Bagpipers start the 2023 Folk Festival in Mandel Hall. (Photography by Jason Smith)

How the University of Chicago Folk Festival built its own tradition.

Every University of Chicago Folk Festival begins with bagpipes. What better way to inaugurate a weekend of traditional music—from a Cajun band to Mexican son huasteco to Bulgarian gadulka and back again—than the University’s own musical tradition? For many of us, our time on campus was bookended by the instrument’s droning wail.

Bagpipes are among only a few common denominators of the Folk Festival’s programming over its 63 years. That’s by design. The Folklore Society (the registered student organization that has always run the festival) typically considers any generationally transmitted music fair game. In other words, authentic folk music—not the contemporary genre of the same name that’s usually associated with acoustic instrumentals and singer-songwriters.

Beyond that, how, exactly, the festival defines “traditional music” is hotly debated among Folklore Society members. Every Wednesday night, both students and older community members—affectionately called “geezers”—huddle in a closet-sized meeting room in the basement of Ida Noyes Hall to discuss exactly that.

“There’s a lot of disagreement, even amongst our alumni members. But it’s always a fun challenge to draw an epistemology of what the Folk Fest is,” says Folklore Society copresident Jack Cramer, Class of 2023, a fourth-year music and philosophy major.

To understand the Folk Festival’s traditionalist platform, one must understand the context of the first festival in 1961 and, before it, of the Folklore Society, founded in 1953. Still before that, during the New Deal, commercially available folk song recordings—produced by folklorists like John and Alan Lomax and distributed by labels such as Folkways Records—introduced hyper-regional musical traditions to broader audiences.

What began as preservation initiatives kicked off a full-blown movement. Musicians like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Muddy Waters, Lead Belly, and Burl Ives became cult figures, and urban areas created spaces for performing and hearing those folk traditions. The Gate of Horn, the very first venue in the United States devoted solely to folk music, opened in Chicago in 1956; Old Town School of Folk Music followed less than a year later.

A Folk Festival glossary

wingding (n.) (′wi ŋ-′diŋ) A communal performance of folk music, in which attendees are invited to play their instruments and/or sing.

hootenanny (n.) (′hü-tə-′na-nē) A variety performance in which participants play for an audience.

geezer (n.) (′gē-zər) A non-undergraduate member of the Folklore Society. Not derogatory.

The folk movement’s most eager adherents were young people—particularly urban, highly educated, middle- and upper-class White people. Jaded by the postwar industrial boom, many in this cohort latched onto folk music as a symbol of a halcyon, anticonsumerist past. College towns and campuses became hubs for folk music, creating a so-called coffeehouse circuit for performers.

Hyde Park was no exception. Hootenannies sprouted up on and off campus, and the Fret Shop, a guitar store that rotated through a few locations in Hyde Park in the 1960s, was a popular haunt for anyone who wanted to show off their chops or learn a lick or two. By 1960 the University of Chicago Folklore Society was the campus’s largest student organization, coordinating sprawling jam sessions and occasional concerts featuring luminaries like Odetta, Bob Gibson, Peggy Seeger, and the New Lost City Ramblers. Starkey Duncan Jr., PhD’65, a professor in the psychology department, served as the Folklore Society’s longtime faculty adviser.

However, as folk music itself commodified, hardline folkies advocated for a narrower definition that judged musicians on yardsticks of “authenticity.” Among those hardliners was 1960–61 Folklore Society president Mike Fleischer, LAB’52, EX’63. Enrolling in school after a stint in the Navy, where he was a disc jockey, Fleischer was several years older than his peers and had little patience for pop culture, telling the Chicago Tribune in a festival preview feature that he’d “[thrown] a shoe at his own TV screen eight months ago and doesn’t intend to have it fixed.” Fleischer also opined that he wasn’t interested in making the UChicago Folk Festival “a commercial showcase for folk singers working a night club bill, … [as] so-called folk festivals in other cities have turned into”—a thinly veiled jab at the Newport Folk Festival.

With the counsel of Old Town School of Folk Music cofounder Dawn Greening, Fleischer became a crucial conduit to the lively folk scene in Greenwich Village and cemented the UChicago Folk Festival’s relationship with the New Lost City Ramblers, who would headline the first festival and many thereafter.

Fleischer “was gregarious, almost hyper—he had a very active mind,” recalls David Gedalecia, EX’64. “He always wanted to get something done.”

The first Folk Festival’s commitment to authenticity also inspired its basic format, still in place today: performances in Mandel Hall by night, workshops in Ida Noyes by day. At the workshops attendees come face-to-face with musicians, learning tunes and technical tricks of the trade on their own instruments. The only meaningful changes to this formula are that the festival is now two days long instead of three and that it has been live streamed for the past three years thanks to a gift from D. Garth Taylor, AM’73, PhD’78, founder of the School of American Music in Three Oaks, Michigan.

The collegiality animating the Folk Fest was not only a reaction to commercial mega festivals like Newport but also truer to the spirit of many folk traditions themselves. “These students just wanted to learn more about life outside of the lives they knew, and spend a weekend with the artists,” says journalist Mark Guarino, whose book Country and Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival was published by the University of Chicago Press in April.

In part, the festival’s format—combining performances with intimate opportunities to learn from and even jam with artists—was a response to the extractive, often impersonal nature of the same albums that kindled the folk revival. Some of the artists documented on those folk anthologies—almost always rural and/or working class—never heard from labels again after putting out recordings. Many artists only learned they had a massive following through their invitation to the festival.

“The artists were known by these students but forgotten by the people who had recorded them,” Guarino says. When multi-instrumentalist Bill Monroe performed at the 1963 festival, he had “thought no one really cared about him, but suddenly, he was surrounded by all these young people who really liked him.” Country blues singer and guitarist Mississippi John Hurt “was living in poverty in the Jim Crow South, but he performed in … all these places and got to enjoy the last couple of years of his life before he died. A lot of artists’ lives were made better by that festival.”

Because of the musicians’ relative obscurity, locating desired headliners wasn’t always easy. In preparation for chairing the third annual Folk Festival, Bob Kass, AB’62, pored over Folkways anthologies and handpicked artists he thought deserved a solo spotlight. In the summer of 1962, he dropped off blues guitarist Elvin Bishop, EX’64, at home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, before continuing on to small towns in the South to find folk singers Almeda Riddle and Mississippi Fred McDowell. The next hurdle was convincing them to perform.

Riddle “was afraid to come as a woman, alone, to Chicago, but she agreed to come if [fellow Arkansas folk musician] Jimmie Driftwood would also be there,” Kass recalls. “And when [I visited Fred McDowell], you know, this was 1962 Mississippi. He was definitely nervous. He didn’t invite me into his house.”

The integrationist ideals undergirding the folk revival took on heightened significance in Hyde Park, then in the throes of urban renewal. In collaboration with the University, the federal government had redeveloped racially integrated Hyde Park and other neighborhoods on the South Side, clearing out tenement housing. The redevelopment functionally displaced many of Hyde Park’s Black residents and razed some commercial strips, including a building once occupied by the Fret Shop.

“The South Side was a very thriving place before urban renewal. It was like a big, nice, Southern city—a lot of Black-owned businesses and hundreds of blues clubs,” Bishop says.

Already hooked on the blues as a teenager in Oklahoma, he’d listed Northwestern University and the University of Chicago as his first-choice schools. He ended up at the latter, enrolling in the College on a National Merit Scholarship. Campus was just within reach of Chicago’s greatest blues clubs. Working off recommendations from campus cafeteria workers, he saw Muddy Waters and his band—James Cotton, Otis Spann, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, and Pat Hare—his first week in Chicago.

That week Bishop also met someone who would change the trajectory of his life: Paul Butterfield, LAB’60. Butterfield and his circle—including guitarist Nick Gravenites, EX’60; keyboardist Mark Naftalin, AB’64 (Class of 1965); folk superfan and lifelong Hyde Parker Nina Helstein, LAB’60, AB’64, AM’75, PhD’95; and guitarist Mike Bloomfield (not a student or a Hyde Parker, but part of the neighborhood’s musical milieu)—were among the few young White people game to explore the South Side’s blues clubs. At places like Pepper’s (43rd and Vincennes) and Theresa’s (48th and Indiana) they saw Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy, and others. Butterfield, Bishop, Gravenites, and Naftalin took what they’d heard and played at campus “twist parties,” attended by students and young South Siders.

Likewise, the UChicago Folk Festival has showcased various strains of the blues—a folk tradition itself integral to Chicago—since its inception. Post-1960s festival planners made more conspicuous efforts to expand beyond American folk, though that remains the festival’s bread and butter. Most years you can count on catching bluegrass, old-time, and Cajun acts, the last of these thanks to connections with longtime festival supporters.

The first festival appearance by a Cajun group coincided with a miraculous chapter in Folk Festival history. The seventh annual festival had the misfortune of falling a day after the 1967 Chicago blizzard, which dumped nearly two feet of snow on the region in a single evening. The city completely shut down—but not the Folk Festival. The then president of the Folklore Society, Mark Greenberg, AB’67, AM’70, convened an emergency meeting the next morning to discuss whether to call off the festival, which was slated to begin that night. They agreed to move forward.

With some creative thinking and a whole lot of dumb luck, the festival went off with a shuffled schedule and only a few substitutions. Buddy Guy and his band made their way on foot to Hyde Park to play a Friday night set. The next day, bluegrass duo Flatt and Scruggs managed to get to Mandel Hall after negotiating a special landing at Meigs Field, the only airfield open in the city. (Scruggs, it turns out, was a licensed pilot.)

And Greenberg says a troupe including the great Cajun fiddler Dewey Balfa—whose daughter Christine headlined the 2023 festival with her band—made it there by sheer force of will, driving from Mamou, Louisiana, “straight through that damn storm.” By the time the weekend was over, a folklorist panel was the sole event that had to be canceled outright.

“It was the only thing happening. For a weekend, we had a monopoly on entertainment in Chicago,” Greenberg remembers.

COVID-19 was the other force majeure that interrupted the Folk Festival’s normal proceedings, but the festival wasn’t canceled; it went virtual in 2021 and piloted a hybrid format in 2022. Helstein says any fears about the efficacy of a virtual festival were dispelled when she saw the artists perform. “Because it was online, artists could perform all over the world, in the regions where their music came from,” Helstein says. “It was incredibly special.”

That made the in-person 2023 Folk Festival something of a homecoming. Society copresidents Cramer and Nick Rommel, Class of 2024, a third-year history major, were not only helming the proceedings but also attending their first in-person fest since matriculating at UChicago. “You spend months planning an event you have only a nebulous concept of,” says Eli Haber, AB’22, copresident of the society during both years affected by COVID. “But that’s what has kept people putting on this event for 60-plus years.”

After COVID restrictions lifted on campus, Cramer and Rommel say, student attendance at both society meetings and Ida Noyes contra dances spiked to levels unseen in more than a decade. “I think a lot of people in the years below us are really, really hungry for RSO involvement. They’re excited to get out and do things,” Cramer explains.

Geezers have taken notice too. In recent years, Helstein says she has counted attendees from her perch in the upper level of Mandel Hall. To her delight, at the 2023 fest she found it easier to count the number of empty seats.

“We called the time of the first festival the folk revival. So maybe that makes this the folk revival revival,” she says.

For those who lived through those early festivals, though, the folk revival never really ended. Helstein is the longest-running attendee and volunteer in Folk Festival history. Kass lives in Hyde Park too, having retired from the Laboratory Schools in 2015. Before his death in 2004, Mike Fleischer had gone on to work as an executive at Flying Fish and Folk Era Records, two influential Chicagoland folk music labels. Mark Greenberg works in folk music as a musician, educator, writer, and media producer based in Montpelier, Vermont. And if you’re lucky, you can catch Elvin Bishop, Mark Naftalin, and Nick Gravenites doing what they do best, albeit usually on stages closer to home: Naftalin in Westport, Connecticut, and Bishop and Gravenites in the San Francisco Bay Area.

As for today’s Folklore Society? After each year’s festival, members take just one week off to congratulate themselves on a job well done. The next Wednesday, they’re back at it again, imagining the timeless sounds next year’s festival might bring.

Hannah Edgar, AB’18, is a Chicago-based freelance writer.

The Bob Dylan mystery

If you know anything about the University of Chicago Folk Festival, you’ve likely heard lore about its most famous headliner-who-wasn’t: Bob Dylan.

Eyewitnesses agree on some key details, many of which are recounted in Country and Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival (University of Chicago Press, 2023), Mark Guarino’s recent folk history. Dylan certainly passed through Hyde Park in the weeks leading up to the first Folk Festival, materializing at jams in the New Dorm (later Woodward Court) and the Fret Shop. At the time, Dylan was a round-faced 19-year-old still introducing himself as Bobby Zimmerman. Biographers place his visit in late December 1960, following up on an invitation from Kevin Krown, EX’64, a student in the College he’d met that summer in Denver.

Sources also agree on another awkward detail: the Dylan they knew was musically forgettable. Late history professor Moishe Postone remembered him as “just a bad Woody Guthrie imitator.” Nina Helstein, LAB’60, AB’64, AM’75, PhD’95, more or less agrees. “He wasn’t Bob Dylan then. He was a guy that came by and played a lot of Woody Guthrie music.”

Associate professor of music Steven Rings, whose book Sounding Bob Dylan: Music in the Imperfect Tense is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press, says those contemporary accounts square with Dylan’s then-consuming Guthrie obsession and with the various backstories he fabricated while playing the Greenwich Village circuit in the early 1960s. There and in Chicago, he took on the moniker “Bob Dylan” and claimed he was the son of New Mexican cattle ranchers.

If Dylan’s goal was to impress folk sophisticates in college towns, he didn’t always succeed. Paul Levy, AB’63, remembers Dylan playing for a student committee affiliated with the Folk Festival, likely vying for a spotlight in the Sunday afternoon hootenanny featuring “local Chicago folksingers.” Levy cast the deciding vote not to invite Dylan to play.

“It must have been that he showed up hungry and homeless. … I had the impression he was a completely lost soul,” Levy remembers. As a consolation prize, Levy and his roommate agreed to let Dylan sleep in the cupboard of their 53rd Street apartment for a few days.

“There’s no question he was already super ambitious. I think a lot of the folk revivalists were turned off by that,” Rings says. “In Minneapolis, the Dinkytown folk purists had a lot of contempt for him … like, ‘Oh, this guy, you know, he thinks that he’s the first one who’s ever heard Woody Guthrie.’”

It’s unclear exactly how long Dylan was in Hyde Park. He arrived in New York City either on or by January 24, 1961. Krown and Mark Eastman, AB’62, joined him there, though whether they traveled there together or separately is, like most things Dylan related, unclear.

What also remains foggy is whether Dylan wheeled back to Chicago to attend the Folk Festival as a spectator in February, as some attest he did—including second-ever festival chair Mike Michaels, EX’61, who shared his encounters with Dylan in a 2012 University of Chicago Magazine essay. David Gedalecia, EX’64, corroborated Michaels’s recollections. He remembers playing the February 3 reception in Ida Noyes with Michaels when he noticed someone “bobbing and bouncing” to the music.

“He listened to us for, I don’t know, 45 minutes or more. I said [to Mike], ‘Who was that guy?’ and he says, ‘Bob Dylan. He does a lot of Guthrie songs, plays guitar, writes some of his own songs.’ And I said something like, ‘Oh, that’s cool,’ and we kept playing. It didn’t make any impression,” Gedalecia recalls.

But Rings thinks it’s a stretch that Dylan backtracked to Chicago to attend the first Folk Festival so soon after arriving in New York. “Dylan’s life has been picked over, and picked over, and picked over. It’s surprising to me that there wouldn’t be any record of that. Every car ride this guy took is documented.”

That said, no surviving documents or bookings irrefutably place Dylan in New York that weekend either. The earliest recording of him there can be sourced to undated living room performances in New Jersey, possibly made at Krown’s urging in February or March 1961.

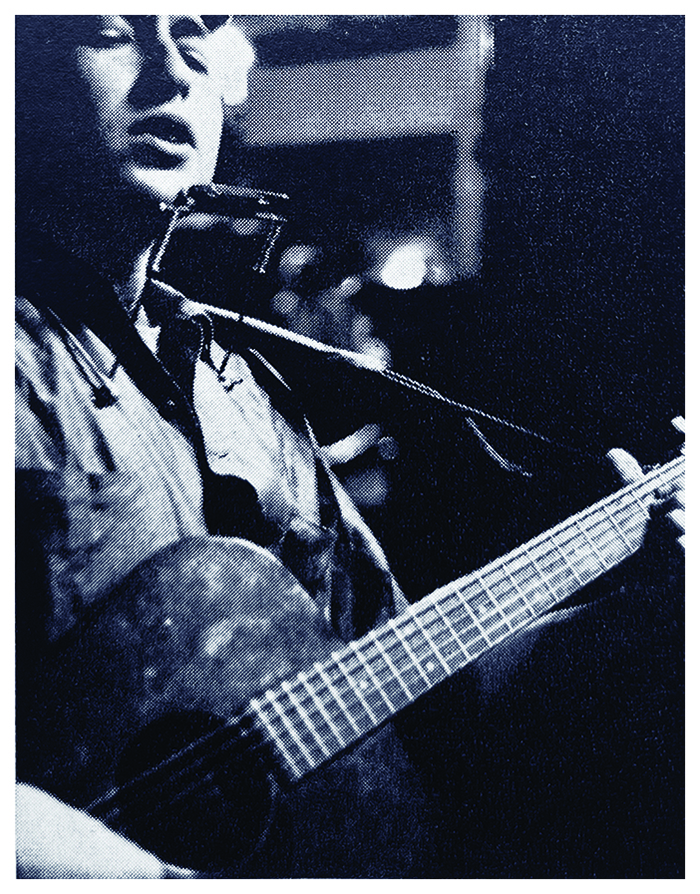

The Magazine does have a tantalizing clue of its own, previously unacknowledged by Dylan biographers: a close-up of a harmonica- and guitar-slinging youngster who’s a dead ringer for little Bobby Zimmerman, apparently snapped during a student wingding at the first Folk Festival. Rings believes the photo “absolutely” depicts Dylan, an identification further corroborated by Levy and Gedalecia.

Dylan, ever elusive, offers no clarification himself. His only memoir, Chronicles: Volume One (Simon and Schuster, 2004), simply says he drove to New York in a four-door sedan, tearing “straight out of Chicago—clearing the hell out of there.” Given Dylan’s own track record with biographical accuracy, we’ll likely never know the truth. (And no, Dylan did not respond to our requests for comment.)

Updated 05.25.2023 to acknowledge that Mark Guarino’s book Country and Midwestern: Chicago in the History of Country Music and the Folk Revival (University of Chicago Press, 2023) recounts many of the details about the first Folk Festival and Bob Dylan’s possible presence at the event.

Updated 08.07.2023 to clarify the Mike Fleischer’s (LAB’52, EX’63) role at Flying Fish and Folk Era Records.