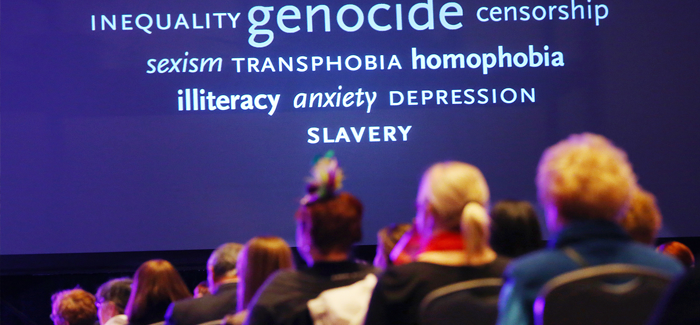

Activist Andrew Slack speaks to the crowd at the ALA President's Program in January about his work with the Harry Potter Alliance. (Photography courtesy the ALA, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Twitterocracy

Cathy Cohen examines the ever-shifting political landscape.

In her talk “Remaking Democracy in the 21st Century: New Media Participatory Politics and Race,” Cathy Cohen, the David and Mary Winton Green Professor of Political Science, set out to explore a timely topic: whether “participatory politics” might alter some of the conventions of American politics. In addition to the mid-October presentation to the Women’s Board at the University Club that I attended, Cohen spoke on the same topic at the Chicago Humanities Festival. She focused on the ways people engage in politics through new and digital media (referred to as participatory politics), the standards of digital equality, and how participatory politics serves as a tool particularly for young people of color.

Technology and politics go hand-in-hand, from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats to the first televised political debates. Does the ascendant role of new media, such as the use of Twitter during political uprisings, signal a new transformation in American politics? Already anyone with digital skills can bypass the editors and publishers who used to be gatekeepers and share news and opinions beyond their neighborhoods and friends.

Cohen cited the nonprofit fan activist group Harry Potter Alliance as practicing participatory politics through social media: in response to the 2010 earthquakes in Haiti, the group used Twitter to promote fundraising for relief and ultimately sent five cargo planes of supplies to the country. However Cohen was cautious not to overstate the positive effects of participatory politics. “It’s not clear if participatory politics will lead to sustained mobilization,” she said, referring to the Occupy Movement, where many individuals participated but few maintained deep ties.

Cohen found that inequalities exist even just in terms of internet access. She showed research demonstrating that on average, white youth have better broadband access and knowledge about the internet than their black and Hispanic counterparts, and that black youth are more likely to engage in friendship-driven activities online versus the interest-driven activities that attract more white and Asian youth. Does that mean that ultimately, those who could be most empowered by the internet are not taking advantage of the opportunity?

Moreover, many black youth still see themselves as politically alienated, despite the fact that this generation, Cohen noted, is presented with the greatest opportunity for advancement of any generation of black Americans, with black officials in power and no harsh realities of Jim Crow laws. Cohen showed disturbing video clips showing black youth being harassed or abused by police officers, including the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. She noted that while the ability to raise awareness of these events online is a method of participatory politics, it can also reinforce feelings of powerlessness and disenfranchisement among viewers.

Cohen wrapped up by pointing out some ways that a new digital public sphere can still be improved to foster new types of political equality. For instance, many public and charter schools shut down access to the web during the school day to keep students focused on their classes, one consequence is that it blocks their ability to engage in participatory politics. Ultimately, Cohen said, participatory politics provides an opportunity for a new infrastructure where young people can create a public space where political equality is exercised. “True embrace of participatory politics means rethinking what counts as equality.”

Video

Professor Cathy Cohen discusses the Black Youth Project, what it reveals about black Americans’ experience, and the political repercussions of these findings as part of the 25th Chicago Humanities Festival.