(University of Chicago)

Steve Cicala, AB’04, takes the time to honor his unlikely but generous mentor Gary Becker.

Different constraints are decisive for different situations, but the most fundamental constraint is limited time.—Gary Becker, Nobel Lecture, December 9, 1992

I was not an economist when I met Gary Becker, AM’53, PhD’55. I was a 20-year-old undergraduate at the University of Chicago with quite simply no idea what I was going to do after graduation. The University was holding a conference to honor Milton Friedman’s (AM’33) 90th birthday, and Gary was giving the keynote speech at a Quadrangle Club dinner for invited guests. I was not one of them.

I hadn’t spent my childhood reading Capitalism and Freedom, and economics was not the family business. The prior summer I had been reading Whitman, Thoreau, and Emerson and working in a restaurant to stem the tide of student loans I was accumulating. I was interested in economics because I was at the University of Chicago, after all, and it’d be a shame to leave without some exposure. I volunteered at the conference that day and, curious to see the keynote dinner speech, asked if I could attend.

As Nobel laureates, central bankers, Council of Economic Advisers chairs, and other distinguished guests made their way to assigned tables throughout the dining room, I was told a seat for me had been found, but I would have to be on my best behavior. Ronald Coase couldn’t make it to the dinner, and there was an open seat at the head table. It was Gary; Guity Becker, PhD’73; Milton; Rose Friedman, PhB’32; Jim Heckman; Lynne Heckman, AM’73; University President Don Randel and his wife, Carol; trustee Ned Jannotta; and me—a philosophy/political science/economics undergraduate who wasn’t even supposed to be in the room.

I sat next to Guity, who when I approached the open seat said, “You know, there’s supposed to be a Nobel laureate sitting here, so I hope you can keep up your end of the conversation.” I must have done all right, because she encouraged Gary when I asked him if he had any research positions available. He told me to come by his office and we’d figure something out—which I promptly chalked up to bar talk, and left for three months to study Western European civilization in Barcelona. It’s a testament to how much Gary trusted Guity’s judgment that there was a position waiting for me when I returned.

In our research meetings, not being an economist gave me the freedom to ask the kinds of questions that a graduate student already sold on the discipline would be embarrassed to ask: Why assume rationality? How do we express morality in this framework? Would you like to read Plato with me? I had the idea that there was more economics to the Republic than is commonly acknowledged and wanted to work through it with him. He not only agreed—he recruited Dick Posner to join us for a quarter-long reading course that turned into my undergraduate thesis.

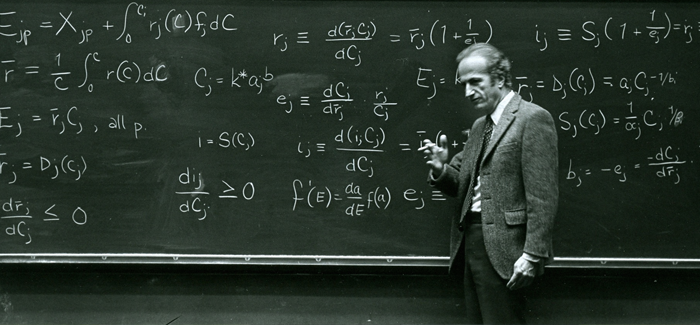

I enrolled in Gary’s Human Capital graduate class, after he suggested that it “shouldn’t be too hard,” and followed up with Price Theory in the fall. “Is economics an art or a science?” Gary would ask after a particularly difficult problem set. “Both,” he would answer his own question, to the great relief of a lecture hall full of students terrified that they were about to be called on. The science part is widely taught—equilibrium borne from optimization to test falsifiable hypotheses. The art of economics is much tougher, as any student who has received zero points for a 20-page problem set write-up will attest.

Gary emphasized the craftsmanship of building a model—identifying the essential elements of a problem and casting them in a framework that would yield valuable insight once the science was applied. His recognition of this critical artistic element led to a sort of humility that is not often associated with the Chicago school’s emphasis on the science of economics. When answering one of his own questions in class, he would invariably begin with, “Well, it depends …”

Gary is most widely credited with “extending the domain” of economics, but I think this is like saying that Galileo simply made a nice telescope. Before Gary, there was a method for analyzing markets and other methods for analyzing various forms of human behavior—as if the former were not entirely contained within the latter. This made economists vulnerable to the belief that markets were something greater than a mechanism to mediate human interactions. It was acceptable (or even admirable) to have faith in free markets, rather than understanding them.

Yet the “invisible hand” is a metaphor for an empirical proposition, not doctrine and certainly not magic. More than simply extending economics, Gary’s work tests this proposition by demonstrating the validity of the economic approach at its most basic level: human behavior. The proof is by contradiction: suppose decisions to marry, have children, go to school, commit crimes, etc., are all totally unresponsive to incentives and the economic approach utterly fails to explain how people behave in these contexts. Why would one put any stock in our ability to understand markets? Is there too little competition for spouses? Are the stakes too low when facing time in prison? Of course not.

Most economists have come around to the importance of his work as contributions to sociology, demography, criminology, etc. But even more fundamental is that it serves as a lever to elevate the whole of economics above Ptolemaic theories that match observed phenomena without actually understanding the underlying mechanisms.

After graduating from the College, I spent a couple of years as an RA at Gary’s eponymous center, a few doors down from his office at Booth. He had long since transformed economics and received every possible accolade, yet at 75 he was still teaching a full course load, running two seminars, and coming in to work on Sundays. He would usually stop by on his way out, and we’d catch up. We’d talk about that week’s applications workshop paper, what we were working on, his daughter’s latest movie, his grandson’s latest feat of technology, and life in general (“no girls until you finish!”). When the time came to decide on a graduate program, Gary told me how important his time at Columbia University was for establishing his independence: “You can’t come back if you’ve never left.”

Of the many things I learned from Gary, a single powerful lesson stands out: the value of revealed preference in judging one’s actions. Declared priorities are easily betrayed by actual behavior. I bring up this intuition because it’s what makes telling this story more about him than me. No one had a more profound understanding of the scarcity of time than Gary, and yet he spent his own with extraordinary generosity.

Gary took me on as an undergraduate with no skills to speak of, gave me time that I surely did not deserve, and set the course that I have been on ever since. I believe those actions reveal more about his character than any formal praise I could offer.

Steve Cicala, AB’04, is an assistant professor at the University’s Harris School of Public Policy and a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research.