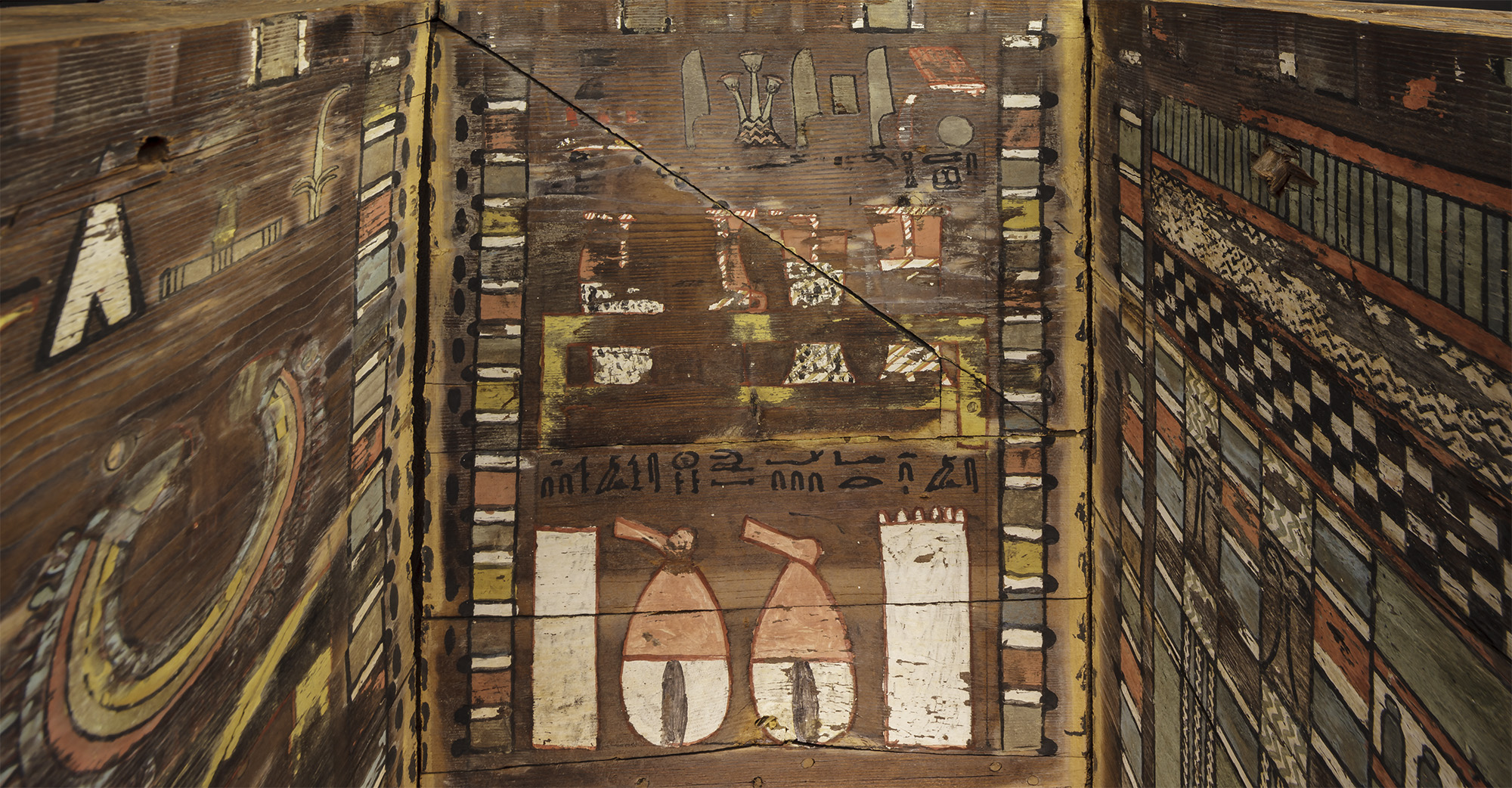

The interior of the coffin of Egyptian army commander and scribe Ipi-Ha-Ishetef is decorated with items the deceased would need in the afterlife, such as food, jewelry, and weapons.(All photos in this story courtesy the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures at the University of Chicago; coffin of Ipi-Ha-Ishetef; ISACM E12072AB; cedarwood, paint; Egypt, attributed to Saqqara, First Intermediate Period, Dynasty 9–10 [2165–2134 BCE])

An ISAC researcher and conservator illuminate the role of color in the ancient world.

Over the past two decades, exhibits like Gods in Color and Chroma have popularized the idea that the ancient world was awash in color. But what do we really know about how ancient peoples understood and used color in their art, architecture, and clothing? In Color in Ancient Art, an adult education class offered by the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures in February, continuing education manager Tasha Vorderstrasse, PhD’04, and senior conservator Alison Whyte shared their knowledge over three evenings on Zoom. The Magazine was there to capture the spectrum of their insights.

Did ancient people perceive color the same way we do today? Vorderstrasse posed this question in the first class. Her answer—perhaps surprising—was, in some fundamental ways, no. Since dyes and pigments came only from natural sources, the range of available colorants in the ancient world was limited. They also could be costly to produce and apply, so most people had limited access to colorful linens and decorations. Our current theory, in which color is seen as being on a spectrum, is also relatively recent, dating to Isaac Newton’s work with prisms in the mid-17th century. And synthetic dyes, which made a wider range of colors more readily available, date only to the 19th century. All these differences influence our perception.

Vorderstrasse, who specializes in the material culture of Central and West Asia, North Africa, and the South Caucasus, went on to discuss color in ancient languages. Scholars’ understanding of how ancient people in the Near East and North Africa described color, she said, has advanced in recent years, upending a previous belief that ancient cultures had few words for color—especially equivalents for abstract English terms such as “blue” and “green.”

Numerous studies over the past half century show that Egyptians in fact had a greatly varied vocabulary for color. But it was only in 2019 that Assyriologist Shiyanthi Thavapalan reassessed ancient Mesopotamian language and found that speakers of Akkadian also had many terms for color; however, they tended to describe them in relation to qualities like brightness and luster rather than hue.

Certain Akkadian color terms derived from precious materials like gold and lapis lazuli, Vorderstrasse added, are challenging to understand. A term like lapis lazuli (uqnûm) might be used to say that an object has the stone’s dark blue hue, or “how shiny it is, or how valuable it is.” She shared a puzzling description: “red-tinted lapis lazuli–colored glass.” The phrase may refer to a purple hue, to the veining that characterizes some lapis lazuli, or to some other quality. To add to the uncertainty, “red-tinged lapis lazuli” also appears in descriptions of dyed wool from Mesopotamia. Were such textiles multicolored or purple? Or was the semiprecious stone meant to invoke the expensive dye?

Vorderstrasse’s work on Coptic, a language spoken in Egypt in the first millennium CE, raises similar questions. Scholars disagree on the meaning of the word djēke or djō(ō)ke, translated variously as “purple” or as “embroidered” or “decorated.” The scarce and valuable Tyrian purple dye was derived from murex snail shells, each of which produced only a few drops of the discharge used for dye. Embroidery was a similarly laborious and costly process. “Is it because purple is so valuable that it starts to mean [embroidered]?” Vorderstrasse posited. Or “Is it that embroidery is expensive and it starts to also mean purple?” It’s a question without, as yet, an answer.

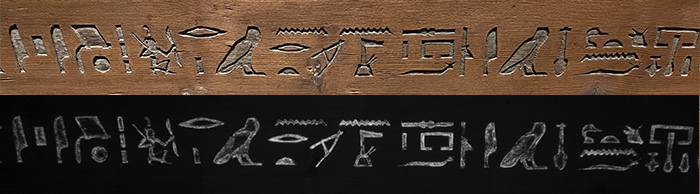

Moving from mind to matter, the final two classes covered physical evidence of how ancient people applied color to artwork and decoration. From unfinished Egyptian tomb paintings, Vorderstrasse said in the second class, we can learn a lot about how painters worked with great care: first blocking out figures in red, then layering pigments to create different color effects, and finally outlining details in black. Yet questions remain about how colors would have appeared hundreds of years ago and even how realistic color application was meant to be—and such questions can prove a challenge in the study and conservation of ancient objects.

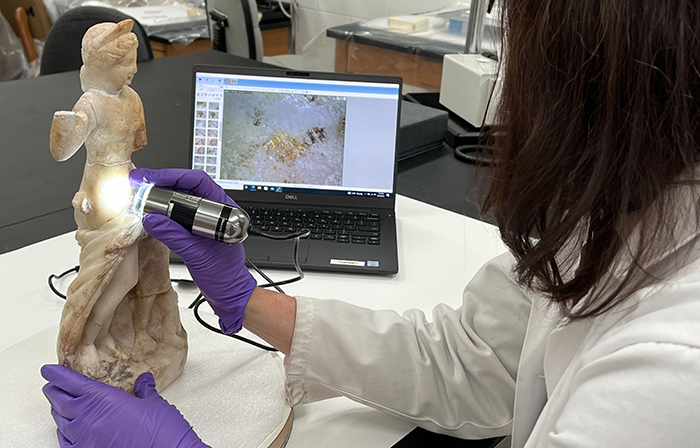

In the final class, senior conservator Alison Whyte used an arsenal of slides to show key strategies the ISAC conservation team uses when faced with an object that needs treatment. A number of different analytical techniques are at their disposal to determine how color was used, which helps them assess what interventions will be most effective to analyze and protect pigments on items in the museum’s collections.

Conservation only became a formal field of study in the 1950s, explained Whyte. Before that, museums hired artisans to restore the appearance of objects. Sculptor Donato Bastiani, seen at left, held such a role at ISAC from the 1930s to the 1950s. Today the ISAC conservation team is focused not on aesthetics but rather on protecting objects from environmental dangers like pests, light, and humidity, and ensuring this cultural heritage can be studied and enjoyed for years to come.

One of Whyte’s case studies was a marble statuette of Venus and Cupid. Originally from Lebanon, the piece dates to the second to third century CE. ISAC conservators could tell the statuette was decorated with red pigment—for example, on the cloth draped around Venus’s legs and on Cupid’s quiver. In 2022 they worked to analyze those pigments.

Examination of the statuette with a digital microscope showed the presence of gold, which in some places appeared to be layered over a dark-red pigment—a common practice, Whyte said, likely used to enhance the gold’s appearance. The gilding appeared to mark an X shape on Venus’s torso, suggesting this work may have been decorated similarly to a statuette of Venus discovered in 1954 in Pompeii and dubbed “Venus in a Bikini” by the Italian press for the extensive body jewelry painted on her nude figure.

Whyte then scanned the statuette with an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer. Originally designed to be used in geological applications and for quality control of modern metals, the instrument shoots X-rays at an object and reads the patterns atoms produce in response. Since each element produces a unique pattern, XRF can identify certain elements present on the object’s surface. Using XRF, conservators were able to confirm the statuette was decorated with gold without having to remove a sample—and that that the dark-red color contained a lot of mercury and sulfur. They theorized this pigment contained cinnabar, made from a mercury sulfide ore, a theory they were later able to confirm by testing a sample of the pigment.

Viewing the statuette under ultraviolet light—a test initially undertaken to see the extent of adhesives previously applied to the piece, which Whyte later carefully removed—allowed conservators to confirm that two different red pigments had been used on the statuette. In addition to the darker cinnabar-based pigment, a lighter, pinkish-red pigment fluoresced orange-red under UV light. Whyte believes this pigment likely contains madder root, a common colorant known to fluoresce in this way.

A second case study, the coffin of army commander and scribe Ipi-Ha-Ishetef, dates to about 2165–2134 BCE. The piece, from Saqqara, Egypt, underwent conservation treatment from 2014 to 2015 with support from an American Research Center in Egypt grant. The goal was to stabilize pigments that were flaking off the wood. To find the right consolidant (material to bind the pigments to the piece), conservators first analyzed the coffin and the pigments.

The interior of the coffin is decorated with items the deceased would need in the afterlife, like food, jewelry, and weapons. On one long side is a door through which the spirit could exit. The mummy would have been placed on its side, facing that door. On one of the short sides, a pair of painted sandals points toward the door, showing where the mummy’s feet would have rested.

The deterioration of the ancient paint, Whyte noted, reveals how paint was layered onto the coffin. On a necklace, for instance, the wear makes clear that painters enlarged the beads, which were initially outlined in red.

Conservators also learned that the coffin exterior had been decorated with Egyptian blue, the oldest known synthetic pigment. Made from calcium, copper, and silica, it was used, most scholars agree, as a cheaper imitation of lapis lazuli. Because Egyptian blue fluoresces in the infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum when exposed to visible light, conservators were able to confirm its presence here with a technique called visible-induced luminescence imaging, using a camera modified to record its characteristic luminescence.

Project conservator Simona Cristanetti tested many consolidants to find one that would stabilize the pigments without changing the appearance or finish of the piece. In 2015 the coffin was put on display in ISAC’s galleries for the first time in 20 years—where you can view it today.