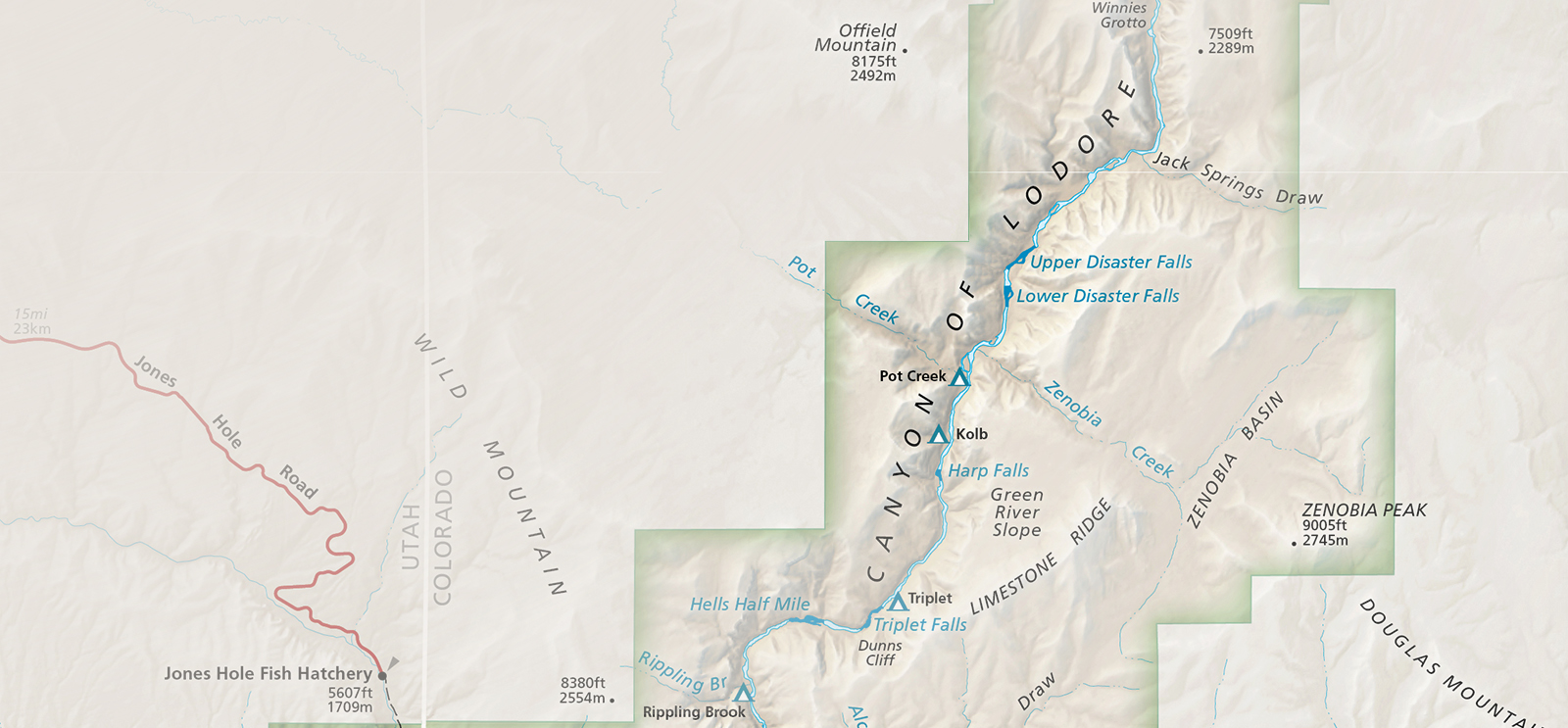

(Map courtesy National Park Service)

Grieving father Stéphane Gerson, AM’92, PhD’97, seeks comfort in historical writings and family stories.

On a family trip, Stéphane Gerson, AM’92, PhD’97, lost his young son Owen when their kayak capsized on Utah’s Green River. Gerson’s new book Disaster Falls: A Family Story (Crown, 2017) chronicles how he; his wife, Alison; and their older son, Julian, each in their own ways, navigated the devastating loss and the unfamiliar world it created. Gerson, a cultural historian, grieved in part by writing about Owen. This act of writing “felt like an affront ... inadequate, unjust, and intolerable. But it was less inadequate, less unjust, and less intolerable than silence.”

Gerson also read, turning to stories from the past—writers mourning lost children and his own family history. In the chapter excerpted here, he reflects on how those historical voices helped pierce the solitude of grief.

The people for whom I longed—available whenever I needed them, still open to the world, ready to share their experiences without expecting me to reciprocate—did not exist, at least not anywhere I could see. To find such bereaved parents, I had to canvass other centuries. An important part of my mourning that first year took place in eras other than my own.

I had begun with [poems by] Victor Hugo but found others. In the Renaissance, the astrologer Nostradamus lost his wife and two children to the plague epidemic that devastated Provence in the 1530s. While he mourned them privately, this ordeal allowed him to touch and capture in poetic prophecies the suffering and disquiet that so many of his contemporaries felt during those tumultuous times. Across the English Channel, Ben Jonson and Shakespeare expressed their sorrow for their departed sons in harrowing verses. “My sin was too much hope of thee, loved boy,” Jonson wrote. “Seven years thou wert lent to me.” Shakespeare included a bereaved mother in King John, the first play he wrote after his son’s death in 1596. “Grief fills the room of my absent child, / Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me.”

While some of these bereaved parents had attained fame, most were ordinary folk who had left a record of their suffering. Around 1800, a Burgundian notary by the name of Jean-Baptiste Boniard lost two of his children, including his five-year-old daughter Adèle, who succumbed to scarlet fever. He kept a detailed account of his last conversation with the girl, the “rosebud” who liked to kiss and comfort her father and died while reciting a fable to him. I found this out by chance, while reading the reminiscences of his grandson. Boniard was a fascinating character (local politician, journalist, amateur archaeologist and astronomer), but his relationship with his late daughter told me everything I wanted to know about him.

Decades later, Victorian parents mounted images of deceased children on matchboxes with “lovely little scrolls” and snippets of hair. Charles Darwin kept objects that had belonged to his daughter Anna, as well as her writings, in a box that he built. The English widower John Horsley said he felt better when he wrote about the four sons and daughter he had lost to illness. The American Henry Bowditch, father of a soldier who died in Virginia in 1863, recovered his son’s body and then compiled memorial volumes and scrapbooks about his life. This is not how men were expected to grieve. Bowditch understood this, but he maintained his course. “The labor was a sweet one,” he wrote. “It took me out of myself.”

And the Englishwoman Janet Trevelyan—she wrote everything she could recall about her son Theo after his death in 1911: “I know that as we get further from the pain of these last days the pure joy and beauty of his little life will shine out more and more and will be like a light in our hearts to illuminate the rest of our way.”

My investigations of the past were in character: as a historian, this is what I had done every day for years. Uncovering such narratives, memorials, and poems came instinctively, proof that some part of my professional self remained intact.

But there was nothing scholarly about this exploration, no questions to resolve about grief across the centuries. Historians are wary of their biases and tend to keep their emotions and proclivities at a remove from their research. I now found this impossible. It was companionship I sought. I wanted to know these men and women who, as Horsley put it, kept “the uncertainty of this life ever in view.” They inhabited a realm of pure emotion and allowed me to join them, to mourn in their company whenever I so desired.

W. E. B. Du Bois had faced uncharted expanses upon burying his son, in 1899. “It seemed a ghostly unreal day—the wraith of life,” he wrote. “We seemed to rumble down an unknown street.” Granville Stanley Hall, the American founder of gerontology in the 19th century, felt that the death of his daughter by gas asphyxiation was “the greatest bereavement of my life—such a one, indeed, as rarely falls to the lot of man.” Hall was 44, but this great fatigue, as he called it, made him feel much older. I rumbled down unknown streets with Du Bois and Hall, prey to a great fatigue that made me feel as old as they had.

Except for those Hugo poems, I did not tell Alison of my explorations. I did not require her presence alongside men and women with whom I could commune day and night, all of us part of a community that remained perpetually accessible.

This quest also took me to World War II, with its untold number of dead children. For Jewish parents in Nazi-occupied Europe, the loss of a child was both swallowed up and magnified by the attack upon entire communities. The Polish shoemaker Simon Powsinoga withstood one form of degradation after another in the Warsaw Ghetto, but not the death of his only son. “Two days ago I was still a human being, … I could support my own family and even help others,” he said in the midst of the war. “I just don’t care now. I don’t have Mates, what’s the point of living?”

This despair provided little succor, but there was no way around World War II in my family. My childhood in Brussels had been colored by the story of my maternal grandparents as a young couple during the war. I had always viewed Zosia and Jules as embodiments of History. When I was a child, their everyday lives seemed normal enough. They dressed in the morning and ate breakfast as I did; they walked on the same sidewalks; they gossiped and quarreled and laughed like everyone else. But they had experienced something I had not; their proximity to danger and death had made them different kinds of people.

Zosia had grown up in an affluent Jewish family in Warsaw. Her father, a silk merchant whose business took him to France and Belgium, was sufficiently lucid about the rise of anti-Semitism to move his wife and children to Brussels in 1932. It was there that Zosia met Jules, a diamond trader who would see action as a Belgian conscript in 1940 and then spend a year in Germany as a prisoner of war. They married in March 1942, and left for Southern France two months later. The French collaborationist regime in Vichy, and especially the Italian troops that controlled the city of Nice, seemed more forgiving than the Nazis who occupied Belgium. After an epic journey by train, bus, and foot, my grandparents arrived in Nice and registered as foreigners with the French police. Afterward, they rented an apartment and plotted their next step. My grandmother was pregnant.

When Owen died, Jules was long dead and Zosia in the throes of dementia. And yet one of the first things I did, without awareness, was to summon them to my side. I did so on the river, when I recited the Shema in their company, and back home, when I returned to their wartime story. Although my grandparents had been dehumanized and persecuted, although our experiences were by no means similar, we could now enter a different realm of existence and encounter together shock and sorrow, and perhaps resilience. There was empathy, too. My grandparents knew too much about human frailty and the contingency of everyday life to ask me the kinds of questions I was asking myself, such as, How could you have allowed this to happen? How could you have let Owen go?

The accident changed something else in the way I saw my grandparents. After all, they had survived the war with their infant daughter—my mother.

Shortly after arriving in Nice, they were arrested by the French police and sent to the detention camp of Rivesaltes, near the Pyrenees mountains. They were unlikely to remain there for long. With the Germans about to take possession of Rivesaltes from the French, prisoners were being transferred to other camps or deported to Auschwitz. Zosia wrote to an official whom she had met at the Nice police station and asked him to intervene. He did. My grandparents were freed in November 1942. They returned to Nice, where my mother was born a month later.

The official, Charles, remained present in their lives. He warned them about imminent arrests and helped them find an apartment. He also introduced them to his wife, Annie. The two couples sometimes socialized, strolling together in public parks and posing for snapshots. In one photograph, Annie and Charles cozy up with Zosia on a bench, like long-lost cousins. In another, Annie cradles the swaddled baby in her arms. The child remains at the center of things. Annie and Charles kept her for several months in the fall of 1943, when massive roundups of Jews forced my grandparents into hiding. My mother’s first name, Francine, serves as a tangible reminder of this time and place—France and Nice intermingled. Her middle name is her godmother’s: Annie.

Why had Charles helped this couple while, I assumed (rightly or not), stamping papers and contributing to the bureaucratic machine of identification, surveillance, and deportation? After the war, my grandmother made allowances and expressed gratitude for the man who had saved their lives, but never spoke much about his wife despite the risks she had taken. While my grandparents often vacationed in Nice, they only introduced my mother to her godparents twice, once when she was five and once when she was 17, in 1959.

It may be impossible to know what transpired among the four of them, but this did not stop me from conjuring up scenarios after Owen’s death: a social divide, infidelity or attraction, shame, jealousy, competing affections for the baby. At some point, it dawned on me that my grandparents might have kept a distance from a couple who reminded them of their interrupted youth and a truth that is not always easy to accept: how much we owe to others when our life veers out of control.

My mother could not understand why I asked her for more information about her parents and the war. It’s a simple story, she said, and she may have been right. But I saw complicated and perhaps conflicted human beings whose behavior transcended the binary categories—in this case rescue and collaboration, justice and ingratitude—with which we all too often make sense of the world. Ultimately, it was impossible to determine what a savior looked like, or who exactly had saved whom.

Zosia seemed to understand these ambiguities. “Things are never entirely positive,” she once told me regarding Charles, “and they are never entirely negative either.” In this respect as well, my grandparents—the grandparents I imagined—provided solace and companionship. Together, we could escape the expectations of others and absolute conceptions of virtuous behavior.

But for how long? When Zosia recalled her wartime years, she described Jules’s forays into the black market. On some days, he would return with bananas for the baby, and only for the baby because that is all they had. She also depicted herself as an ingenious woman who made her own luck, took risks, and never allowed fear to hold her back. She had reached out to Charles as he sat behind his desk; later, she had written him from Rivesaltes. Someone had saved my grandparents, but according to this family story, they, too, had saved themselves and their daughter.

So, the three of us did not inhabit the same realm, after all. My grandparents were not only rescuees, but also rescuers and parents who had fulfilled their responsibilities. Luck had played its part, but this was not the main takeaway. Their story could not be mine.

Stéphane Gerson, AM’92, PhD’97, is a cultural historian and a professor of French studies at New York University. A recipient of the Jacques Barzun Prize in Cultural History and the Laurence Wylie Prize in French Cultural Studies, he lives in Manhattan and Woodstock, New York, with his family. Reprinted from Disaster Falls: A Family Story. Copyright © 2017 by Stéphane Gerson. Published by Crown Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.