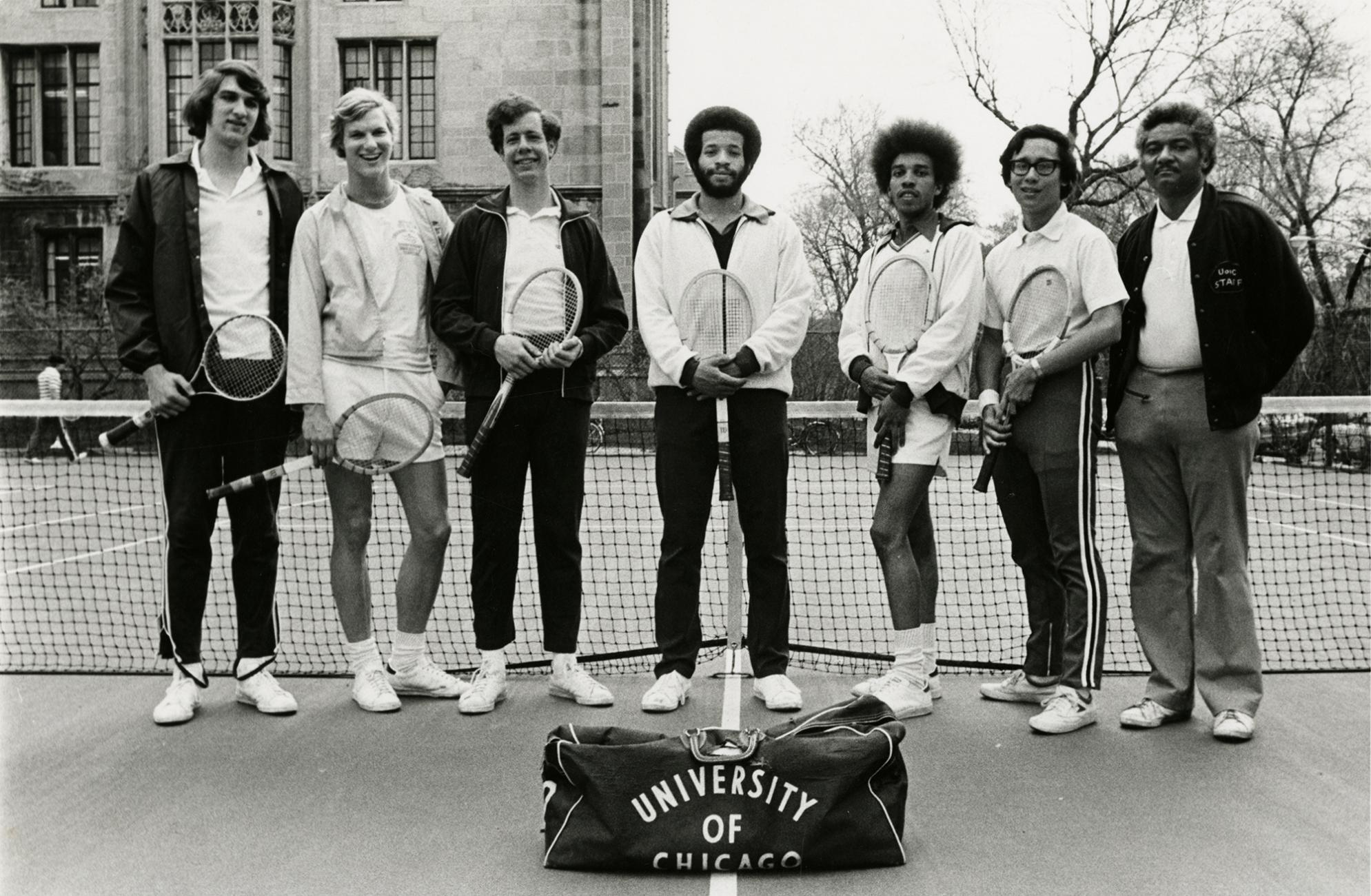

The University of Chicago tennis team in 1975. From left: Daniel Hayes, AB’78, MBA’79; Robert Smartt, AB’76; Terence Lichtor, AB’75, PhD’80, MD’80; Kim Williams, AB’75, MD’79; Wayne Threatt, AB’75; Kenneth Kohl, AB’79; and Coach Chris Scott. (UChicago Photographic Archive, apf5-03736, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library)

A coach’s lessons went well beyond tennis.

Some called him “St. Christopher.” My nickname for him is one I never shared with him—or anyone else—until now: “Chris Scott scientia; vita excolatur.” I used to say that to myself jokingly, but if we go back 50 years, it’s clear that Christopher Scott and my University of Chicago experience were so intertwined that it makes perfect sense.

It started in the summer of 1970, before my senior year of high school, when, along with about 60 other inner-city kids, I participated in the Office of Special Programs’ NCAA-sponsored tennis camp at Stagg Field. It was the initial year of that program, and the director, Larry Hawkins, had recruited Chris Scott to teach tennis. After finding out that he was the U of C’s varsity tennis coach, I approached him during a break and asked what it would take to become a student at the University. I told him that I had always wanted to attend but had been warned by my high school guidance counselor not to apply because the University of Chicago did not take kids like me from the Chicago Public Schools system. As an honor student, I had been told, I might be able to get in at University of Illinois Circle Campus.

Chris paused the tennis class for a few minutes, walked across the street to a pay phone, came back, and told me that after class I should go to an address on Woodlawn Avenue. It turned out that, without any hint, preparation, or warning, he had arranged for me to have a college interview at my dream school.

Fast-forward 16 months, and I was a 16-year-old UChicago freshman trying out for Chris’s varsity tennis team, thinking I was a tennis player because I had won a few high school matches. Chris was very clear about one thing—there was no way I was going to make that team with my experience. But if I worked really hard, maybe I would make the team as a junior, after the “big four” (Allen Friedman, AB’73; Jonathan Rosenblum, AB’73; Dan Rosenhouse, AB’73; and Alex Terras, EX’73) had graduated.

I thought I could prove myself to Chris by winning the intramural tournament for my dorm, Upper Rickert. But I lost in the first round, 6–0, 6–0 to another freshman, Terence Lichtor, AB’75, PhD’80, MD’80. Terry went on to win the tournament and was slotted for number five singles behind those four upperclassmen. My response was to study the sport and to practice as much as I could, sometimes for six hours on a given day. By spring I had challenged my way up to number seven, but in college tennis only six players are in the starting lineup.

In the first varsity match of the spring, I played as a sub at sixth singles, but the next day I beat our number six player, Dean Krone, AB’74, JD’85, in a challenge match. That put me in the inner circle—the starting lineup—and Chris began to mentor me more intently. He challenged everything about my game, both mechanically and mentally. I remember asking team captain Alex Terras, after a particularly difficult practice, why Chris was so tough on me. Nothing I did was ever good enough, it seemed. I was singled out for every little mistake or unforced error. I never forgot Alex’s answer: “Don’t you realize he’s given up on the rest of us? You’re the only one who has a chance!”

After that varsity season, Chris introduced me to the African American tennis scene in Chicago. The Chicago Prairie Tennis Club, one of the oldest US tennis organizations, sponsored me to play Chicago District Tennis Association (CDTA) tournaments in the 18-and-under category. I lost all eight tournaments in the first round. But after a full year of “the life of the mind,” recognizing that I could learn more than a bit from losing, I stayed at each tournament to watch the top seeds play. I gathered information about stroke mechanics, tactics, and strategy.

That fall I came back to the University of Chicago, and I never lost a challenge match for the rest of my college career. As I was now the number one singles player, Chris was able to secure my invitation for the CDTA’s 18-and-under Super Excellence program, where I could play with ranked players. With his demanding mentorship, in a tough athletic environment, I excelled. I qualified for the NCAA in both my junior and senior years and achieved high rankings in both the US Tennis Association and its African American counterpart, the American Tennis Association (ATA). More important, I gained life lessons and developed problem-solving and strategic-thinking skills—including a high level of frustration tolerance—that became the underpinnings of my medical career.

Throughout this time, Chris was pushing me for more and better. My best year of tennis came after my first year of medical school, when I achieved the number one national ranking in the ATA. Chris had by then served as my coach, mentor, professional doubles partner, and surrogate father. He tried to convince me to defer my second year of medical school and play on the professional tennis circuit. It was fortunate, in retrospect, that a back injury at a qualification tournament for the 1976 US Open derailed my professional tennis aspirations. I continued my medical training and settled for local and regional prize money to help defray educational expenses.

After medical school, I trained in internal medicine at Emory University, and I got to see Chris play in the 1979 ATA national tournament in Atlanta. He didn’t look good. He appeared short of breath and lost to a less-skilled player. It turned out that this was the first manifestation of his severe multivessel coronary heart disease and congestive heart failure. He underwent bypass surgery but never recovered enough to play competitively.

After I returned to the University of Chicago to complete cardiology training, he came to me for advice. I referred him to a senior colleague since I’m not a fan of treating family members, which he essentially was. But we had extensive conversations about nutrition, eating habits, and their effects on health. It was just a few years later that I received the fateful call from the emergency room at Chicago Osteopathic Hospital: Chris had sustained a cardiac arrest on the tennis court and could not be resuscitated.

Chris never got to see the full effects of his mentorship and how he essentially created a pathway through a simple phone call and constant badgering—more accurately, inspiration—for a socioeconomically deprived inner-city kid from the South Side of Chicago. He inspired me to become a medical school professor, one of a very few African American chiefs of cardiology or medicine department chairs, a scientist, a clinician, an educator, a health policy advocate, and a guideline author, now internationally known for promoting the field of cardionutrition in order to prevent premature cardiac events. Like his.

Kim Allan Williams, AB’75, MD’79, is the current chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine and editor in chief of the International Journal of Disease Reversal and Prevention. He served as president of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology from 2004 to 2005, board chair of the Association of Black Cardiologists from 2008 to 2010, and president of the American College of Cardiology from 2015 to 2016.