Adapted from illustrations by April I. Neander, Dorothea Krantz and Oscar Sinisidro, Davide Bonadonna, Todd Marshall, and Kalliopi Monoyios, and a 3-D model by Tyler Keillor.

Meet some of the fantastic beasts UChicago faculty helped introduce to the scientific record and the popular imagination.

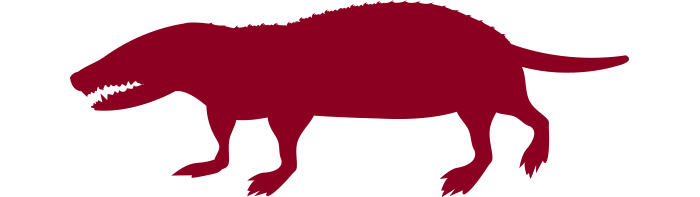

Tiktaalik roseae

Tiktaalik roseae probably looked something like a flattened crocodile. However, the 375-million-year-old fossil, unearthed in 2004, is the key to understanding the evolutionary link between aquatic and land-dwelling animals. Although Tiktaalik had fins and lived mostly in shallow streams, scientists believe it spent short amounts of time on land—its skeleton reveals limb structures present in later land-dwelling mammals, including humans. This concrete connection between humans and prehistoric fish was the subject of a best-selling book and a PBS series, both titled Your Inner Fish.

Site: Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada

Age of specimen: 375 million years (Devonian)

Discovered: 2004

UChicago researcher: Neil Shubin, Robert R. Bensley Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy

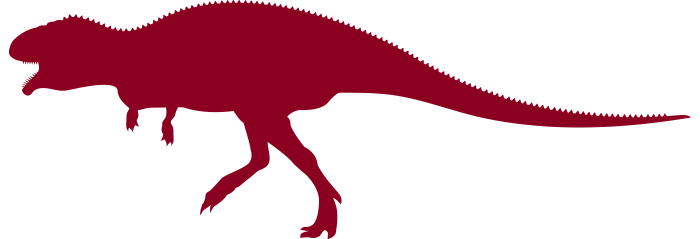

Eodromaeus murphi

Eodromaeus murphi, a 3.9-foot-long carnivorous dinosaur weighing in at a meager 15 pounds, looks tame enough. But despite its small stature—“pint-sized,” in Sereno’s words—the “dawn runner” has had an outsized impact on our understanding of dinosaur evolution. The 230-million-year-old species dates so far back that paleontologists have dubbed it a basal dinosaur: they believe it forms the base of an entire family tree. Its upright gait, sharp teeth, and sharp claws suggest that it was an ancestor to T. Rex.

Site: Northwestern Argentina

Age of specimen: 230 million years (Triassic)

Discovered: 1996

UChicago researcher: Paul Sereno, professor in organismal biology and anatomy

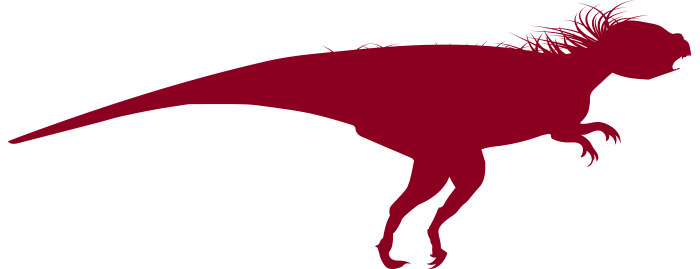

Pegomastax africanus

Rock fans, check your Dinosaur Jr. jokes at the door. Yes, Pegomastax africanus was tiny. The bizarre bipedal herbivore, whose name translates to “thick jaw from Africa,” brandished a beak with a pair of vicious-looking canines and rows of self-sharpening teeth. But it was the bristly hide—found preserved under lake sediment and ash—that led Sereno to liken Pegomastax to a “nimble, two-legged porcupine.” The Pegomastax fossil was discovered in a slab of rock in the early 1960s and tucked away in a Harvard University lab drawer, its significance not yet apparent. Sereno encountered it years later and, he told the New York Times, “my eyes popped, as it was clear this was a distinct species.”

Site: South Africa

Age of specimen: 200 million years (Jurassic)

Discovered: 1960s

UChicago researcher: Paul Sereno

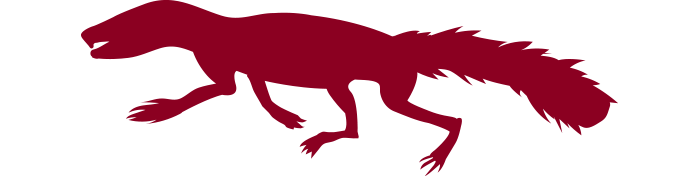

Megaconus mammaliaformis

To be classified as mammals, animals must nurse their offspring. Another typically mammalian characteristic? Fur. But one fuzzy critter from 165 million years ago suggests that mammals may not always have had a monopoly on hair. Squirrel-like Megaconus mammaliaformis had mammalian fur and teeth—but also a spine, ankle bones, and ear structures that closely resembled other mammal-like reptiles. The discovery of the not-quite mammal, not-quite reptile Megaconus proves that many of the traits we associate with mammals today first emerged in other classes of creatures. Today’s mammals are the “accidental survivors,” Luo explains, of many mammaliaform lineages that weren’t so lucky.

Site: Inner Mongolia, China

Age of specimen: 165 million years (Jurassic)

First described: 2013

UChicago researcher: Zhe-Xi Luo

Agilodocodon scansorius

Shrew-like Agilodocodon scansorius dashed up tree trunks and skittered over branches, high above the ground 165 million years ago. The earliest known tree-dwelling mammal, Agilodocodon likely fed on sap, a first for mammals. Its front teeth were shaped like spades, allowing Agilodocodon to chomp through bark, though its sharp-edged molars suggest it may have been omnivorous. Agilodocodon had sturdy, flexible wrists, elbows, and ankles for climbing—structures present in modern climbing mammals.

Site: Inner Mongolia, China

Age of specimen: 165 million years (Jurassic)

Discovered: 2011

UChicago researcher: Zhe-Xi Luo, professor of organismal biology and anatomy

Docofossor brachydactylus

While Agilodocodon scansorius took to the branches, Docofossor brachydactylus was the first mammal to live underground. Similar to African golden moles, these mouse-sized mammals evolved shovel-like paws with short, wide fingers, perfect for digging—suggesting that the gene patterning in modern mammals that causes variation in skeletal development also operated in their long-ago ancestors. Scientists believe that Docofossor favored lakeside dwellings, where it snacked on worms and insects in the soil.

Site: Hebei Province, China

Age of specimen: 160 million years (Jurassic)

Discovered: 2012

UChicago researcher: Zhe-Xi Luo

Spinolestes xenarthrosus

Spinolestes xenarthrosus scurried on wetland floors around 125 million years ago. The “Cretaceous furball,” as Luo describes it, was just under 10 inches long, about the size of a modern-day mouse or rat. (Researcher Thomas Martin of the University of Bonn dispensed with scientific objectivity and admitted to the BBC he found Spinolestes “very cute.”) Despite the fossil’s age, features including compound hair follicles, hedgehog-like spines, and soft tissue were preserved. Because of Spinolestes, researchers now know that these fundamental qualities of modern mammals had already emerged during the early Cretaceous period, some 60 million years earlier than previously thought.

Site: Las Hoyas Quarry, Spain

Age of specimen: 125 million years (Cretaceous)

Discovered: 2012

UChicago researcher: Zhe-Xi Luo

Kryptops palaios

Kryptops palaios—literally, “old hidden face”—owes its name to the spiny shell that enveloped its skull. In practice, Kryptops wasn’t one for hiding: with small, sharp teeth and a taste for carcasses, the 25-foot carnivore was compared to a two-legged hyena by its discoverers. Like Eocarcharia dinops, another fossil discovered on the same dig in the Saharan Desert, Kryptops was indigenous to the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, from which present-day South America, Africa, Arabia, Madagascar, India, Australia, and Antarctica were formed.

Site: Saharan Desert, Niger

Age of specimen: 110 million years (Cretaceous)

Discovered: 2000

UChicago researchers: Paul Sereno and Stephen L. Brusatte, SB’06

Eocarcharia dinops

Eocarcharia dinops—the “fierce-eyed dawn shark”—lived up to its name: standing 25 feet tall, it boasted a maw full of bladelike teeth and a swollen bony brow that wasn’t just for looks: Sereno and Brusatte theorize that the creature used its head as a battering ram in fights over mates. Eocarcharia and its relatives were forerunners of Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis, a massive meat eater that dwarfed T. Rex in size.

Site: Saharan Desert, Niger

Age of specimen: 110 million years (Cretaceous)

Discovered: 2000

UChicago researchers: Paul Sereno and Stephen L. Brusatte, SB’06

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus

As Cretaceous carnivores go, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus is practically a household name. To paleontologists, it’s a semiaquatic predator, with nostrils placed to help it breathe in water, dense bones for buoyancy control, and a dorsal spine that turned its back into a sail. To the rest of us, Spinosaurus’s claim to fame is its size—nine feet longer than its nearest T. Rex competitor, it’s the largest known fossil of a carnivorous dinosaur. That distinction earned Spinosaurus a starring role in Jurassic Park III. Even the story of its discovery has a whiff of Hollywood about it. The first Spinosaurus fossil was unearthed by a German paleontologist in 1915, only to be destroyed in World War II. Nearly a century later, a new specimen was dug from the ground by a Moroccan fossil hunter and eventually made its way to Italy, where researchers worked to confirm its origin and authenticity.

Site: Kem Kem Beds, Morocco

Age of specimen: 95 million years (Cretaceous)

Discovered: 1915, 2013

UChicago researchers: Paul Sereno and former postdoctoral scholar Nizar Ibrahim

Updated 11.28.2017 to use paleontologist for all references to researchers in this field.