Jack Schultz, AB’50, with the Sea Fever. (Photo courtesy the Mariners’ Museum and Park)

At 18, Jack Schultz, AB’50, began a journey that set the course for the rest of his life.

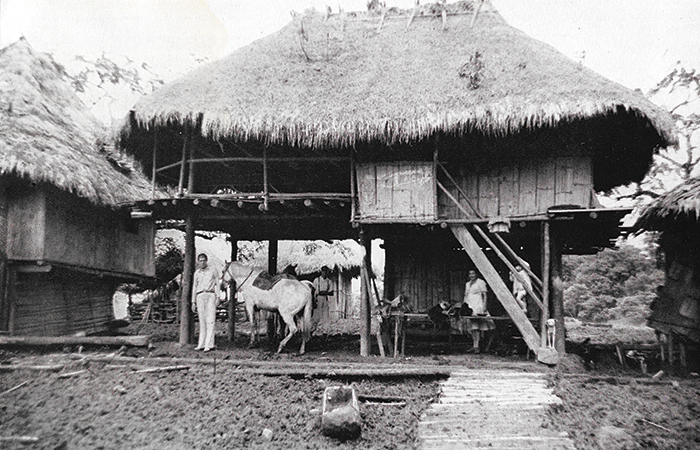

In May 1947, Jack Schultz, AB’50, decided to make his way back to UChicago from his family’s home in Quito, Ecuador. After a lift to the end of the road he set out alone, hiking east over the Andes, paddling down the Amazon, then sailing across the Caribbean to Miami. Schultz doesn’t remember how he made the final leg of the journey to Chicago: “I think I probably hitchhiked,” he says. “I always loved hitchhiking.”

But why? “Because it’s there” is the most famous answer to that perennial question: a quip attributed to English mountaineer George Mallory, who tried to climb—and later died on—Mount Everest.

It was a poem that inspired Schultz’s journey, according to “Sea Fever,” a first-person account in the February 1949 issue of National Geographic: “I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky…” The poem, by John Masefield, also inspired the name of Schultz’s second boat, the Sea Fever.

A romantic story and not exactly true. The real reason for his travels, says Schultz: “I was a rootless 18-year-old with no status in the world.” Now 93, Schultz is working on a memoir about his experiences—but not the swashbuckling adventure version. He’s trying to get at something deeper.

Schultz comes from a family of adventurers, although “they wouldn’t think of themselves that way,” he says. His father, an early aviator, served in World War II in his mid-forties and was killed in China. His parents had been divorced for some time; his mother had moved the family from Miami to Quito, where she ran a hotel catering to Americans.

Schultz enrolled in the Hutchins College in 1944 at age 15. When he began his journey back to school, hiking a mule trail that reached elevations of 13,000 feet, he intended to reach Chicago by Autumn Quarter 1947. In fact, it took more than a year to reach Miami.

Schultz bought his first canoe at the headwaters of the Río Napo, a tributary of the Amazon. He named the dugout canoe, which was 16 feet long by 16 inches wide, the Lizzie, after his Chicago girlfriend. Farther down the Amazon, in Iquitos, Peru, Schultz paid about $11 (a little more than $135 today) for a larger canoe made by stretching a soft cedar log over a fire rather than by hollowing it out. The Sea Fever, almost four feet across, had been made from a log just two and a half feet in diameter.

In Manaus, Brazil, a carpenter helped him fortify the canoe for an ocean voyage, raising the sides and adding masts for sails. Some experienced sailors—horrified by Schultz’s plan to sail the ocean alone with just a pocket compass and a few hours’ sailing experience—gave him how-to books, a nautical almanac, a plastic sextant, and lots of advice.

Unfortunately, “I have never been much good at taking advice,” Schultz wrote in National Geographic. Seven days out, he capsized and lost almost everything. Luckily he was able to save the rubber bag containing the sextant, the books, his passport, and some clothing.

Even before he reached the ocean, there were dangers. In the lower Amazon he was bitten by something in shallow waters—possibly a piranha. He got caught in a tidal bore, a strong tide that pushes up the river; by the time he realized what was happening, it was too late to pull up anchor. Surrounded by a wall of rushing brown water, there was nothing to do but wait and hope to not be killed.

In December 1947 he sailed out into the Atlantic. He meant to sail directly to Trinidad, but an error of navigation brought him to Devil’s Island, the French penal colony. There he received treatment for saltwater boils from the prison nurse—just another example of the kindnesses Schultz received from strangers who supplied food, shelter, equipment, medical care, and the often-ignored advice all along his journey.

“I tell people for shock value,” Schultz says, “I died on the boat.” One day he was terribly hungry and had caught a shark, using his last morsel of food as bait. But the shark cut through the line and got away. “I found myself out of my body, looking down at my body in the boat,” he recalls. “That was one of the most desperate, desperate times I ever felt. And then—not feeling any special emotion—I decided to live.” Two days later, he landed on Trinidad.

By the time Schultz arrived in Miami, he was already a minor celebrity; local newspapers had been writing about him along the way. National Geographic commissioned an article, but he struggled to produce more than a few pages. Finally, the magazine flew him to its offices in Washington, DC, where he sat in a room with a stenographer for three days, dictating his story.

After the article appeared, publishers were interested. Schultz tried to write—but never completed—a book-length version. Speaking about the experience was easier. Schultz traveled the country giving lectures; the Executives’ Club (a club for businesspeople, similar to the Rotary Club) was a major client. “People want to hear this sort of adventure stuff,” Schultz says. “I was professionally entertaining. There’s a great temptation to exaggerate, but I tell people I try never to lie about the same thing twice.”

In 1952 Schultz gave up his speaking career to train as a carpenter. In the mid-1950s, he worked as a firefighter while studying physics at San Diego State University. Later he became an engineer and built many custom homes (including his own).

But he never lived an entirely staid life. In the 1960s he organized and led an expedition to study migration patterns of nursing gray whales. More recently he sailed around Bali, where one of his sons was living. “That doesn't sound like much, but it happens to be very difficult sailing conditions,” he says. “I'm sort of proud of doing that.”

The bite on his leg healed quickly, not leaving much of a scar. He recovered from the saltwater boils as well as malaria, sustaining no serious physical injuries. “My biggest illness,” says Schultz: “I suppose you could call it PTSD. After all these years, it affects me.” The feeling is physical rather than emotional: “sort of like being cold all over,” he says. “It goes away. I hold onto it if I’m trying to write, but otherwise I just get my mind off it pretty quick.”

His best writing time, Schultz says, is about an hour before dinner. With encouragement from his wife, Linda, he’s written 70 or 80 pages so far. The work goes slowly because he can’t tolerate doing it for very long.

After years of telling the adventure tale, Schultz struggles to convey a more realistic version of his journey and his complex emotions. Being caught in the tidal bore, for example, which he considers the most dangerous moment, “was like being closed up in a womb. The womb of a woman who’s running in a race.”

Revisiting that moment to try to write about it, “I’ve realized I did not feel a great deal of fear,” Schultz says. “It was beautiful. It was absolutely beautiful. How can I explain the ‘beautiful,’ being surrounded by a wall of water which any second could kill you?”

Six stops along a 6,000-mile journey

1. Quito, Ecuador

The starting point of Schultz’s 6,000-mile journey. He began by walking over the Andes on May 11, 1947.

2. Iquitos, Peru

Here Schultz bought a larger canoe, which he named the Sea Fever.

3. Santerém, Brazil

A novice sailor, Schultz capsized and lost nearly everything.

4. Royale Island, French Guiana

By mistake, Schultz landed on Devil’s Island, a French penal colony. The prison nurse, a former Parisian pickpocket, treated him for saltwater boils.

5. Trinidad

Schultz earned $1,200 to complete his journey by helping blow up mooring dolphins—installed by the US Army during the war—with dynamite.

6. Miami, Florida

Schultz arrived on June 30, 1948. When he asked for directions for entering the country, the official looked at his tiny craft and said, “What the hell do you want to know for? You haven’t been anyplace.”