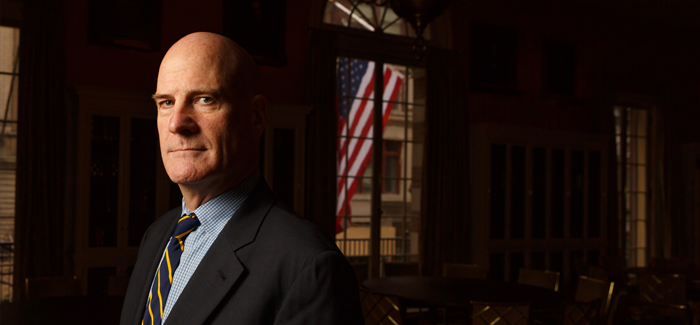

Grant McCracken worked with Netflix to analyze television binge watching. (Photography by Jason Smith)

Canadian anthropologist Grant McCracken, AM’76, PhD’81, has built an unconventional career as an observer of American culture.

Culture—which Grant McCracken, AM’76, PhD’81, defines as the body of ideas, rules, emotions, and activities that make up the lives of consumers—is a powerful force. It’s so powerful that corporations should hire an in-house expert to study it full time, he argues in Chief Culture Officer (Basic Books, 2009). McCracken also has suggested that anthropologists parlay their knowledge of culture into careers that reach beyond the academy, something he’s done as a consultant, speaker, curator of the blog cultureby.com, and author of nine anthropological books.

After directing the Institute of Contemporary Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum, McCracken taught at Harvard Business School and MIT. His latest book, Culturematic (Harvard Business Review, 2012), examines entrepreneurs and inventions—from Rube Goldberg to reality TV—that have shaped contemporary culture. This past year he was an affiliate of Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society and a consultant to Netflix, binge watching TV shows like Scandal and Breaking Bad—for work, of course.

Dialogo’s interview with McCracken is condensed and edited below.

Why did Netflix hire you in 2013?

Netflix has perfect quantitative data, so they know how many people are watching what TV shows at what time, at what intervals. They could tell that people were sitting down to watch 12 episodes of a season over a week, or bingeing, as they called it. But what their data didn’t tell them was what, why, and how, and that’s when they send in the anthropologist.

I did my ethnographies and found that bingeing is the wrong metaphor, if we mean people stupefied by the boob tube and mesmerized by bad TV. The reality is something else: people are watching good TV with a kind of passionate and critical engagement, where they second-guess casting decisions and camera angles and take almost a practitioner’s pleasure in observing how the thing is crafted, even as they are caught up by the craft. To put it simply, as consultants are obliged to do, I said, “It’s not bingeing; it’s feasting.”

What are the broader implications?

I’m looking at what that change in TV viewing tells us about a general change in how people consume culture. If there’s been a TV revolution, then we are obliged to see that consumers are more intelligent, more engaged, more observant, more appreciative of good work, and more disdainful of bad work. I’m working on a book about what this means for the “creatives” who produce culture, and for marketing in general and branding in particular.

You describe yourself as a freelance anthropologist. What are the advantages of this approach over a traditional academic career?

I wrote a sustained answer to that question in an essay called “How to Be a Self-Supporting Anthropologist,” published in A Handbook of Practicing Anthropology (Wiley, 2013). For me, the academic world proved a gravitational field that influenced too much the way I thought about myself, what I did professionally, the problems I thought were urgent, the choices I made in new research projects. That gravitational field holds everybody in its thrall, and many anthropologists congregate around the same topics, I think, to the detriment of the discipline.

My work has gone off in unconventional directions, but I think it’s good for the field to try to oxygenate intellectual practice in this way. The big advantage of being self-sustaining—using the proceeds from consulting work to sustain your own academic inquiry—is precisely that you stop congregating and begin choosing your own topics and problems.