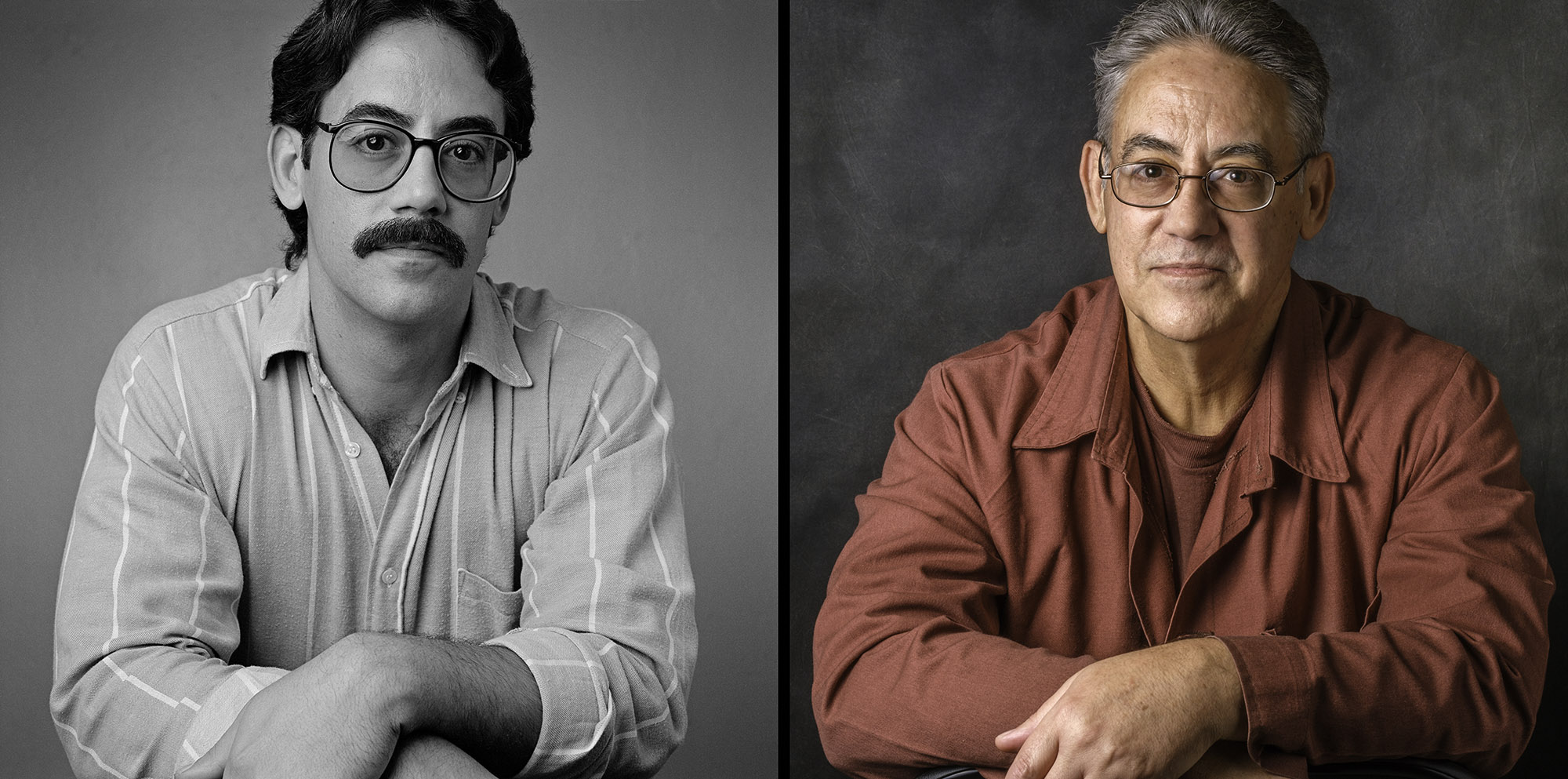

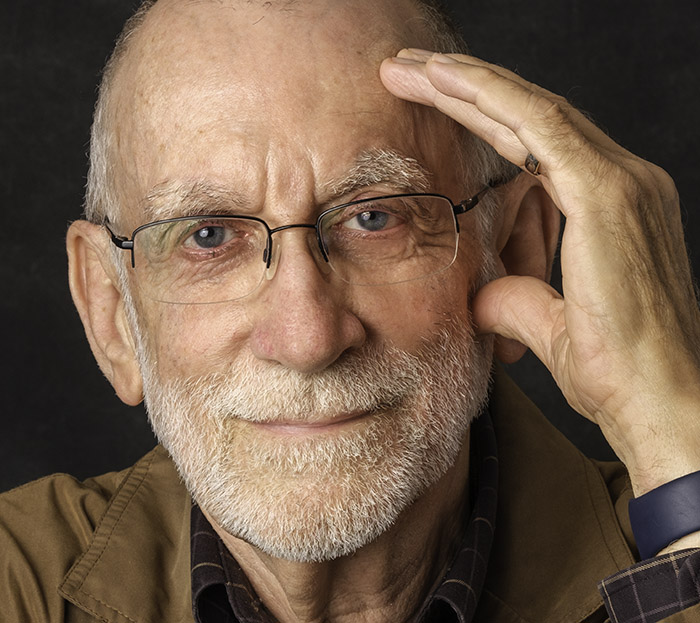

Howard Zehr, AM'67, united his criminal justice reform work and passion for photography with this portrait series featuring people serving life sentences. Zehr photographed his subjects in 1996 and again in 2021 for the books Doing Life and Still Doing Life. (All photography by Howard Zehr, AM’67)

The “grandfather of restorative justice” looks back on a career spent advocating for change.

In 1978 Howard Zehr, AM’67, was asked to lead a new program in the Elkhart, Indiana, probation department. The Victim Offender Reconciliation Program, as it came to be called, facilitated conversations between crime victims and offenders.

Zehr was wary. As a scholar of crime and an advocate for criminal justice reform, he felt uncertain about working inside the machine he had spent years critiquing. He worried, too, that spending time with victims would make it more difficult for him to fight on behalf of offenders trapped in what he saw as an unjust system.

Witnessing the conversations changed Zehr’s view of criminal justice. The Elkhart program focused on crimes such as burglary that are considered nonviolent, but Zehr noticed that many victims experienced burglary as a violent crime. They felt violated, and they wanted answers. Why my house? Why that day? If I had walked in, would you have killed me? Are you sorry? Courts, which focus on determining guilt and handing out punishment, offer no time for such questions.

The criminal justice system didn’t just fail offenders, Zehr realized. It failed victims too. The conversations taking place in Elkhart did what the legal system couldn’t: they allowed victims to express their pain and offenders to reckon with the harm they had done. The program “shook up my world,” Zehr says. “That’s when I began to rethink everything I thought I knew about justice.”

He saw in victim-offender interactions the beginnings of a new approach to harm and its aftermath that he later called restorative justice—a process that, in his words, aims to “collectively identify and address harms, needs, and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible.”

Zehr has been called “the grandfather of restorative justice” and is proud of the label, but quick to qualify it. The idea of accountability through conversation has deep roots: many Indigenous groups around the world have for centuries used community dialogue to resolve conflict. Zehr sees himself not as an inventor of restorative justice but rather as a communicator on its behalf.

Zehr has always been a talker. Growing up in Indiana, he was a ham radio enthusiast who spent hours chatting with new friends from around the world. “I was learning to network—a skill which would turn out to be vocationally important,” he wrote in a recent essay.

Zehr’s commitment to justice and compassion has even deeper roots. He was raised in a socially conscious Mennonite household, and his family’s life centered on faith. Zehr’s father, Howard Sr., was a pastor, and his mother, Edna, wrote articles for the Mennonite publication Christian Living.

Howard Sr.’s work introduced Zehr to figures including Vincent Harding, AM’56, PhD’65, also a Mennonite minister. Harding, who would go on to write several of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches, stayed with the Zehrs several times. “I have a very distinct memory,” Zehr says, “of sitting at the dining room table while Vincent tried to help this naive White kid understand something about racial justice.”

But Zehr knew understanding was less important than doing. The Mennonite tradition emphasizes “taking Jesus’s word seriously for action in the world,” Zehr explains, “as opposed to just believing things.”

So, shortly after enrolling at Goshen College in the early 1960s, Zehr decided that transferring to a historically Black institution was the right way for him to concretize his commitment to anti-racism. He applied to Morehouse College and was accepted.

There were a handful of other White students at Morehouse, but most enrolled for a single exchange semester and were seen by the rest of the student body primarily as interlopers. Zehr worked hard academically to show he was taking the experience seriously and tried to absorb as much as he could about race, racism, and privilege. He found a mentor in the college’s president, Benjamin Mays, AM 1925, PhD’35, who helped Zehr secure a scholarship from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund—“as a minority student,” he notes wryly.

After Morehouse, not knowing what else to do with himself, Zehr enrolled at the University of Chicago for graduate school in history. His master’s thesis, later expanded into a doctoral dissertation at Rutgers University and then a book, was a statistical analysis of crime in France and Germany in the 19th century. (Crime and the Development of Modern Society: Patterns of Criminality in Nineteenth Century Germany and France was rereleased in 2020 by Routledge. “Apparently,” Zehr says, sounding as surprised as anyone, “it became kind of a classic in the history of crime and the use of quantitative materials.”) In 1971 he joined the history faculty at Talladega College, a historically Black liberal arts college in Alabama.

While teaching at Talladega, Zehr became involved with legal defense work and prisoners’ rights efforts—natural outgrowths of his religious commitments, academic expertise in crime, and anti-racism efforts. In 1978, needing a change from teaching and feeling more drawn to social justice work, Zehr decided to leave academia and move back home to Indiana. After a short period directing a halfway house, he began leading Elkhart’s Victim Offender Reconciliation Program.

He spent the next four decades working to articulate and advance restorative justice, first through the Mennonite Central Committee, the church’s peace and relief organization, and then as a faculty member at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. He wrote about “RJ,” as it came to be abbreviated—his book Changing Lenses: A New Focus for Crime and Justice (Herald Press, 1990) is now in its third edition—taught it, and helped policy makers around the world implement it.

He consulted with leaders in New Zealand, for example, as they overhauled the country’s juvenile justice system and devised a new process that blends restorative practices and traditional Maori approaches to conflict resolution. Under the updated system, if a young person is accused of a serious crime and doesn’t deny it, they are typically referred by the Youth Court to a family group conference—a structured meeting involving the offender and his or her family, social workers, and police, as well as victims and their supporters. The conference results in a series of recommendations for how the offender can make amends. Defended hearings—akin to a trial—are generally reserved for cases where the offender denies guilt.

To Zehr, this best-of-both-worlds approach allows restorative justice to focus on victims and their needs, and the Western legal tradition to do what it does best: adjudicate guilt and innocence. Other restorative justice proponents take a different view and would prefer to see restorative approaches sit outside of—or even replace—police, courts, and prison.

However victim-offender dialogues happen, they can be powerful for all involved. Sometimes the conversations help offenders experience true remorse for the first time; Zehr remembers the case of a serial rapist who said that talking to one of his victims allowed him to understand the ramifications of his actions in a way that neither prison nor therapy had done. Often, by meeting offenders, victims can let go of fears they’ve carried for years.

Over the past decade, restorative justice has become something of a buzzword, leading to misunderstanding and misuse. Ironically, Zehr, who was initially so nervous about working with crime victims, finds that many programs billed as restorative don’t focus enough on victims and their needs. Because restorative justice is often proposed from the left and by advocates of criminal justice reform, it is sometimes dismissed as soft on crime and offenders. But being less punitive, in Zehr’s view, isn’t the same thing as being soft: many offenders describe meeting with victims as painful—and a form of punishment in itself.

Alongside these misinterpretations, Zehr also watched his ideas grow in unexpected ways. He learned recently that the Smithsonian Institution has created a Center for Restorative History that partners with people and communities who have been harmed by their portrayals in museums or simply excluded from them. His students and mentees have “gone on and taken it to whole new arenas that I never even imagined,” Zehr says, “far surpassing anything that I would have done.”

Since 2013, when he retired from teaching, Zehr has intentionally taken a less active role in the restorative justice movement. Instead he’s been focused on other interests while he allows a new generation to carry the work forward.

Zehr has always loved photography and found ways to incorporate it into his work; his books Doing Life: Reflections of Men and Women Serving Life Sentences (Good Books, 1996) and Still Doing Life: 22 Lifers, 25 Years Later (The New Press, 2022) feature portraits of prisoners serving life sentences. Now he’s begun doing volunteer work as a hospice photographer. He’s still writing—mostly technical articles for ham radio operators, a welcome return to his childhood hobby.

Zehr borrows a phrase from the writer Barry Lopez in describing his current outlook: “Hopeful, but not optimistic.” He has seen criminal justice reform efforts wax and wane and interest from politicians come and go. Ultimately he thinks smaller-scale, community-based programs have the best chance of promoting accountability and healing in the aftermath of crime.

The tension between optimism and realism has been with Zehr from the beginning. In the afterword to Changing Lenses, he admitted that he sometimes found his own ideas impossibly utopian when considering “my own anger, my own tendencies to blame, my own reluctance to dialogue, my own distaste for conflict.”

But, he went on, “I believe in ideals. Much of the time we fall short of them but they remain a beacon, something toward which to aim, something against which to test our actions. They point a direction.” We can always decide which way to walk.

What is restorative justice?

In a 2014 interview, reprinted in the forthcoming book Restorative Justice: Insights and Stories from My Journey (Walnut Street Books), Zehr summarized his vision for restorative justice.

The criminal justice system tends to ask three questions:

- What laws were broken?

- Who did it?

- What do they deserve?

Everything focuses around making sure offenders get what they deserve. That is usually punishment.

There is nothing for the victim because the victim isn’t really a part of the criminal justice system. The crime is considered to be against the government, against the state.

Restorative justice changes the questions. It asks:

- Who’s been hurt in the situation?

- What are their needs?

- Whose obligation [is it to address those needs]?

Restorative justice focuses on needs and obligations and not so much on what the offender deserves. The victim is just as important as the offender in this process.

Restorative justice turns the situation so that the victim’s needs are addressed and the offender’s obligations are discussed and worked with. The whole concept is based on the reality that we humans are rooted in relationships, and that relationships matter.