1963 illustration of the main quadrangle by Mel Nickerson. (University of Chicago Magazine archives)

President Beadle and the secret campaign to beautify the campus.

George Beadle served as president of the University of Chicago from 1961 to 1968. His wife Muriel (1915–94), a journalist and civic organizer, published a number of books, including These Ruins Are Inhabited (1961), a study of life at Oxford University; The Fortnightly of Chicago: The City and Its Women 1873–1973 (1973); and The Cat: History, Biology, and Behavior (1977). She cowrote the book The Language of Life (1966) with her husband, a Nobel Prize–winning geneticist.

This is the third in a series of excerpts from her book Where Has All the Ivy Gone? A Memoir of University Life (University of Chicago Press, 1972).—Carrie Golus, AB’91, AM’93

From its first multipurpose building, Cobb Hall, the University grew rapidly. By the time it celebrated its first quarter-century, it had more than forty buildings, most of them Gothic. This mode was appropriate for the self-styled Oxford of the West; in fact, the University’s Hutchinson Commons is a replica of Christ Church Hall, and the tower on an adjacent building is a squashed-down version of the one on Magdalen College.

Taken individually, these early University of Chicago buildings are nothing to get excited about, but as massed around the central Quadrangles of the campus they are stunning in effect. This austere “gray city” is set among broad lawns studded with massive oaks and elms and is that rarity on the urban scene: a place of cloistered serenity (visually, at least) that lies within a hundred yards of busy city streets.

In 1961, this effect was best appreciated at a distance. When one saw the buildings at close hand, it was apparent that they had had little maintenance in recent years. (And no wonder: the University had invested $29,000,000 in the urban renewal effort, money that had come out of both the instructional and the housekeeping budget.) George couldn’t stand the shabbiness of the place, and he urged the business manager to spend some money on maintenance.

“An institution as great as this one ought to be able to keep its brass polished,” he said.

There were so many other things that the University’s scant funds could be spent on—things of more obvious utility—that the refurbishing program began tentatively and without fanfare. Surprisingly, there was no backlash. In fact, a professor here and there commented on how nice it was to see fresh varnish on the beautiful old oak doors or to lecture in a classroom whose cracked walls had been patched and repainted.

Thus encouraged, George attacked an eyesore that in his opinion was even worse than the state of the buildings. He is an enthusiastic gardener, and the condition of the grassy areas shocked him. The weedy lawns, scarred with brown spots or patches of raw dirt, had the weathered look of a city tomcat who is still alive only because he has become tough enough to beat the odds.

The beginning of the campaign was modest. All George attempted was to replant and nurture the grass on a circular island about fifty feet in diameter which had been created by the pattern of the driveway leading from University Avenue into the great central Quadrangle.

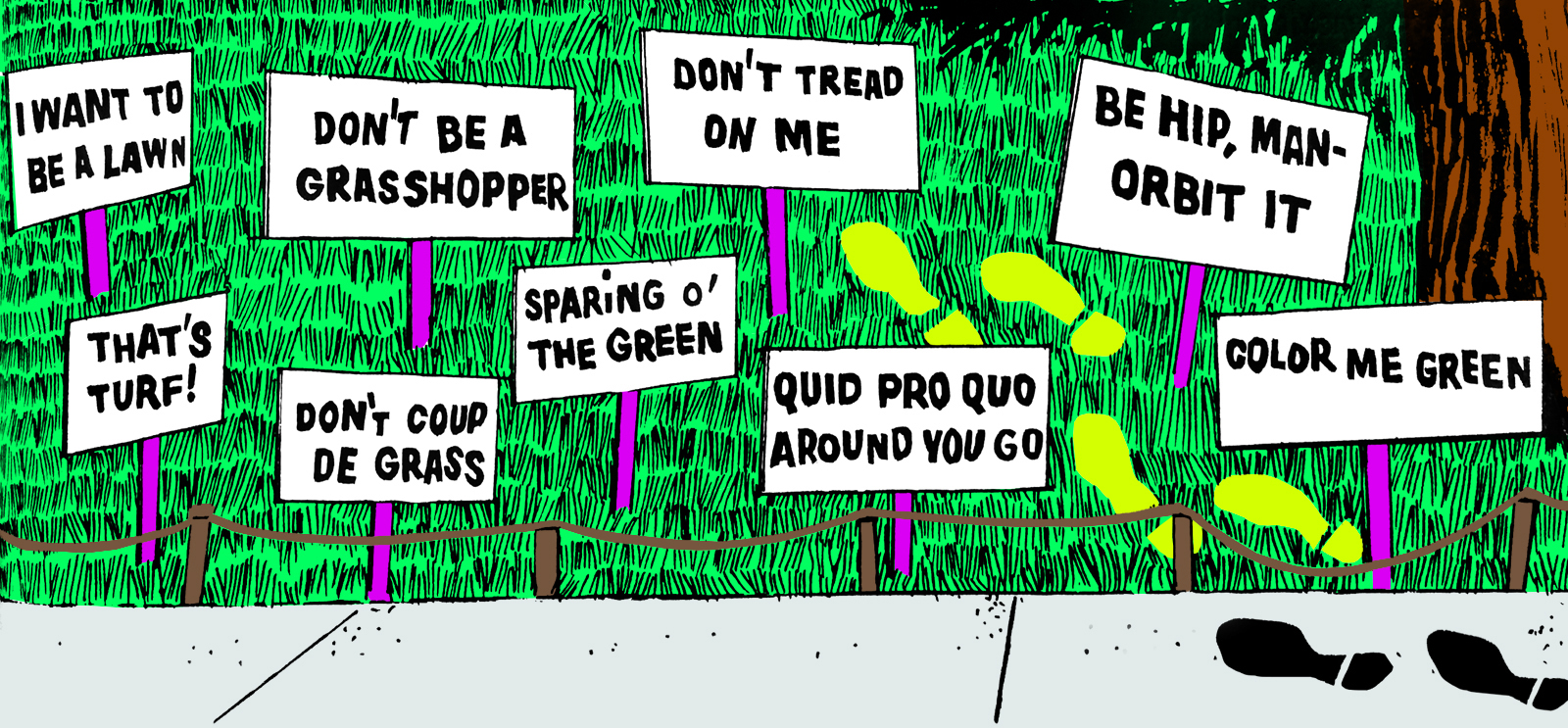

The replanting was easy. The nurturing was not. People habitually crossed the circle every which way, and when the first tender shoots of grass came up in late October, they got mashed down by scores of scurrying or scuffling feet. “Please Don’t Walk on the Grass” signs were ignored. Visual barriers of clotheslines between low posts were deliberately breached.

“You’d think we were trying to interfere with their academic freedom,” George snapped one night when he arrived home after passing the usual scene of devastation.

We went out to dinner that night, a rare kind of dinner date because it had no purpose other than personal pleasure. Our host was Edward Maser [AM'48, PhD'57], new chairman of the Art Department, who had come that year from the University of Kansas. The guests of honor were Dr. and Mrs. Franklin D. Murphy; he had been the chancellor at Kansas and was now newly appointed to the same position at UCLA. Inge Maser is a spectacularly good cook, and after dinner George was sufficiently relaxed (especially in the company of another university president) to vent his ire and to voice his perplexity about “the grass problem.”

I don’t remember which member of the company was the strategist and which was the tactician, but two brilliant minds—lubricated by brandy—came up with this pair of ideas:

“The main thing you have to do is to persuade people to walk around the circle instead of across it.”

“And the way to do it is to post signs they’ll want to read. Same principle as the Burma Shave signs.”

“For example?” George asked.

“Well, certainly not ‘Keep Off the Grass,’” Frank Murphy replied. “How do you like ‘Don’t Tread on Me’?”

And then the rest of us were off.

“How about ‘That’s Turf’?”

“Or ‘Color Me Green’?”

“What’s that line from Gertrude Stein? ‘Pigeons in the grass, alas’? How about ‘Where Is the Grass, Alas? You Are Not a Pigeon.’”

“Or ‘Be a Nonconformist—Stay Off the Grass.’”

“On the Grass, Nyet! Off the Grass, Si!”

“Ho! Let’s form a Green International!”

“Good. The Green Front Against Oppression of Grass.”

“That’s not scholarly enough for the University of Chicago. It ought to be a Committee of some sort.” That was Ed Maser speaking. He had been a Chicago undergraduate during the Hutchins-encouraged rise of interdisciplinary Committees, and was well aware of the University’s passion for them.

So, naturally, we named our new organization the Committee on Grass, Interdisciplinary and International. That final word was added in order to make the title more impressive, but it turned out to be accurate. When the first signs began to appear on campus and even the New York Times [“New Front Group Rife at Chicago U.: Green International Seeks Grass Roots Influence,” November 26, 1961] took note of the new “front group” at the University of Chicago, slogans came in from all over the United States and from Canada, as well as from people in many scholarly disciplines at the University itself.

We charter members of the Committee on Grass decided at the organizational (and only) meeting that anyone who submitted a usable slogan would become a Lifetime Member, Entitled to All the Privileges Thereunto Appertaining. He would receive a membership card, printed in green ink, and a button for a suit lapel, reading GRASS ROOTS. These were subsequently dispensed by a lady who lived in the President’s House but was identified only as The Secretary and was reachable only through a box number at Faculty Exchange (the University’s campus mail service).

Another decision made by the charter members was that no sign, however exotic, would be explained.

“If they’re at the University of Chicago, they’re bright enough to figure it out,” Ed Maser declared.

Hence the contribution from a member of the Oriental Institute staff was most welcome; it said a little something about grass but was written in Assyrian cuneiform as of the eighth century B.C. A graduate in the humanities provided “Ou sont les tapis d’autrefois?” The wife of a visiting professor of Swedish advised walkers to “Gaa uternom, Peer Gynt!” Seneca was heard from, via Classics, but in translation: “Shame may restrain what the law does not prohibit”; and someone in the Music Department set down the opening bars of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring.

Reporters for the student newspaper nearly went crazy trying to find out for sure who was behind all this calculated nonsense. But inasmuch as no student ever arose as early as 5:30 A.M., when the signs were posted by a gentleman who lived in the President’s House, the anonymity of the Committee on Grass was preserved.

The campaign used up material as fast as a weekly comedy hour on TV, but it was worth the effort. People decided that they would indeed “Be Hip, Man—Orbit It!” (That was the contribution of the chairman of the Geophysics Department, who had teenage children.) The infant grass slumbered through the winter virtually inviolate.

An edited excerpt from Where Has All the Ivy Gone? A Memoir of University Life, by arrangement with Redmond James Barnett. ©1972, the University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.