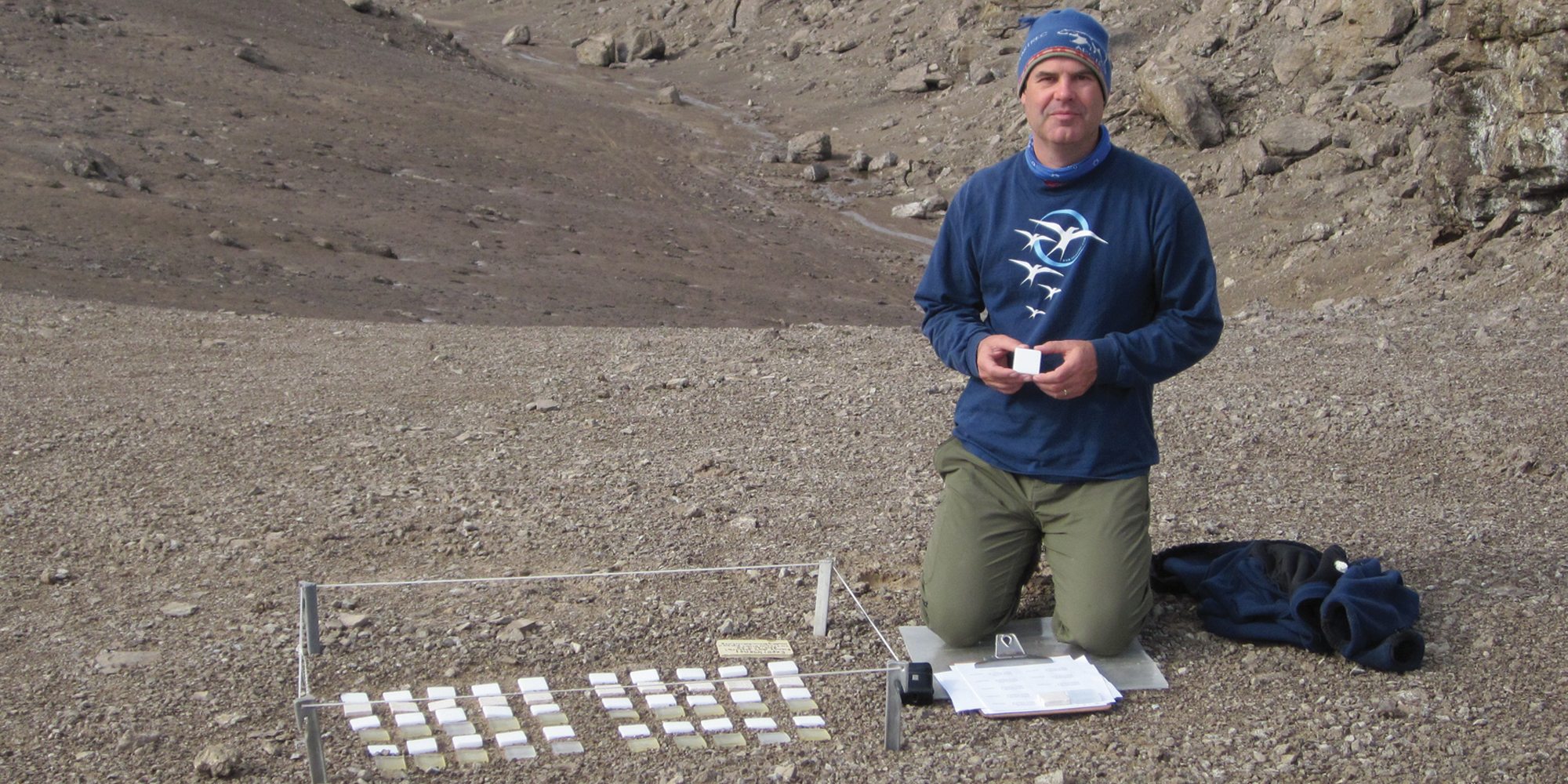

Michael Wing, AB’85, on Devon Island setting out artificial stones. With time, green cyanobacteria grow underneath. “I have sets like this on every continent—10 in total,” says Wing. They’re in extreme environments where not much grows, such as hot deserts, polar deserts, and mountaintops. Nothing can live on the surface of Mars, but maybe microorganisms could survive this way: “Half an inch of rock may be all it takes.” (Photo courtesy Michael Wing)

Michael Wing, AB’85, on his career guide for “the PhD barista.”

Michael Wing, AB’85, thought he wanted to be a professor. But after earning a PhD from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, he walked away from jobs at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in New York and Middlebury College in Vermont. “I can’t even explain it,” he says. “I burned my bridges with academia not once but twice.”

He went back to school, got a teaching certificate, and took a job teaching ninth grade in San Anselmo, California. He liked it but missed doing research. So Wing applied to participate in a study tour of the Galapagos Islands through the Toyota International Teacher Program. “It was totally free,” he writes in Passion Projects for Smart People (Quill Driver Books, 2017). “Toyota Motor Sales paid for everything, including our substitute teachers back home.”

Since then Wing has done field work in Costa Rica, Alaska, Finland, Namibia, India, the United Arab Emirates, the Pacific Ocean, and the High Arctic, all supported by outside organizations. He’s collaborated with NASA and the National Park Service and published his work in peer-reviewed journals. He explains how he’s done it in Passion Projects, “the perfect career guide for the era of the PhD barista,” as the jacket copy puts it.

Wing’s recent passion projects

Canadian Arctic

Wing has an “ongoing loose collaboration” with Pascal Lee of the Mars Institute. Lee does research at Devon Island, which has a “Mars-like geology,” says Wing.

Point Reyes National Seashore, Marin County, California

Wing and a group of high school students surveyed an 800-foot line of granite stones set into the ground, once thought to be prehistoric. They discovered that the small stones were set crosswise and the big stones lengthwise, just like stone walls in New England. Wing concluded the structure had been built by 19th-century ranchers. Wing and two student coauthors published their findings in a 2015 issue of California Archaeology.

White Mountains, California–Nevada border

Wing and his students have done several research projects here. One focused on bristlecone pine trees, the oldest trees in the world. Wing wondered why the grain in the wood twists. So his students measured 600 trees: “Some are righties, some are lefties, some are straighties,” Wing says, with no correlation to their environment. This research was published in the journal Trees: Structure and Function in 2014.

For seven years, Wing and his students grew an alpine garden at 12,500 feet, “like a mock Mars colony,” he says. They succeeded in growing lettuce, radishes, potatoes, winter wheat, garlic, and herbs.

Wing’s current project is a study of stone structures allegedly built by Basque and French shepherds from 1850 to 1950. Not all the structures are shepherds’ huts, he says; others are tent circles or hunting blinds built by Native Americans. He and his students are surveying them to discover which is which.