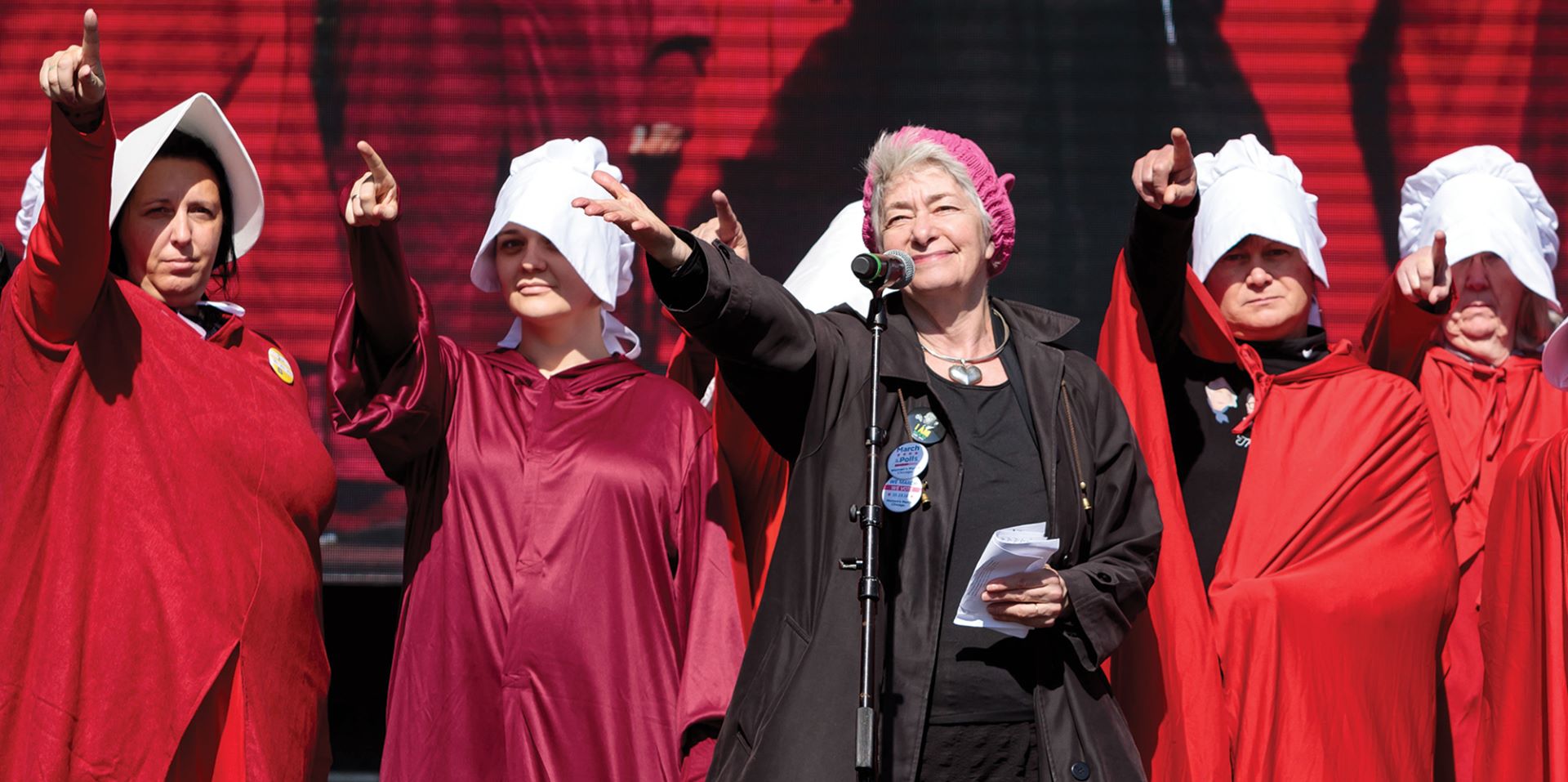

Heather Booth speaks at the Women’s March to the Polls in Chicago in early October 2018. (Photography by John Zich)

For activist Heather Booth, AB’67, AM’70, the personal has been the political for more than 50 years.

On a bitter October day, thousands of people have converged on Columbus Drive for the Women’s March to the Polls.

Among them is Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle, AB’69, MAT’77, threading her way toward the stage through the thick crowd. Preckwinkle campaign workers are circulating too, collecting signatures to get her on the 2019 Chicago mayoral ballot.

Artist Jacqueline Edelberg, AB’89, AM’91, PhD’96, in a Mylar dress and silver face paint, is collecting hope notes for children separated from their parents at the border. (Her project, “Mylar for Disco, not Deportation,” references the blankets issued to the kids.)

The marchers’ accessories include the usual Trump-in-a-diaper balloons, pussy hats in assorted shades of pink, and impassioned hand-lettered signs: some sincere, some furious, some obscene. One lone dissenter trolls the crowd with a sign reading (in part) “Trump Is Your President. Get Over It.” He elicits a few half-hearted boos.

Heather Booth, AB’67, AM’70, was scheduled to speak at 11 a.m. By the time she takes the stage closer to 12:15 p.m.—after numerous other speakers, singers, rappers, and video messages from prominent Democrats—the crowd has grown restless in the cold.

“Are you ready to resist?” Booth yells into the microphone. “Are you ready to organize?” Her fiery delivery, like a union boss or street preacher, is surprising from a diminutive woman in her 70s. She’s a sparrow with the roar of a lion. “Are you ready to fight? Are you ready to WIN?” The crowd yells back its assent.

“We are in a time of both great peril and inspiration,” Booth declares. “The inspiration is all around us—if—we—organize! It’s been true in history, it’s true now.”

In the summer of 1964, she says, she was part of the Freedom Summer Project in Mississippi, one of hundreds of northern college students who traveled south to help register voters and bring national attention to the civil rights movement. “Because people organized, within a year there was a Voting Rights Act,” she says. “When we organize, we can change the world.” The crowd claps and cheers.

Back at school, she learned that a friend was “pregnant and nearly suicidal.” At the time abortion was a felony in Illinois. Through connections in the civil rights movement, she helped her friend find a doctor. “And then word must have spread and someone else called,” she tells the crowd. Booth’s act of compassion for a friend grew into Jane, an underground abortion service that lasted until 1973, the year of the Roe v. Wade decision.

As she tells the story of Jane, 15 women dressed like handmaids from the dystopian television show The Handmaid’s Tale silently assemble behind her. They remain there, eyes downcast, for the rest of the speech. “We will never go back!” Booth insists.

She quotes historian Howard Zinn, noting that her son Gene teaches his work in the Chicago Public Schools: “‘It would be naive to depend on the Supreme Court to defend the rights of poor people, women, people of color, dissenters of all kinds. Those rights only come alive when citizens organize, protest, demonstrate, strike, boycott, rebel, and violate the law in order to uphold justice.’ When we organize, we—can—win—back—justice!”

Booth pulls out a pussy hat and puts it on dramatically. The crowd roars its approval.

“So are you ready to resist?” she hollers. “Are you ready to—” But the audience is cheering so loudly, it drowns her out.

A recent documentary, Heather Booth: Changing the World (Lilly Rivlin, 2016), describes Booth as “the most important person you’ve never heard of.” (The video, which aired on some PBS affiliates in December, may change that. There are also two Hollywood movies about Jane in production: This Is Jane, directed by Kimberly Peirce, AB’90, and Ask for Jane.)

Along similar lines, a 2017 Huffington Post article, “She’s the Best Answer to Donald Trump You Never Heard Of,” calls Booth “one of the nation’s most influential organizers for progressive causes. Inside almost every liberal drive over the past five decades—for fair pay, equal justice, abortion rights, workers’ rights, voter rights, civil rights, immigration rights, child care—you will find Booth.”

“A polite, soft-spoken woman who introduced herself as Heather Booth” is how conservative commentator Glenn Beck described her on his Fox News show. “She seems like a nice enough lady, but she’s actually very important, isn’t she?”

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact beginning of Booth’s career. Maybe it starts in 1973, with the founding of Midwest Academy, a training center for progressive organizers. Maybe in 1965, when she started Jane as a second-year living in New Dorms (later Woodward Court, now defunct). Maybe in 1964, during Freedom Summer.

Maybe 1963, when shortly after her arrival at UChicago she joined the Chicago Public Schools boycott to protest inferior facilities for African American students. Or earlier, when as a young teenager growing up in Long Island she passed out fliers against the death penalty in Times Square. “Someone spit on me,” she recalled in a 2012 interview. “It was pretty shocking.”

“If you look at significant times in the movement, Heather is there someplace,” her friend Jane Silver says in Heather Booth: Changing the World. “I mean, it’s like Zelig.” The two spent the summer of 1963 working on a kibbutz in Israel—another possible starting point for her origin story.

“I don’t know that I had a concept of a career,” Booth says in a profile for Women’s Information Network (WIN), a resource for young pro-choice Democratic women; Booth serves on its advisory council. “I had a sense of values and purpose and wanted to have an impact in building a better society.”

And yet Booth’s career is remarkably coherent: no switchbacks, no meanderings, just a strong straight line in a leftward direction. After years of organizing, she shifted into electoral work in 1980: “otherwise we are fighting with one hand tied behind our back.” She was deputy field director for the 1983 campaign to elect Harold Washington, the first African American mayor of Chicago. She was field director for the 1992 campaign for Carol Moseley Braun, JD’72, the first black woman to serve in the US Senate.

In 2000 she was director of the NAACP National Voter Fund, which helped to increase African American election turnout by nearly two million voters. In 2010 she was the founding director of Americans for Financial Reform, which helped create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (In the documentary, Senator Elizabeth Warren says that when she wanted to establish the bureau and had no idea how, she was given two words of advice: “Heather Booth.”)

That’s just a whistle-stop tour of Booth’s career.

Heather Booth, née Tobis, is a Southerner, sort of. She was born in 1945 in Brookhaven, Mississippi, where her father, a physician in the Army, was stationed, but spent most of her childhood in Brooklyn and Long Island. Decades in Chicago and Washington, DC, have not entirely erased her New York accent, even on frequently used words like “call” (i.e., “cawl”).

It’s a few hours before her speech at the Women’s March; Booth has taken some time to chat in the press tent, just behind the stage where bands are doing ear-splitting soundchecks. She wears her pink hat and a thin brown coat more suitable for the climate of DC, where she has lived since 1989. But Booth—who has spoken often of how boring, uncomfortable, and difficult organizing can be—is too tough to complain.

Instead she talks about how happy she was as an undergrad: “I felt my world opened up,” she says. “I found people of shared values, shared commitments. It was challenging, creative, engaging. I loved being at the University from the minute I arrived.”

Her most memorable professors include the late historian Jesse Lemisch, “who helped to explain how history is made from the bottom up,” she says, not merely “the history of great men.” From sociology professor Dick Flacks (who had cofounded Students for a Democratic Society a few years before) she learned that “if issues are social problems, they can have social solutions,” she says. “You can take social action to address those problems.”

Though she loved her classes, Booth chafed against some University policies, such as the 11 p.m. curfew for women in campus housing. (The men’s curfew was midnight.) One night she came in late because she was comforting a friend after a breakup. She was interrogated and searched for contraceptives. “It was a much more innocent time,” she says, “and I was outraged that they would think I had contraceptives.” After a sleep-in at the flagpole on the quads and other protests, the so-called parietal hours became one of those abandoned practices that to younger generations hardly sound real.

When another friend, who lived off campus, was raped at knifepoint, Booth went with her to Student Health to get a gynecological exam. (It’s a story she repeats during her speech, not specifying which university.) Her friend was told gynecological exams weren’t covered. “She was also given a lecture on her promiscuity,” Booth says. (Here, during the speech, the audience boos with outrage.) “But over time, because people organized and protested—not just at the university, but in the country—of course Student Health now covers gynecological exams. But unless you organize, you can’t take any rights for granted.”

The sexism women experienced within the student movement was another irritant. In 1965 Flacks encouraged her to attend a Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) conference in Champaign-Urbana to discuss what was called, incredibly, “The Woman Question.”

“Women would be talking and the men would be doing what we now call mansplaining,” Booth says. “The women would say, ‘I’m not listened to,’ and the men would say, ‘Oh yes you are.’ ‘You’re just expecting me to make the coffee.’ ‘Oh no, that’s not true.’”

Soon afterward, at a campus SDS meeting in Ida Noyes, Booth was addressing the group when a man interrupted her: “Ah, shut up.”

“I was so shocked that he would be so rude that I tapped all the women on the shoulder after I was done speaking, and I said, Let’s go upstairs,” she says. Together they formed the Women’s Radical Action Project (WRAP), one of the first women’s liberation groups in the country. (Booth won’t name the man whose boorishness inspired it. “He’s since died,” she says. “He turned to me for advice and support in the later years of his life, and I never did raise this to him.”)

In May 1966, when Booth was a third-year, she was one of 450 students who participated in a sit-in of the Administration Building (now Levi Hall)—the beginning of a wave of nationwide student protests against the war in Vietnam. The University had agreed to provide the class rank of all male students to the Selective Service; lower-ranked students might lose their student deferments and be drafted.

The campaign, organized by Students Against the Rank, was eventually successful: the University stopped compiling an all-male student rank. But for Booth, the long-term significance of the sit-in was not political, but personal.

Paul Booth, a Swarthmore alumnus who was national secretary of SDS—its top job—came to support the protesters; at the time SDS’s national headquarters was on 63rd Street in Woodlawn. In the documentary he tells the story of their meeting “in a very sweet way,” Heather Booth says. The scene in the video unfolds like this:

“I spy Heather Tobis. This is what you say when you go to a sit-in if you want to meet somebody. You say, ‘Could I sit here?’ (He turns from the camera to Heather, smiles broadly, and directs the rest of the story at her.) And she said, ‘Yes!’ And then it became a sit-in. It lasted several days and nights, and we got to know each other very well.”

“We sat and talked, day and night, and after three days he asked me to marry him,” Booth says. “And after five days I said I would, but we should wait for a year, till I graduate.” (At the time, dropping out of college to get an MRS degree was not unusual.) “We were married until he died in January,” meaning January 2018.

Soon after they met, Paul Booth was pushed out of SDS for being a member of the “old guard”—at age 23. But like his wife, he went on to have a prominent career as an organizer; they made a formidable team.

Paul Booth was one of the first former campus activists to join the labor movement, retiring after 43 years with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees. He tried to build coalitions between the labor movement and progressive causes such as civil rights, immigrant rights, women’s rights, and peace. “It was a very grounded career,” he says in Heather Booth: Changing the World. “Just the opposite of hers.”

Almost immediately after their marriage in 1967, the Booths had to make a tough decision. “My husband was going to be drafted, and there was going to be a punitive draft because he was an antiwar leader,” Heather Booth recalled in an interview with the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union History Project. “One way to get out of the draft was to have a kid.” Their first son, Eugene, named for socialist labor leader Eugene Debs, was born in 1968. Their second son, Daniel, after Daniel De Leon, the socialist editor, was born in 1969.

In a 2017 speech for TEDx Pennsylvania Avenue, Booth describes those years: “In 1971 I was a housewife in Chicago with two little kids under three.” (“Housewife” is modest; she was also a leader of Chicago’s women’s liberation movement and coauthor of the 1968 feminist manifesto “Toward a Radical Movement.”) Booth and a group of other mothers founded the Action Committee for Decent Childcare (ACDC), holding community meetings to build support across the city. “People flocked to us,” Booth says in the TEDx Talk, “because they had been dealing with a problem that they felt was theirs alone, and just a personal problem, when in fact it was a social problem and needed a social solution.”

With no childcare, the kids came too: both Gene and Dan were marching before they could walk. (Gene was too young to remember the childcare demonstrations, but one of his earliest memories is sitting on his father’s shoulders, chanting in support of farm workers: “You got to boycott lettuce, you got to boycott grapes, you got to boycott the wine that Gallo makes, you got to organize, you got to unionize!”) Less than a year after its founding, ACDC won a simplified licensing process for childcare facilities and $1 million in city funding.

In 1973 Booth scored another win, a $5,000 back pay settlement; a few years earlier she had been fired from an editorial job for trying to organize the secretaries. With the money, and her husband’s help, she set up Midwest Academy, a training center for progressive organizers. Its first space was the basement of a church near Clark and Fullerton; it’s now on Kedzie just south of Lawrence.

Booth created the center “because it seemed the movement was falling apart,” she told the Chicago Reader in 1989. “My husband and I had left SDS in 1967, when it started to lose faith in the American public. We were called the ‘old new left.’ We had kids; we believed in the nuclear family; we didn’t do drugs. We believed there were a lot of positive lessons to learn from the ’60s, but better strategic planning was needed.”

In her TEDx Talk, she lists Midwest Academy’s three organizing principles:

- Based on values, win real improvements in people’s lives.

- Give people a sense of their own power to achieve those goals.

- Build for systemic structural change.

(Like anything political online, Booth’s TEDx Talk inspires polarized comments. On the one side: “She’s truly the only light in these dark times.” On the other: “Her talking style is very subtly egoic and manipulative. Her ultimate goal is not for democracy.”)

Midwest Academy is known for its detailed strategy chart, which includes numerous questions to help activists sharpen their focus: What constitutes victory? What short-term or partial victories can you win as steps toward your long-term goal? Who cares about this issue enough to join in or help the organization? Who are your opponents? What will your victory cost them? What will they do/spend to oppose you? How strong are they?

Both Heather and Paul had gone through the training program run by Saul Alinsky, PhB’30, often called the father of community organizing. Women couldn’t be organizers, Heather was told during the training. “It was a very male crowd,” Paul Booth recalls in Heather Booth: Changing the World. “It was a lot of testosterone. When Heather went to school, it was almost all fellas in the room.”

As a response, Midwest Academy’s first class was all women. Over 45 years, more than 25,000 activists from Planned Parenthood, NARAL, NAACP, the Sierra Club, and innumerable smaller groups have trained at Midwest Academy.

Heather and Paul Booth were married for more than 50 years. In 2004 Paul was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. But he showed no symptoms until a 2017 trip to Cuba with Heather and other friends. His death this past January was swift and unexpected.

Sitting in the press tent at the Women’s March, Heather Booth looks down at her hands in her lap. “It’s really thrown my world upside down,” she says quietly. “It’s quite stunning, what grief is, in a way that I didn’t understand it ever before. He was my partner. Not only the love of my life—everything.”

On the last day of his life, Heather had signed up for a sit-in on Capitol Hill, organized by Jews for Dreamers: “Civil disobedience in support of a pathway to citizenship,” she says. “I said I’d cancel it, of course. Paul said no, no, I really should go.”

Heather was arrested. When she returned to the hospital, “he was almost giddily happy,” she says. “He was looking at the live streaming pictures from the sit-in. Even on this last day of his life, he was committed to change. He kept up that commitment, and I try to carry on his commitment now.”

In the documentary video, there’s a shot of her making calls in her home office. Booth’s desk is a controlled chaos of papers and files, horizontal and vertical; pinned to a shelf is the phrase “Pessimism of the intellect and optimism of will.” It’s a quotation from Italian activist Antonio Gramsci, jailed by the Fascists in World War II.

“You don’t stop struggling because of a few setbacks,” Booth told the Chicago Reader in 1989, just before her move to DC. “Whenever I’m teaching an organizing class, I ask: ‘How are rights won? Are they given to us by some benevolent president or mayor? Or did they emerge from the struggles of people?’ If we don’t learn that change comes from struggle, we’re lost.”

In interviews and speeches, she returns relentlessly to one simple message: “If we organize, we can change the world.” It’s the title of her TEDx Talk about childcare and Midwest Academy. It’s in her interview with WIN—a network dedicated to building the next generation of Heather Booths—in all capitals.

The exact phrasing shifts. “If we organize…” is sometimes “When we organize…” or “Unless we organize…” Sometimes it’s followed by more specific advice about stamina, as in the WIN interview: “Realize we are organizing for the long haul—this is a marathon, not just a sprint,” Booth says. “So take care of yourself and each other.”

Updated 03.29.2019 to provide the appropriate credit for the photograph of Booth on a 1964 picket line in Shaw, Mississippi. The photograph was taken by Wallace I. Roberts and permission to use it was provided by the Roberts Family.