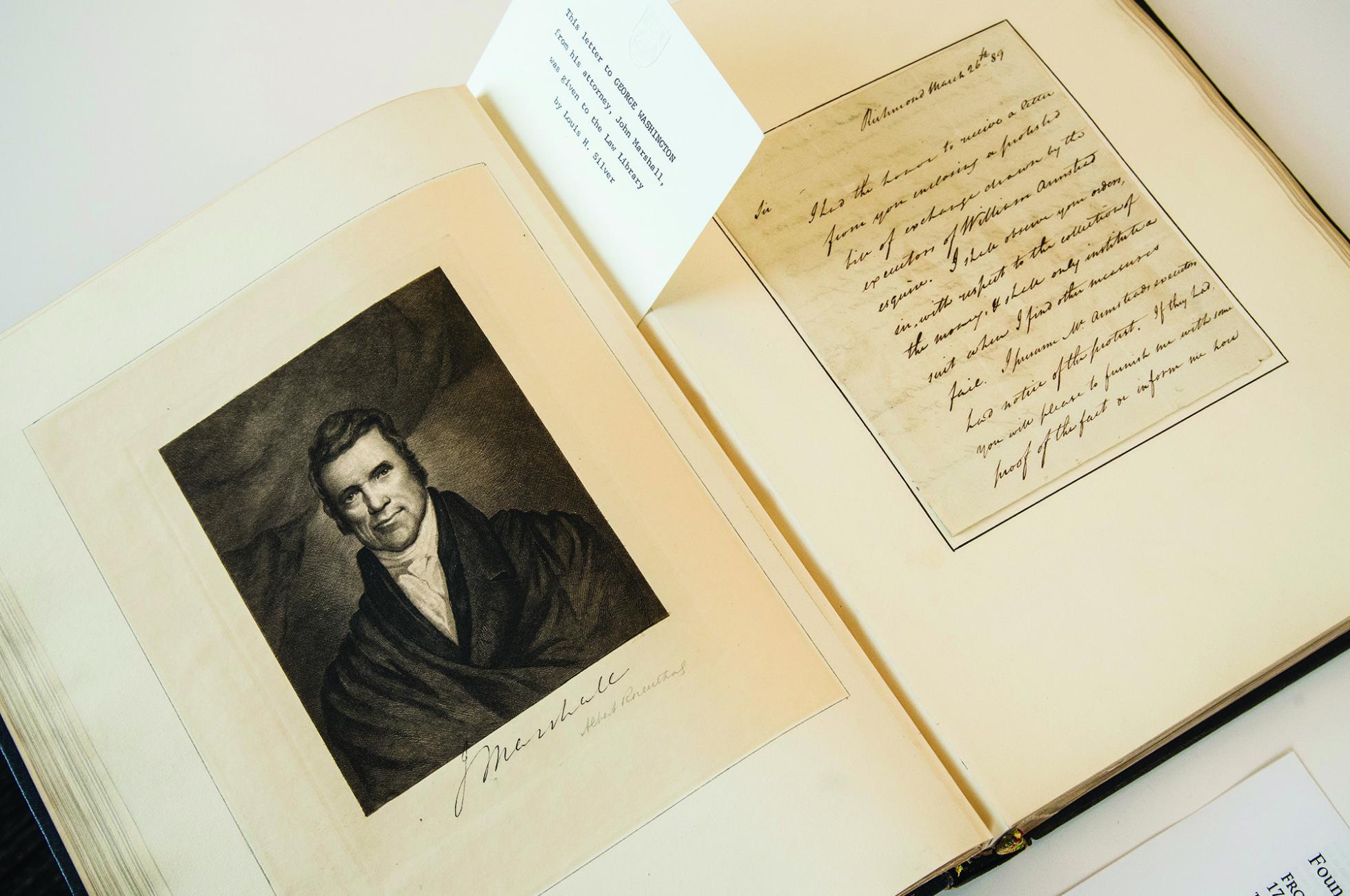

A letter from from John Marshall, later the chief justice of the Supreme Court, to George Washington was rediscovered in the Law School’s rare books collection. (Photography by Lloyd Degrane)

How a Law School librarian rediscovered a letter from John Marshall to George Washington.

In the late 1950s, hotelier Louis H. Silver, JD’28, made a donation to the Law School of rare items about and belonging to early Supreme Court justices. The letters, portraits, and legal documents from figures including Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Jay were carefully tucked away in the Law School’s rare books collection, where their existence gradually faded from institutional memory—a not uncommon fate in the era before digital library records.

Almost 60 years later, Sheri Lewis, director of the D’Angelo Law Library, rediscovered the Silver collection after seeing it referenced in a 1958 article in the University of Chicago Law School Record. She had a hunch the collection was important, but what she found in it still surprised her. Among the 75 letters was one from John Marshall, later the chief justice of the Supreme Court, to George Washington. Although its contents are relatively mundane—Marshall was representing Washington in a dispute over a piece of land on the Ohio River and wrote with an update—the letter was sent 22 days after the ratification of the new Constitution, as Washington waited for the final results of the first presidential election.

While scholars were aware from other records of a March 26, 1789, letter from Marshall to Washington, no one knew what had happened to it or what it said. Alison LaCroix, the Robert Newton Reid Professor of Law and a specialist in early legal history, was among the first to see the note after it resurfaced. It’s a peek at Washington’s daily life as he was preparing “to be the chief magistrate of this unknown experiment,” she says. The letter’s loss and rediscovery are a reminder of how much our historical knowledge is shaped by what evidence survived. “There’s always this question of what has been preserved and why it’s been preserved,” LaCroix says. “Sometimes things that are ‘lost’ don’t stay lost, and when we find them, we have new evidence. But what’s interesting, and important, to remember is how much of it is chance.”