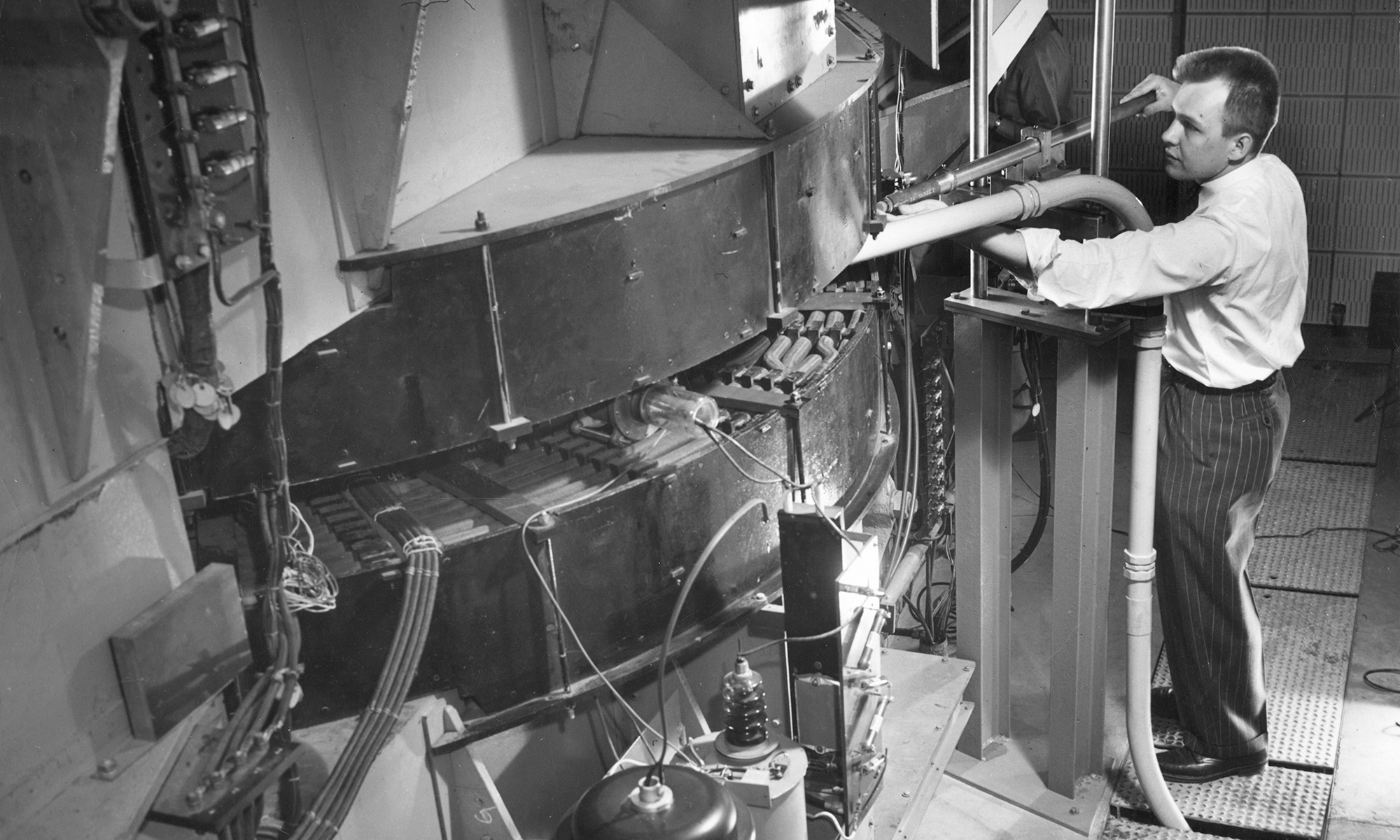

UChicago Photographic Archive, apf2-00056, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library

The Accelerator Building comes down this year. These are the machines it was built to house.

After World War II, the University of Chicago remade its atomic science program for peacetime to focus on the particles that make up the universe and on the use of radiation in cancer treatment. As comfortable as it must have been to work on a squash court under the stands of Stagg Field, the atomic researchers on campus needed their own space for this expanded mission. In the late 1940s the University broke ground on the Accelerator Building, a cancer research and treatment hospital, and a home for three new institutes—one for nuclear studies, one for the study of metals, and one for radiobiology and biophysics.

Located on the southwest corner of 56th and Ellis, the Accelerator Building was constructed from 1947 to 1949 to accommodate two new massive particle accelerators (or “atom smashers,” as they were popularly known at the time) as well as offices and facilities for medical research and treatment. At the end of this year, the Accelerator Building will be demolished to make way for a new engineering and science building that will meet the needs of today’s researchers in the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and the Chicago Quantum Exchange. Read on to learn about the machines that gave the Accelerator Building its name—and purpose.

Betatron

Chief betatron engineer Charles R. McKinney inserts a sample into the 100-MeV (million electron volt) collider (photograph above). Built in 1949 by General Electric, the betatron generated gamma rays (high-energy X-rays) and mesons (subatomic particles composed of a quark and antiquark). It was used to understand the forces holding the nucleus together and to study cosmic rays. The machine, which cost about half a million dollars to build, was put up for sale in 1959, as researchers turned their attention to experiments on different equipment—the University even offered to throw in 300 tons of concrete shielding. But in 1965, with no buyers coming forward, the decision was made to dismantle the betatron.

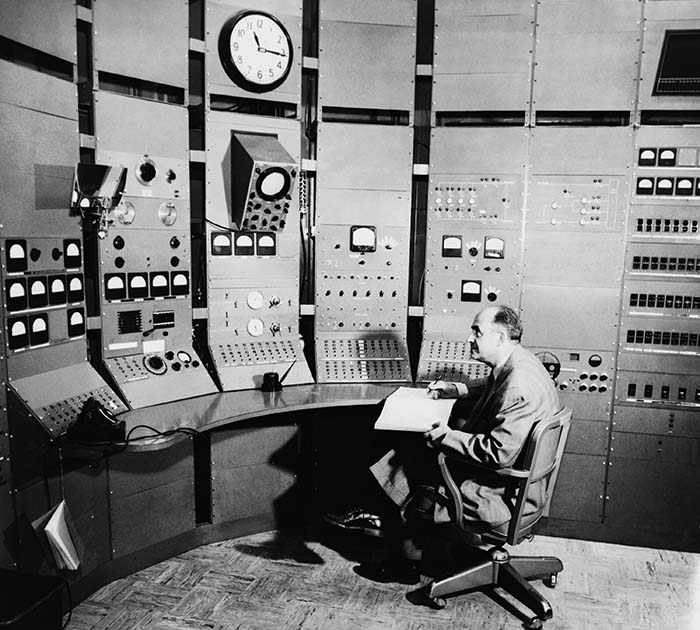

Synchrocyclotron

Enrico Fermi (left) chats with Herbert L. Anderson and John Marshall in front of the 170-inch, 450-MeV synchrocyclotron they designed. An improvement on Ernest Lawrence’s (EX’24) classical cyclotron, which uses a magnet to accelerate charged particles in a spiral until they escape in a high-energy beam, the synchrocyclotron has an electric field that varies as particles approach the speed of light. This machine wasn’t the University’s first cyclotron. The first, constructed in the late 1930s under the direction of William D. Harkins, the Andrew MacLeish Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, was housed in the Buildings and Grounds service building behind the old Press Building (today’s bookstore).

The synchrocyclotron was completed two years after the Accelerator Building. The heavyweight device’s 2,073-ton magnet yoke was brought to campus in sections—some weighing as much as 82 tons—and assembled on-site with the help of the building’s built-in crane. The synchrocyclotron was used to study the structure of the atom and in experiments on proton therapy for cancer treatment.

Fermi sits at the controls of the synchrocyclotron. After achieving the first controlled, self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in 1942, the 1938 Nobel laureate in physics shifted his focus to high-energy physics. He used the synchrocyclotron and the University’s other accelerators to study interactions between pions—or pi-mesons, the lightest mesons—and protons or neutrons. After a brief stint at Los Alamos from 1944 to the end of the war, Fermi returned to UChicago, serving as a professor of physics and a founding member of the Institute for Nuclear Studies (now the Enrico Fermi Institute) until his death in 1954.