An illustration from the 1533 account of the execution of a witch charged with burning the German town of Schiltach in 1531. (Illustration by Briefmaler, {{PD-1923}})

Centuries ago, falling temperatures across Europe spelled danger for suspected witches.

Five hundred years ago, falling temperatures may have contributed to the waves of witchcraft trials that swept Europe. A 2004 study on the correlation between cold weather and witch trials by Chicago Booth economist Emily Oster, then a Harvard PhD student, resurfaced this year in a number of news articles. Oster, who studies economics related to health and the developing world, speculates that perhaps the past year’s “extreme weather events” played a part in renewed interest in her witch-trial research. According to the study, the economic effects of a long cold snap, along with cultural beliefs in the supernatural, made presumed witches easy scapegoats.

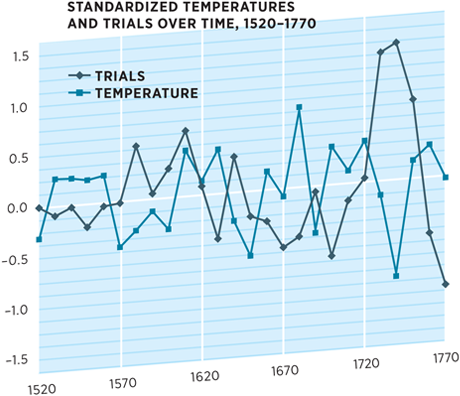

Oster collected weather and trial data from 1520 to 1770, when temperatures dropped to about two degrees Fahrenheit lower than previous centuries. During this period, crops failed, fish stopped migrating, and witchcraft trials rose across Europe. Most of the continent’s one million witch executions took place during these centuries.

Oster drew the data from 11 European regions, including parts of modern-day France, Great Britain, and Switzerland. Graphing the temperature and number of trials (standardized for each region and averaged over the 11 regions) against time, Oster found a strong inverse correlation between number of trials and the temperature. The period immediately following 1720, which witnessed the most trials and the lowest temperatures, offers the most extreme case.

Studies of witchcraft trials tend to focus on populations’ psychological factors. But “key underlying motivations,” Oster’s paper reminds us, “can be closely related to economic circumstances.”