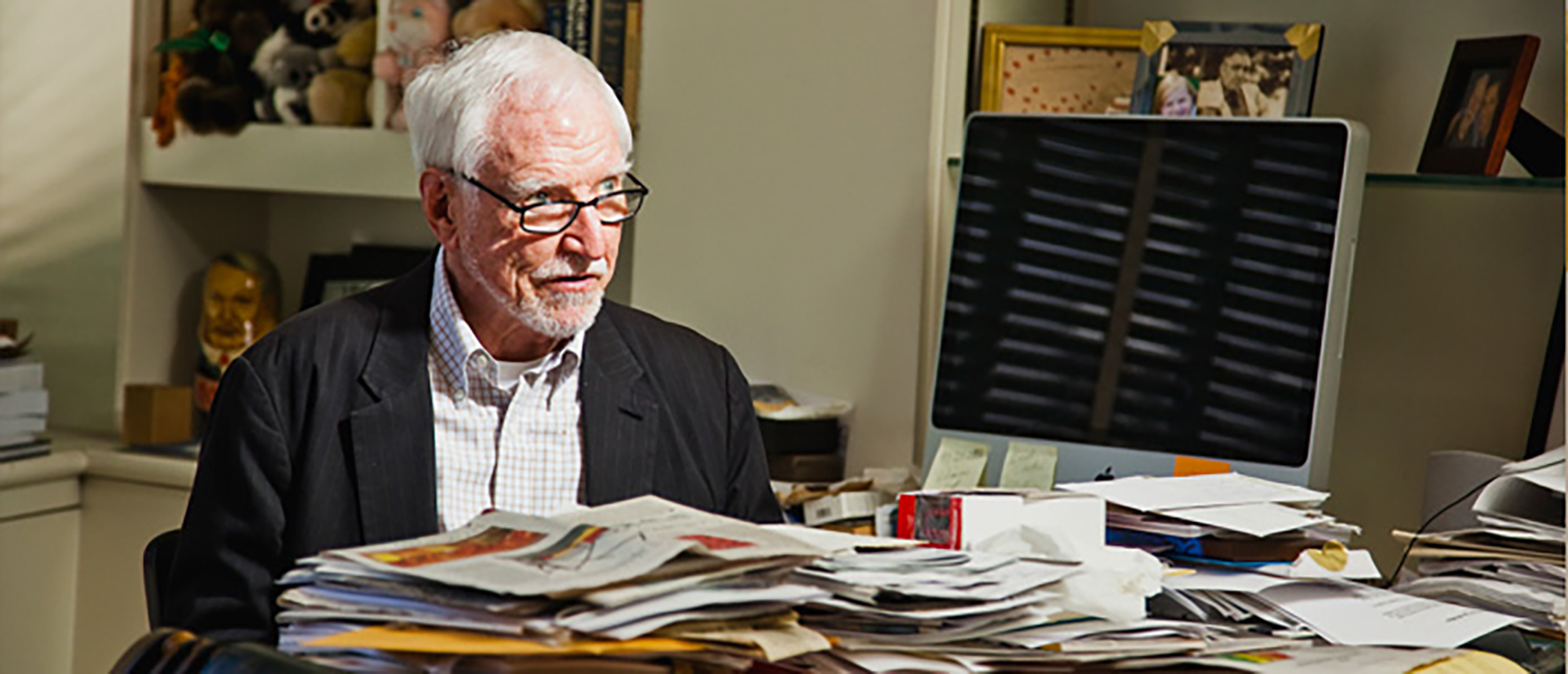

Hormel, in his San Francisco office, didn’t run for Congress but did enter public service. (Photography by Edward Caldwell)

James Hormel, JD’58, spoke at the Law School in January about how he began a new life.

After his 1966 divorce and his wife’s remarriage, James Hormel, JD’58, felt his ties to Chicago loosening. With trepidation, he told his two brothers he was gay; they took the news in stride. Soon after, he stepped down as the Law School’s dean of students and moved to New York to begin a new life. “While not so direct in coming out to other people, I started to conduct myself in a way that would let them make assumptions about me,” Hormel writes in his memoir, Fit to Serve. “I tiptoed out of the closet and found that the more open I was, the more confident I became, and the easier it was to be out.”

Hormel left New York for Hawaii and later San Francisco. In 1978, spurred by a proposed ballot initiative that would have barred gay people from teaching in California schools, he threw himself into the nascent movement for gay rights. Two years later Hormel helped launch the Human Rights Campaign Fund and began to raise and donate funds for civil-rights causes.

As a scion of the Hormel Foods family—the makers of Spam—he had formidable financial resources to give. At first his contributions were anonymous. But at the height of the AIDS crisis, Hormel realized that public philanthropy could attract other donors to projects he supported, so he attached his name to gifts and a pink triangle pin to his lapel. “It felt good to let people know who I was and what I stood for,” he writes. “It took away the power of others to define me.”

As the one-time Republican deepened his involvement in Democratic Party politics, Hormel was determined to blaze a trail for gay public servants. He won two United Nations appointments during the Clinton administration and actively sought an ambassadorial post. After a bitter two-year battle with conservative opponents to his nomination, Hormel was sworn in as US ambassador to Luxembourg in 1999. His children, grandchildren, brother, and ex-wife—all of whose support, he says, was “unwavering”—attended the ceremony.

At 79, Hormel is proud to have served as the first openly gay US ambassador, but he regrets not going public sooner with his orientation. As dean of students at the Law School, he says, “I felt very constrained to keep my sexuality from being known, … and I look back at that and think it was a mistake.” If law students struggling to come to terms with their own sexuality had known they could confide in him, he believes, he could have provided support.

Returning to the Law School this past January, Hormel got the chance to share his experiences with a new generation. Students packed a lecture hall for his lunchtime talk and peppered him with questions about his past, present, and future advocacy. How, for example, was he received in Europe as an openly gay diplomat? What did he think could be done about bullying of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth? How did he reconcile his view that every gay person should come out with the idea that one’s sexual orientation is essentially private?

“If you want to move forward on social issues, you have to endure a certain amount of exposure,” Hormel replied. Sexual orientation is “nobody’s business, but we’ve made it our business because of our laws and attitudes.”

Looking ahead, Hormel plans to focus his activism on public-education efforts, because he believes that cultural attitudes must change along with laws that extend equal rights to minority groups. Even if same-sex marriage were legal in 50 states, he says, intolerance and discrimination would persist. Gay or straight, “we need to understand and accept each other as fellow human beings. And until we do that, then all of the laws in the world aren’t going to make our lives a great deal better.”