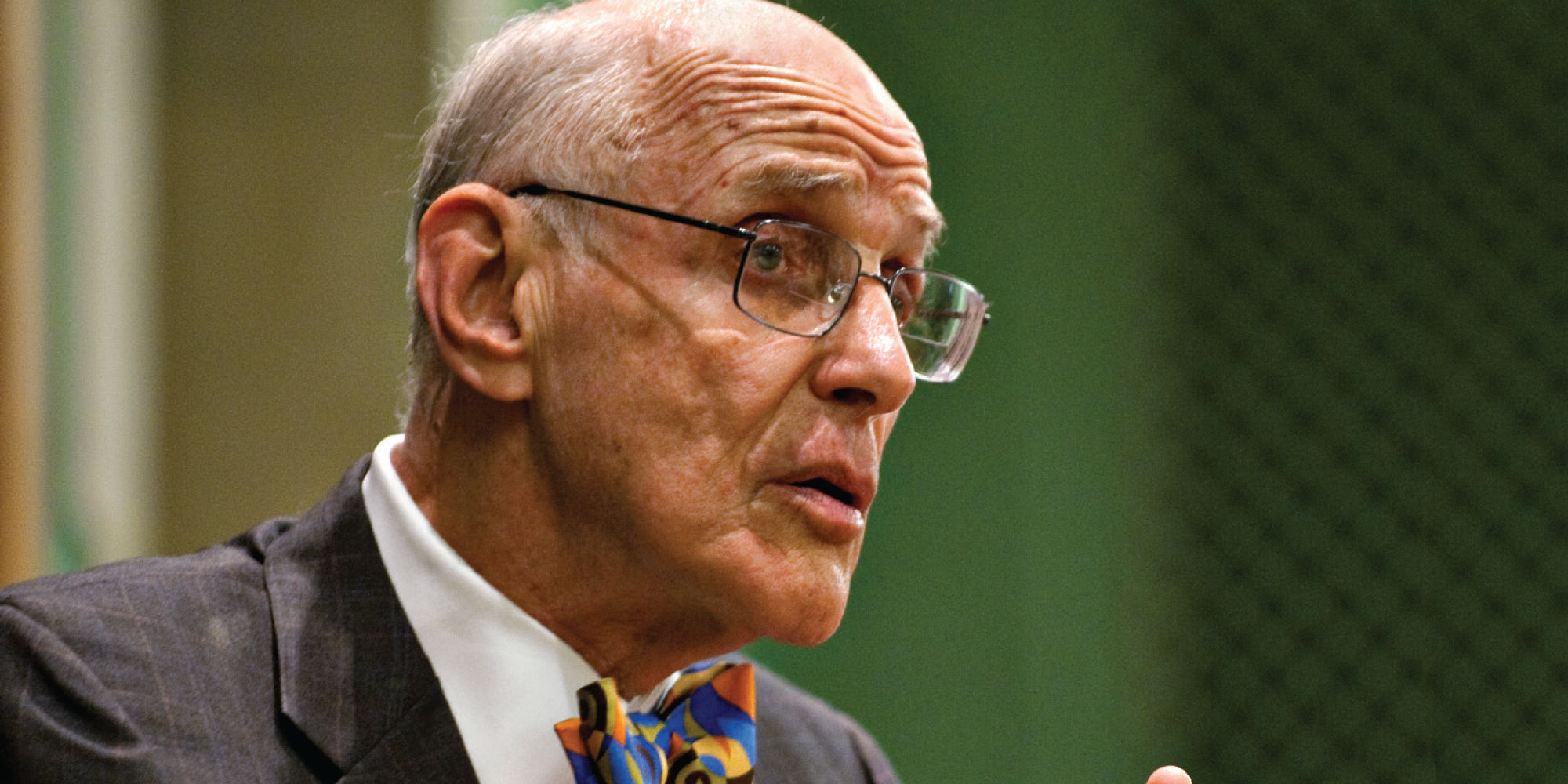

(Photo courtesy University of Michigan Law School)

Joseph Sax, JD’59 (1936–2014), helped establish the courts as a front line for environmental activism.

Picture Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1970, at the height of campus activism. On March 11, students, politicians, and activists including Ralph Nader gathered on the University of Michigan campus for a four-day teach-in on the environment. Singer Gordon Lightfoot and the Chicago cast of Hair performed. Among the other events was a mock trial with a 1959 Ford sedan as the defendant. The event was considered a dry run for the first Earth Day a month later.

That year Ann Arbor was also the site of a less theatrical but equally significant moment for the environmental movement: the publication of a scholarly treatise in the Michigan Law Review by Joseph Sax, JD’59.

In “The Public Trust Doctrine in Natural Resources Law: Effective Judicial Intervention,” the University of Michigan law professor posited that many natural resources, like shorelines, oceans, air, and some land, are held in public trust by the government for the benefit of present and future citizens.

Public trust can be traced back to Roman laws stipulating common ownership of shorelines and navigable waterways. The concept later made its way into English law, including the Magna Carta, which placed ownership of such resources in the hands of the monarch, who was to act as their trustee on behalf of the public.

Sax applied the principle broadly to natural resources—thus laying the groundwork for decades of legal action to protect the environment. His article has stacked up citations in court decisions and scholarly journals alike. To call it influential “is a gross understatement,” wrote University of California, Davis, law professor Richard M. Frank in the UC Davis Law Review. The article “had a catalytic effect among courts and environmental policymakers throughout the country,” establishing a legal rationale for suing organizations, individuals, or government agencies whose actions threatened natural resources. Sax became known as the father of environmental law by empowering others to defend those resources as a public trust.

Holly Doremus is one of many environmental lawyers and legal scholars Sax mentored. In a posthumous tribute in the Vermont Law Review, the University of California, Berkeley, law professor called her teacher’s work “directly responsible for both the development of the field” of environmental law “and the fact that within a decade or two the words ‘environmental law’ could be said out loud without embarrassment or apology at even the snobbiest of law schools.”

When Sax graduated from the University of Chicago Law School, environmental law wasn’t a field at all. Editor of the Law Review, he went on to work briefly as a labor lawyer for the US Justice Department and in private practice before joining the University of Colorado law school in 1962. There, the lifelong outdoorsman was assigned to teach water law. At the time, that field was focused on the rights to use resources rather than on the desire to protect resources—but Sax’s approach pivoted on the intersection of private and public interests. “The ideas that teaching water law triggered for Professor Sax,” wrote Doremus, “rapidly matured into a much broader vision of the nature of property generally.”

While at Colorado Sax helped the Sierra Club limit development on the Colorado River and designed his first course on conservation and the law.

When he moved to the University of Michigan in 1966, it was in part to collaborate with faculty from its School of Natural Resources (now the School for Environment and Sustainability). “Professor Sax,” noted Doremus, “was interdisciplinary before anyone was using that word.”

Of Sax’s many publications on the environment and the public good, “The Public Trust Doctrine” still stands out, its influence alive and well. Supporting his argument with case law, he examined public trust applications in several states. Most pivotal was the 1892 case Illinois Central Railroad Company v. Illinois.

In 1869 the state had passed an act granting the railroad title to more than a thousand acres of submerged Chicago lakefront stretching east of Michigan Avenue and a mile into Lake Michigan. The land represented almost all of Chicago’s commercial waterfront. Illinois had a change of heart, and after a protracted legal battle, the Supreme Court ruled in its favor in 1892. “When a state holds a resource which is available for the free use of the general public,” Sax wrote of the case, “a court will look with considerable skepticism upon any governmental conduct which is calculated either to reallocate that resource to more restricted uses or to subject public uses to the self-interest of private parties.”

Today the public trust doctrine has been applied in hundreds of federal and state decisions and adopted in 10 countries outside the United States. To share his ideas with a wider audience, Sax wrote Defending the Environment: A Strategy for Citizen Action (Knopf, 1971). His subsequent general audience books reflected on the nature of public goods—Mountains without Handrails: Reflections on the National Parks (University of Michigan Press, 1980) and Playing Darts with a Rembrandt: Public and Private Rights in Cultural Treasures (University of Michigan Press, 1999).

Neither the ideas in “The Public Trust Doctrine” nor a legal scholar calling for citizen action seem all that radical in 2020. But in his time, Sax’s activism “was viewed somewhere between disdain and alarm by most of his colleagues,” says Roger Conner, a former student of Sax’s at Michigan. “Professors weren’t supposed to do that. They would sully themselves with action. It would ruin their clarity of thought.”

Sax hardly confined his work to the academy. In 1969 environmental activist Joan Wolfe approached him to write what became the Michigan Environmental Protection Act (MEPA) of 1970. Based on the legal framework outlined in “The Public Trust Doctrine,” MEPA gave citizens, agencies, and other legal entities the right to sue over damage to resources held in the public trust. Sometimes called the Sax Act, it was considered especially robust for environmental protection legislation and served as a model for laws later passed in other states.

In 1986 Sax moved to UC Berkeley, closer to his three daughters, who all lived in California. Building on ideas that he’d first put forth in Mountains without Handrails, he wrote a paper on the proposed management of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park in Alaska. When Sax died 28 years later, the paper was still being used by the park’s superintendents, handed down from one to the next. His work on parks stewardship led to an advisory post with US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt during the Clinton administration.

In 2007 Sax received the Blue Planet Prize, often called the “Environmental Nobel.” He was gratified, Sax said, for the recognition of “the role that the rule of law plays in implementation of scientific achievement in the governance of our societies, and in assuring justice to those who have suffered environmental harm.”

Sax’s influence continues today through his honors and writings, as well as through the ripple effect of his teaching. Many of the law students he mentored became scholars, activists, and educators in turn—just another way he set precedent.