Near the heart of the main quads, the Swift Hall Cloister Garden sometimes provides a plein air classroom, sometimes a needed moment of Zen. (Photography by Anthony Arciero)

Two new courses illustrate how the Divinity School is broadening its scope to include more world religions.

The list of people who died in February begins in 1924.

Rev. Todd Tsuchiya of the Midwest Buddhist Temple slowly reads their names aloud. He’s accompanied by somber, beautiful piano music—an improvised version of “Nadame,” a gatha, or hymn, used at funerals and memorial services—played by jazz pianist Bob Sutter. At the sound of each name, family members and friends of the deceased line up to add a pinch of incense to the burner.

It’s the first Sunday of February, the temple’s monthly memorial service. Stephan Licha, assistant professor in the Divinity School and affiliated faculty with the Center for East Asian Studies, sits near the front of the room, surrounded by his students. The visit to the temple is the first of three field trips for his course The Globalization of Japanese Religions.

“Oshoko, or the offering of incense, represents the acceptance of transiency and fulfillment in life,” explains the “Buddhist etiquette” page on the temple’s website. For those new to Shin Buddhism, the page gives explicit instructions: Stop two steps back from the table and bow. Beginning with your left foot, step up to the table. With your right hand, take a pinch of incense and drop it in. Then put your hands in gassho—prayer position—and bow. As a visual example, there’s a photo of an elderly man, incense in his right hand, a cane in his left.

In class the previous week, Divinity School student Joe Troderman gave a presentation on Shin Buddhism, which was brought to the United States by Japanese immigrants: “lots of farmers looking for new opportunities” who settled in California. Founded by Shinran Shonin (1173–1263), Shin Buddhism—unlike many forms of Buddhism—rejects monasticism. Priests can be married. Families worship together.

As Reverend Tsuchiya reads down the list of Japanese names, there’s a noticeable change beginning with those who died in the mid-1950s: more and more American first names. Roy, Frank, Phyllis, Harry, Doris—names not common today but popular around World War II.

The story of the Midwest Buddhist Temple—which began in 1944 as the Midwest Buddhist Church—is inseparable from the history of World War II and Japanese internment. The Japanese community in Chicago dates from this era, when former detainees resettled here.

Under pressure to assimilate to American culture, Japanese Buddhists adopted a number of religious practices from Christianity: Sunday morning worship. Pews rather than floor cushions or mats. A service—songs, readings, and a dharma talk (akin to a sermon) about halfway through—that borrows from Christian practices. There’s also chanting in Japanese, but with each generation, fewer and fewer members of the community speak the language.

After the service, the UChicago group joins the community for an assemble-your-own soup bar in the temple’s basement. (You can choose chicken, tofu, Spam, vegetables, pickled vegetables, noodles or rice, and miso or chicken broth.)

Chatting over soup, the temple’s recently retired minister, Rev. Ron Miyamura, speaks ruefully of his own struggle with Japanese. When he went to Japan in 1970 for three years of religious training, he thought it would be easy to pick up the language, because he was “young and dumb,” he says. By the third year, “I kind of understood.” The younger generation, Licha explains later, can do all of their religious training and even their ordination in the United States.

“While the temple has roots in Japanese-American culture,” the history page of its website states, “MBT enjoys a growing diversity.” Just one example: a member named Cynthia who grew curious about Buddhism after reading Hermann Hesse’s novel Siddhartha in the 1970s.

When Licha was growing up in Innsbruck, Austria, he had a public school religion teacher—a lapsed Jesuit—who got him interested in Buddhism. So did the early 1970s TV show Kung Fu (which he watched dubbed in German), starring David Carradine as a Buddhist monk. At 18, Licha was ordained a Buddhist priest.

By his late 20s, he had suffered “in Christian terms, what you could call a crisis of faith,” he says. He turned instead to the academic study of Buddhism, earning a PhD at the University of London’s SOAS in 2012, followed by postdoctoral work at Waseda University and the University of Tokyo.

Licha came to UChicago in 2023. His course The Globalization of Japanese Religions—the Divinity School’s first-ever on this topic—covers Buddhism, Christianity, Shinto, and more.

On the Tuesday after the temple field trip, the readings include “The Beginning of Heaven and Earth.” The story seems unfamiliar at first … then uncannily familiar and unfamiliar at the same time.

In the beginning Deusu was worshiped as Lord of Heaven and Earth … Deusu has two hundred ranks and forty-two forms, and divided the light that was originally one, and made the Sun Heaven, and twelve other heavens. … Deusu then created the sun, the moon, and the stars, and called into being tens of thousands of anjo just by thinking of them. …

One day while Maruya was reading a book, words appeared mysteriously on the page to announce that the Lord was presently to descend from heaven. … Kneeling before the Biruzen Santa Maruya, the anjo said, “The Lord of Heaven is due to descend to earth, so please let us use your young and fresh body for the purpose.”

It’s one of the few texts from the Kakure Kirishitan tradition in Japan, “an indigenous form of Christianity,” as Licha calls it.

Christianity first came to Japan “by accident,” he tells the class, when a Portuguese trading ship on the way to China wrecked off the coast in 1543. Jesuit missionaries arrived soon afterward, and at first were welcomed: “The Japanese thought the Jesuits were just a really weird kind of Buddhists.”

The confusion originated partly from a translation mistake. It took some trial and error to find the best Japanese word for “God” in the Christian sense. The Jesuits “were using all kinds of different terms, including ‘Dainichi,’ which is actually the name of a Buddha,” Licha says. Eventually they settled on a version of the Latin word “deus.”

In the 17th century, the missionaries were expelled, and Christians persecuted. During this period, when Christianity was practiced in secret and orally transmitted, the beliefs of the Kakure Kirishitan, or Hidden Christians, took form.

By the mid-1800s, when Christianity was no longer outlawed, missionaries returned. Some of the underground Christians returned to the Catholic Church. But some clung to their unorthodox beliefs, for which they had suffered such persecution.

Small numbers of Kakure Kirishitan survive in Japan today, and “their traditions are still very much surrounded by secrecy,” Licha says. He shares an anecdote: Someone he knew in graduate school spent months gaining the trust of a Kakure Kirishitan community. One day an elderly man leaned over and whispered a “secret” prayer in her ear: the very famous, not at all secret, Kyrie Eleison (Lord, have mercy).

The second wave of Christian missionaries included not just Catholics, but also Protestants from all different denominations. In response to the contradictory teachings, some Japanese formed their own indigenous Christian groups: the Nonchurch Movement, Christ Heart Church, Living Christ One Ear of Wheat Church.

It’s like “the mirror image” of Buddhism in the United States, Licha says. A student at the front nods. Licha’s take: in Japan, Christianity has been transformed into a Japanese religion—just as in America, Buddhism has become an American one.

American Buddhists and Japanese Christians face “a similar problem,” Licha explains in a later interview: “A nonmatching religious identity.” As a result, “just as the Buddhists in America start to evolve new forms of Buddhism, so the Christians in Japan start to evolve new forms of Christianity.”

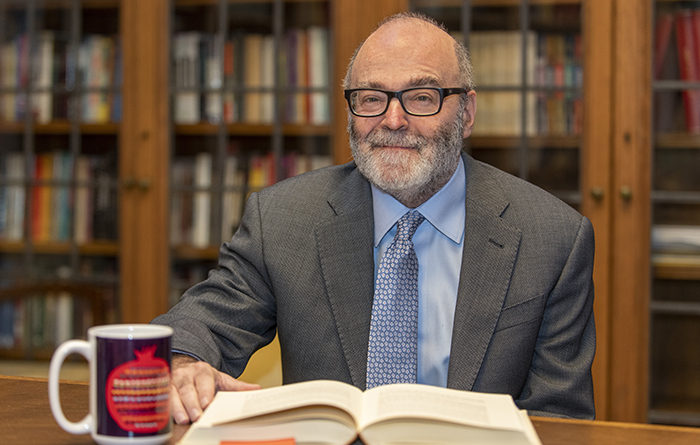

When John D. Rockefeller gave the original endowment of $1 million to found the University, he earmarked $200,000 ($6.8 million in 2024) for the Divinity School, says James Robinson, the Nathan Cummings Professor of Jewish Studies, who has served as dean since 2021. “Not a seminary but a divinity school,” he says, “focused on the critical study of religion.”

The Div School may be one of the oldest constituent parts of the University—and will mark the centenary of Swift Hall in 2026—but it’s nonetheless widely misunderstood. At meetings with University members whom he is too diplomatic to name, Robinson has been asked if he would like to open with a prayer. Over the years, he has developed stock answers to the questions and quips he hears again and again.

Q. “Are there atheists at the Divinity School?”

A. “That might be a requirement to begin the academic study of religion.”

Q. “What do you do over there—do you divine?”

A. “We live near a lake. So it’s really not that hard to find water.”

To be fair, the Div School is complicated. True, it offers coursework in the critical study of religion for students at all levels, undergraduate through PhD. At the doctoral level, students can choose among 11 tracks, including anthropology and sociology of religions, history of Christianity, history of Judaism, Islamic studies, and religions in the Americas. The critical study of religion is an inherently interdisciplinary field, encompassing history, art history, literary criticism, anthropology, and more. The Divinity School’s faculty, who often have joint appointments in other departments, reflect that.

But there is also a master of divinity program focused on practical training, which includes such courses as Arts of Religious Leadership and Practice: Spiritual Care and Counseling (read more about this course). The Div School does not ordain; MDiv alumni who want to become ministers must pursue that elsewhere. The MDiv is not just for aspiring ministers or chaplains, either. One student, who has a background in community organizing, considers Marxism to be his tradition.

Rockefeller was a devout Baptist, as was UChicago’s first president, William Rainey Harper, a scholar of Hebrew. The school itself was never Baptist; “it just was a divinity school,” says Robinson, “and divinity schools were Protestant.”

That began to change under Jerald Brauer, PhD’48, who served as dean from 1955 to 1970. Brauer hired Mircea Eliade, a preeminent historian of religions as well as an author of novels and short stories. He also hired Jonathan Z. Smith, “who became one of the most famous figures at the University,” Robinson says. “He took history of religions to a different level.” History of religions, which pre-dates Brauer, “was created as sort of a clearinghouse for everything that wasn’t Christianity.”

The trend continued under subsequent deans. Hindu scholar Wendy Doniger joined the faculty in 1978. Three scholars in Jewish studies followed, starting in the 1990s: Michael Fishbane (1991), Joel Kraemer (1993), and Paul Mendes-Flohr (2000). Robinson himself, a historian of Judaism and Islam, was hired in 2003 when Kraemer retired.

As of 2000, doctoral students could focus on Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, “the nature of religion itself as a category,” Robinson says, “and then, of course, a full range of things related to Christianity—Christian art, history of Christianity, ethics, theology, philosophy.” Scholars of Christianity remain the largest segment of the faculty: 19 out of 33. But that 19 includes faculty with interests in less-studied areas. Angie Heo, for example, works on Coptic Christianity in Egypt. Karin Krause, a scholar in Byzantine studies, focuses on material culture.

The wood-paneled dean’s office, “for what it’s worth,” says Robinson, “used to be very gray and brown.” Now it’s layered with colorful artwork chosen “to reflect the complicated nature of the school.” There’s a statue of Ganesha. A Hebrew amulet. An image of the cat-headed Egyptian goddess Bastet. A massive crucifix—a replica of a processional cross from the 14th century—discovered languishing in a third-floor closet at Swift Hall: “Isn’t it beautiful?”

The course that Karin Krause is teaching during Winter Quarter, Africa’s Byzantine Heritage, includes a field trip too. But this field trip is turned up to eleven: a mandatory, fully funded weekend visit to New York City. She’s taking her students to see the groundbreaking exhibition Africa & Byzantium at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

“Art history has long emphasized the glories of the Byzantine Empire (circa 330–1453),” reads the Met’s description of the show. “Less known are the profound artistic contributions of North Africa, Egypt, Nubia, Ethiopia, and other powerful African kingdoms whose pivotal interactions with Byzantium had a lasting impact on the Mediterranean world.”

When Krause, associate professor of Byzantine art and religious culture, heard about Africa & Byzantium a year ago, she applied for, and won, a Curricular Innovation and Undergraduate Research grant from the College. Because of that, only undergrads could enroll.

It’s the seventh week of Winter Quarter—the last week before the much-anticipated trip—and Krause is showing her students a slide of three coins they will see at the Met. The coins come from Aksum, capital city of the Kingdom of Aksum, which overlaps present-day Eritrea, northern Ethiopia, southern Yemen, eastern Sudan, and much of Djibouti.

It’s the earliest known example of a cross used on coinage—“much earlier than in the Byzantine Empire further north,” Krause points out. The Aksumite Kingdom was one of the first Christian nations, she explains; its leader converted in the fourth century. The coins feature Greek lettering, though Greek was not commonly spoken, indicating that the Aksumite Kingdom “looked for inspiration in Byzantine coins.”

Interesting as they are, the coins are not the most astonishing artifacts discussed in Krause’s lecture today. That distinction goes to the Garima Gospels, two illuminated manuscripts from the Monastery of Abuna Garima in Ethiopia. Dating to the sixth century, the books contain some of the earliest known portraits of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, authors of the four canonical gospel accounts of the life of Jesus.

The Garima Gospels were “discovered” by an English artist, Beatrice Playne, in 1948. Women are not allowed in the monastery, but the obliging monks brought the volumes outside for Playne to view. Jules Leroy, a renowned French scholar, published the first article on them in 1960.

Sadly (or happily, depending on your viewpoint), the students will not see the Garima Gospels in New York, because the books have never left the monastery. In 2006 the Ethiopian Heritage Fund sent an English bookbinder to Ethiopia to painstakingly repair them. The gospels, which are still in use by the monks, are now housed in a small museum on the monastery grounds.

The text is written in Geez, which is no longer spoken but is used as a liturgical language—parallel to Coptic, which was covered the week before. “I really like the writing. It’s very beautiful,” Krause says. “Very graphic.” Geez is a Semitic language like Hebrew and Arabic, she points out, but unlike most Semitic languages, it’s written left to right.

Because the language is less commonly taught, the Garima Gospels are understudied. It wouldn’t be that hard to learn “at least the basics,” Krause says, if anyone in the class “would like to join that small group of scholars who are experts in Ethiopian manuscripts.”

She ends the class with an exhortation to her students: “At this university, for instance, there seems to be a certain canon of texts that are studied over and over again,” she says. Instead, students should consider giving “more attention” to texts that are “more remote.”

After seven weeks of intensive study and preparation, the field trip is finally here.

On Friday at 8 a.m., Krause, course assistant Kate Goza, AM’22, and their students depart for New York City. The schedule for the weekend: four hours in the museum on Friday, followed by an Ethiopian dinner. Eight hours in the museum on Saturday (“with two or three breaks,” Krause says, since they will be standing the entire time). Then another four hours on Sunday.

The exhibition space, they discover, is dark, with wallpaper chosen to “evoke a temple setting” (as a student describes it in his reflection paper), with “subtle, golden accent walls and two-dimensional evocations of columns.” The space conveys “the same sacredness as the original artists sought to imbue into the work.”

The atmosphere is “distinctly church-like,” another student agrees. She notices this especially “when others would raise their voices, which, to me, felt wrong in the space.”

Each student takes a turn delivering a talk—topics include mosaics, icons, manuscripts, spiritual objects, and more—similar to their oral presentations earlier in the quarter. Krause studies material culture, and her course attracted art history majors as well as religious studies majors. But there are also students who had no art history background. Others came in knowing nothing about Christianity.

Giving a talk in a crowded museum, the students quickly discover, is not as simple as in Swift Hall. Those who picked mosaics, displayed on the walls, have an easier time. The students whose artifacts are in the center of the room tend to create a logjam. They also draw eavesdroppers. One museumgoer could not resist participating: “While I cannot fault him for being interested,” the student presenter wrote in their response paper, “he was a little distracting.”

Seeing the artifacts in person is a revelation. The Ethiopian healing scrolls were intended to be worn, and that’s evident from their condition. Manuscripts have signs of wear and notes in the margins. Heartbreakingly, some artifacts show evidence, as one student observes, of “poor conservation practices and destructive treatment.”

Another student is surprised by a bridal chest from Nubia: its large size, its lock (“I was struck by its expert craftsmanship and beauty”), but also its damaged state. In person she could see how someone had “pried the chest open and destroyed much of the object.”

The group also discusses the ethics of what they’re looking at—and maybe should not be looking at. “Not much is known about healing scrolls because many owners did not want to give theirs away,” one student notes in their response paper. “Indeed, most people kept their scrolls on their person at all times. It is very unlikely that the owner of the scroll would approve of their healing scroll being presented at a museum.”

The schedule allows for two hours of free time before flying back to Chicago on Sunday: Krause wanted students to be able to explore the rest of the museum or see a bit of New York.

Sitting in the Met’s café, taking a break after an intense and exhausting weekend, Krause gets a text from a colleague who also studies Byzantine art.

She’s seeing the show herself, and has just encountered some of Krause’s students. (Why spend just 16 hours in an exhibition when they could spend 18?) She was so surprised to hear young people discussing the rare artifacts with such knowledge and authority, she could not resist asking them who they were.