The first Folk Festival’s basic format is still in place today: performances in Mandel Hall by night, workshops in Ida Noyes by day. (All photography by Jason Smith)

A writer's diary.

This writer attended their first-ever Folk Festival in 2023. Here’s how the 12 hours of musicking played out on the festival's second day, Saturday, February 11.

10:30 a.m.

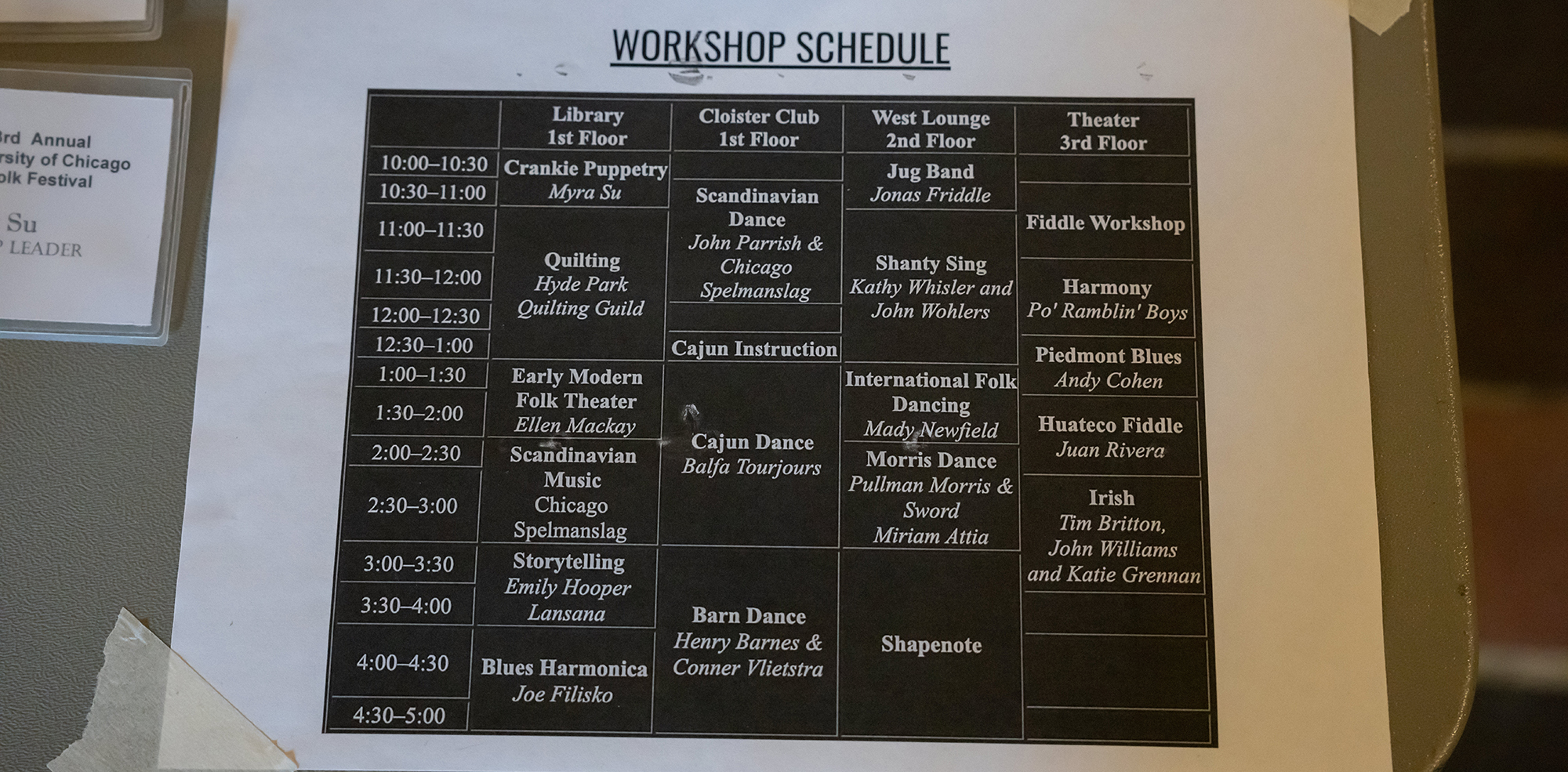

Violin strapped on my back, I arrive at the Ida Noyes third-floor theater in time for the fiddle panel, a festival stalwart. The idea is for bow-toting headliners to compare and contrast their various styles in an approachable, conversational setting. Unfortunately, owing to a miscommunication (ah, student-run festivals!), we're down five of five fiddlers. Quick thinking by volunteers Jules Vance, AB’22, and Lena Birkholz, Class of 2025, gets us in a round robin learning songs from one another. Birkholz teaches us the “Ballydesmond Polka No. 1,” a traditional Irish tune.

Eventually, old-time fiddler Henry Barnes, guitarist Conner Vlietstra, and violinist Juan Rivera shuffle in. They chat with one another, take audience questions, then jam with Vance, who handily alternates between guitar and violin. The workshop goes long; I don’t get the sense anyone minds, myself very much included.

1:30 p.m.

After a lunch break, it’s back to the same space for a primer on son huasteco, led by Rivera. Vance, who’s played mariachi for 16 years, moderates—but, as the two violinists stress, the two Mexican-born genres couldn’t be more different. Son huasteco originated in northeastern Mexico and uses a tight trio of violin, huapanguera (eight-string bass guitar), and jarana (five-string rhythm guitar). All three musicians sing, their voices often floating into buttery falsete.

Ironically, Rivera was born and raised in mariachi territory, on a farm outside Guadalajara. He didn’t learn son huasteco until he moved to Mexico City, where the expansive country’s folk styles intermingle.

The workshop ends with Rivera demonstrating ornamental finger patterns typical to son huasteco. The violinists in the audience play back in an exuberant call-and-response.

3:00 p.m.

Down the stairs and across the way, Hyde Park's own Sacred Harp singing group packs the west lounge wall-to-wall with singers of all stripes—including people who, a few moments before, would not have described themselves as “singers.” (I am in this camp.)

“If you were told you weren’t needed at mandatory chorus practice, and that you can’t sing your way out of a paper bag, don’t let that stop you!” a member encourages us. “We’re singing for each other. It’s not a performance.”

The group specializes in shape note singing, a simplified form of musical notation which has become associated with its own unique performance practice and repertoire since its ascendance in 19th-century America. The notes appear in their expected places on musical staves, but the shapes of the note heads—triangles, ovals, squares, diamonds—help singers find the correct scale degree. It also uses a unique solfège system that starts with fa and doesn't use do, re, or ti at all. (In a diatonic context, mi functions as ti, the leading tone, instead.) Singers are encouraged to keep time themselves by waving a free hand in a simple up-down beat, as did several of Saturday’s attendees.

I sat in the tenor section, the best fit for my voice type but an auspicious decision for another reason: tenors usually have the melody in shape note singing. By the end of the first hour, even the most timorous tenors in my section were happily bellowing along.

7:30–11:00 p.m.

After a dinner break, it’s time for the second night of performances in Mandel Hall. Opening tonight is Barnes and Vlietstra, the Ohio River Valley–based fiddle and guitar duo from that morning's panel-that-wasn’t; they also played the Friday night show. Barnes and Vlietstra make a funny pair: Vlietstra is a man of few words, smiling placidly and gently swaying as his fingers work overtime on the guitar. Barnes, on the other hand, is loquacious and cerebral. (Case in point: During Saturday's show, he demonstrated the artificial intelligence–generated licks he's worked into his sets over the past couple of years.)

The festival’s second night is more or less a promenade of other time-honored festival favorites, old-time included: Irish traditional, classic bluegrass, acoustic blues, and Louisiana Cajun. But within those usual suspects are a whole lot of surprises. I’m completely entranced with the sound of uilleann pipes (played virtuosically by Tim Britton), a woodsier, more flexible cousin to the bagpipes. Jerron Paxton, who also performed at the 2015 festival, is a multi-instrumental renaissance man, pirouetting from a blues song name-checking Kankakee, Illinois, to a stride piano number quoting Beethoven's “Moonlight” Sonata at its head.

In a refreshing callback to past Folk Festivals, the headliners also play with one another. Paxton calls Vlietstra back to the stage for a banjo-guitar cover of “Maple Leaf Rag,” because “that guy can do more things with a guitar than a monkey can with a coconut.” Later, Paxton's the guest of honor, stepping in to play rhythm bones alongside Cajun band Balfa Toujours.

Not for a moment does the audience forget that students are the wizards behind this magical evening. Throughout the night, Folklore Society members and festival volunteers paired off to dance in the wings and at the periphery of the stage. (“Just like old times,” said Nina Helstein, LAB’60, AB’64, AM’75, PhD’95, when I mentioned this to her later.) Folklore Society copresidents Jack Cramer, Class of 2023, and Nick Rommel, Class of 2024, told dad jokes in the dead space between sets—yet another Folk Festival tradition.

But it's no joke when Cramer says his final farewell from the stage. A first-year during the pandemic shutdown, Cramer had never attended a live festival; he'll graduate in a few short months. His voice breaks with tears as he formally closes that year's festivities.

That must feel like its own convocation, bagpipes and all.