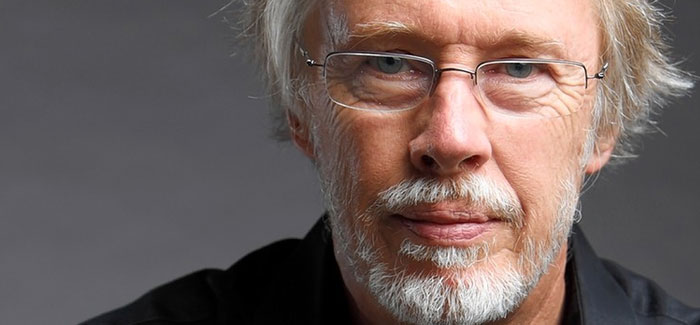

Charles Baxter. (Photography ©2014 Keri Pickett)

Class in session with Charles Baxter.

Although Charles Baxter was at the Seminary Co-op to promote his latest collection of short stories, There’s Something I Want You to Do: Stories (Pantheon), he read from it sparingly, pointing out that we were perfectly capable of doing it ourselves. After all, his 11 books of fiction and essays notwithstanding, Baxter is first and foremost a teacher: at the University of Minnesota and Warren Wilson College, and previously at the University of Michigan. As UChicago creative writing faculty member Rachel DeWoskin pointed out, Baxter was also a regular visitor to the English classes her mother taught at Ann Arbor’s Community High School when he was at Michigan.

So why waste time on in-class reading? Instead, telling the story of how Something came to be, Baxter presented a master class on inspiration, process, and the turns the imagination can take.

So why waste time on in-class reading? Instead, telling the story of how Something came to be, Baxter presented a master class on inspiration, process, and the turns the imagination can take.

Baxter was in a self-described “dry spell” when he took out a 35-year-old typewritten draft of an unfinished story. The story was about a woman in the throes of postpartum depression who leaves her husband and baby, told from the point of view of the husband. Baxter started a new story with the same characters, set years later, when the baby is a 17-year-old boy. He called it “Bravery” and proceeded to write stories centered around five virtues—loyalty, bravery, chastity, charity, and forbearance—and five vices—lust, sloth, avarice, gluttony, and vanity.

While working on the collection, Baxter did a reading at Penn State University-Erie. As he described the concept, a student named Kyle Kerr asked him if the characters from the virtue stories would recur in the vice stories. Baxter, who hadn’t thought of that idea, followed the suggestion and thanked Kerr in the book’s acknowledgments.

His longest reading of the night was a deleted scene from the story “Chastity;” he joked that we were getting “the director’s cut.” He explained that the scene—in which a woman demands that her adult son stop procrastinating, find a wife, and have children, all while she does yoga with a cigarette in her mouth—was too funny for the rather somber story, and its “novel-like” pace was too slow and expansive for the required compression of a short story.

He had more to say: about the autobiographical nature of morality and his widely quoted contention that “irony is the new chastity,” because it reflects “the refusal to open oneself.” The crowd of about 40 hung on every word, as though listening to a particularly gripping story.