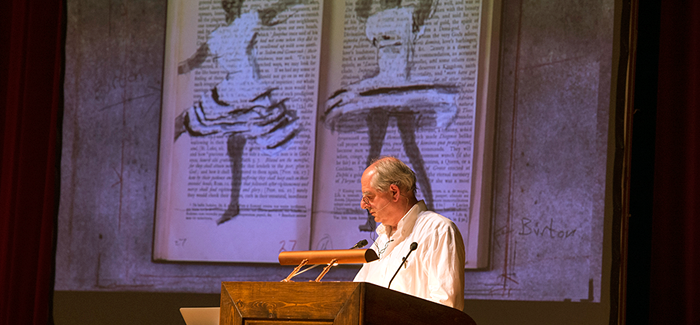

Accompanying sounds, Kentridge says, shape how we process images. (Photography by Robert Kozloff)

The Neubauer Collegium sets sail with two talks and a visit by artist William Kentridge.

The University’s new think tank, the Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society, has an ambitious agenda: to help scholars pursue big questions “across boundaries of method, discipline, and genre, as well as institution and nation.” Named for benefactors Joseph Neubauer, MBA’65, and Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer, the joint venture of the humanities and social sciences divisions celebrated its public launch in early October with a lecture by South African artist William Kentridge. Versatile and political, Kentridge is known globally for his animated films based on drawings and collage. He also makes prints and sculpture and has designed works of opera and theater mixing music, live acting, animation, and puppetry.

The title of his talk, “Listening to the Image,” signaled Kentridge’s—and the collegium’s—omnivorous approach. Kentridge told the capacity crowd in Mandel Hall that he’s wrestling with a big question of his own: how can an artist create meaning, and move viewers, by combining image and sound?

To suggest answers he marshaled a laptop, a Steinway piano, and two able assistants from Chicago’s Lyric Opera. Genial and portly at the podium, Kentridge first projected a drawing of a tree and listed the thoughts he’d had while making it. He next showed a video pairing the turning pages of a Larousse dictionary with audio from a 1932 political rally, to illustrate his experiments combining “found” sound and constructed images.

Our brains process images differently when the accompanying sound changes. As proof, Kentridge invited tenor John Irvin and pianist Craig Terry to sing and play while he projected a series of animated drawings that depicted a baldish white-shirted man—a stand-in for the artist—pursuing a baldish black woman who danced across the turning pages of a book.

Kentridge played the images three times with different soundtracks. While Irvin crooned Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s “The Song Is You,” the bald man’s pursuit of the lovely dancer felt poignant and hopeful. But when Terry raced through the frenetic piano rag “Dizzy Fingers,” the same scenes seemed farcical and doomed. For the artist, this proves “the extraordinary promiscuity of images—how they will sleep with so many different types of sound.”

To help uncover what he calls “the grammar of sound and image,” Kentridge asked the audience to be “guinea pigs” for a project he’s preparing for the 2014 Vienna Festival. As Irvin sang a melancholy tune from Franz Schubert’s Winterreise song cycle, once again the baldish man chased the dancer. This time, however, Kentridge added a haunting political coda to the animation: spare red lines grew into a tree on a barren landscape; more red lines descended from branches and morphed into lynched bodies that dropped to the ground. The piece ended by zooming out from a vast ledger, perhaps a list of people jailed or disappeared under South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Kentridge wants to connect Johannesburg with Vienna—that is, to link art and politics “in the colonies,” as he calls them, to thinkers, consumers, and even oppressors in centers of power. The day after his lecture in Mandel Hall, he joined South African writer and curator Jane Taylor for a public panel on how studio collaborations—and the unfettered mixing of artistic traditions and media—can create a more powerful impact than individual efforts. Such practices, he says, have “the virtues of bastardy,” a concept Kentridge explored with anthropologist Rosalind Morris, PhD’94, in That Which Is Not Drawn (Seagull Books, 2013).

As an example Kentridge played clips from Ubu and the Truth Commission, a 1997 play Taylor wrote and he directed with the Handspring Puppet Company. A mash-up of live theater, music, animation, puppetry, and witness testimony from the postapartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the work originated by chance. In 1996 Kentridge had teamed up with a choreographer to produce a piece for the 100th anniversary of Alfred Jarry’s absurdist play Ubu Roi. Separately he was creating a puppet play using documentary evidence from the Truth Commission. There was not enough time to finish both, he recalls, “So the only way out was to smash the two together and hope for the best.”

This and other improvisations convinced Kentridge that often “the half-formed, very vague ideas that I had were better than the certainties that were presented.” As a director he decided to “make a safe space for indecision, for uncertainty, for doubt” to grow.

Historian David Nirenberg, who moderated the discussion, hopes a similar sense of adventure will animate the research projects launched under his watch as the Neubauer Collegium’s Roman Family director. In its first year, the collegium will fund 18 cross-disciplinary teams working on topics from game design to early writing systems to the impacts of human industrial activity.

Drawing faculty from 17 humanities and social sciences departments, the teams also include scholars from divinity, law, business, and medicine. More visiting fellows will arrive in Chicago from around the world to further shake things up. Talking with Kentridge, Taylor reminded the crowd why that was a good idea. “The point of a collaboration is not to do what you know how to do,” she said. “It’s to do something that you never imagined doing before.”