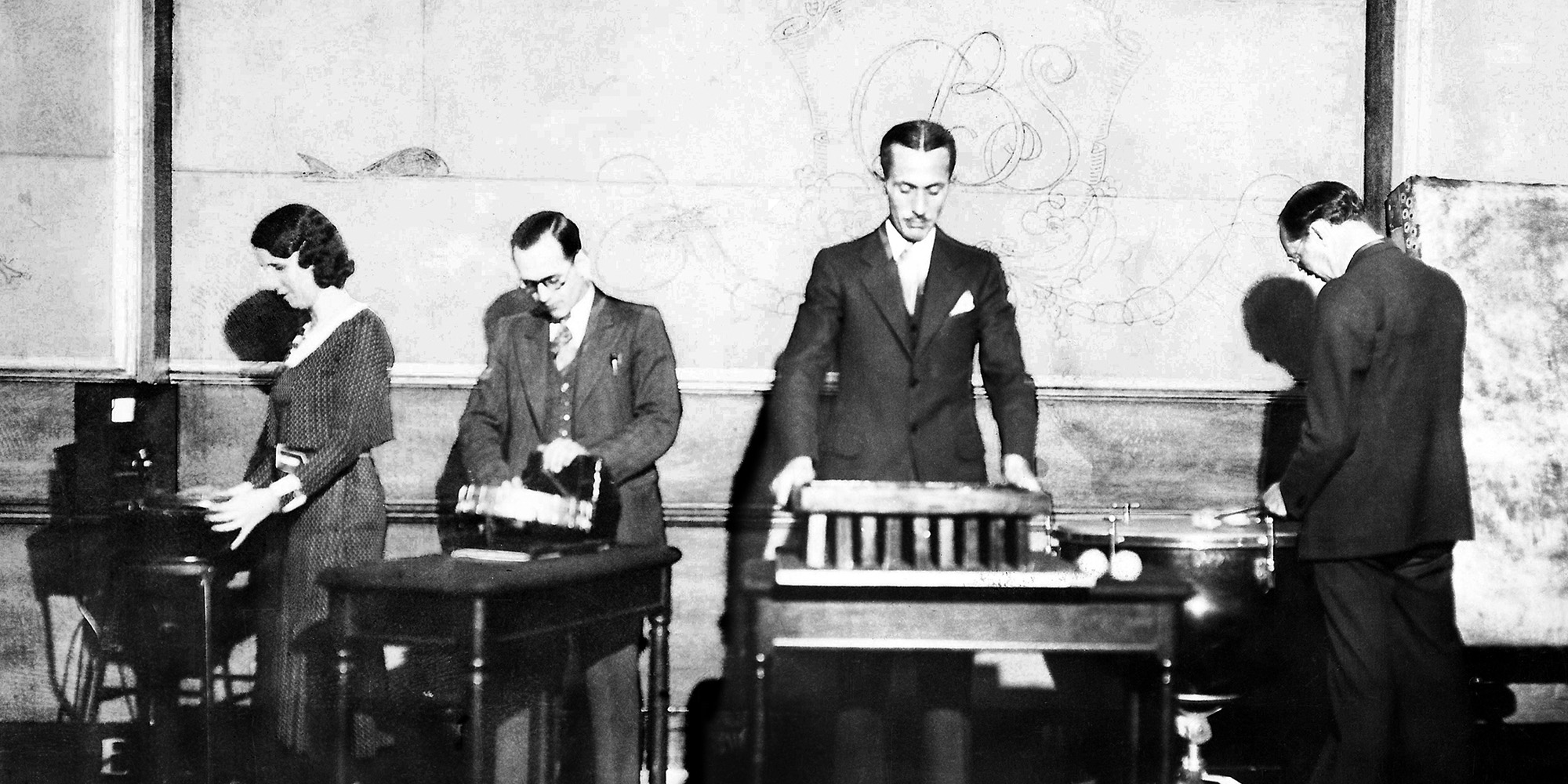

The CBS Radio sound effects team on The March of Time, circa 1931. (Culver Pictures Inc./Wikimedia Commons)

Two scholars in sound studies discuss golden age of radio dramatist Arch Oboler’s (EX’36) acoustic tricks.

Arch Oboler, EX’36, wrote drama, comedy, and polemics, but it was his “weird fiction”—speculative storytelling blending fantasy, science fiction, and horror—that made him famous during radio’s golden age. Best known for his work on the supernatural radio anthology Lights Out, Oboler was a technical innovator, experimenting with novel audio effects (see “If You Frighten Easily …”).

Two scholars in sound studies describe Oboler’s acoustic tricks and discuss how, as legendary horror actor Boris Karloff once said, “All sheerest horror is in sound.”

Initially sound effect innovators tried to make their tools of the trade match the actual sound, says Amy Skjerseth, a doctoral candidate in sound studies. For instance, studio spaces had areas with wooden flooring for indoor footsteps and trays of gravel for outdoor.

Eventually, instead of using spareribs for bone snapping, sound artists might use celery: “It sounds a lot more real than reality.” That visceral reaction is how sound artists, especially in horror, “get underneath people’s skin,” she says. Oboler followed suit, cutting cabbages in half with a cleaver and squishing wet noodles with a bathroom plunger. (Use your imagination for what images these edible audios were meant to conjure.)

Skjerseth’s previous research into the sounds of horror also focused on vocal work, in particular men’s and women’s voices. Neil Verma, AM’04, PhD’08—one of Skjerseth’s mentors—notes that in early radio, producers shied away from women actors working together; they worried the audience wouldn’t be able to tell them apart. (Oboler frequently wrote plays with multiple women protagonists, such as “Murder in the Script Department.”)

In modern horror, a common trope is the female scream, but Oboler often incorporated high-pitched male screams, which Skjerseth finds fascinating. There’s an artistry to screaming that has so much effect in horror, she says. “Screams were just different in radio drama than they are today,” partly due to equipment limitations and the nature of live broadcasts. Episodes might include prerecorded sound effects or music, but vocal performances were usually live.

In the radio studio, there was a danger that screams—or any loud vocals—might filter into another actor’s microphone and sound distorted, says Skjerseth. Microphones required calibration for screams, and mixing board operators had to be cognizant of the gain, so loud sounds didn’t overpower softer ones. Only one thing has ever struck terror into the heart of Frankenstein’s monster, said Boris Karloff—“the microphone in a broadcasting station.”