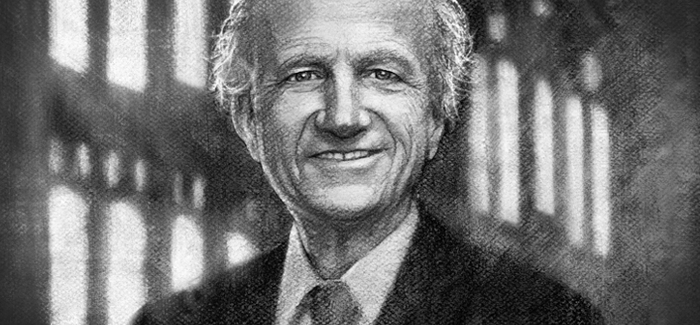

(Illustration by Allan Burch)

Reflections on the life and work of trailblazing economist Gary Becker.

Economist Gary Becker, AM’53, PhD’55, never retired. Actively contributing to the field he helped redefine—teaching, researching, speaking, blogging—until his death in May at age 83, Becker was such a profound influence that he had long received the sort of extravagant tributes that typically precede the presentation of a gold watch.

In 2001 Milton Friedman, AM’33, described his former student, colleague, and fellow Nobel laureate as “the greatest social scientist who has lived and worked in the last half century.” Friedman’s use of “social scientist” rather than “economist” illustrated Becker’s transformational role. Perhaps nobody did more to make the terms synonymous.

His early work, including research on the economic impact of discrimination and the rational basis of criminal behavior, won him few admirers and little attention. Such border crossings into territory reserved for sociologists and psychologists were not yet commonplace in economics.

Becker, continuing on the path he charted for himself, made it so. He received the 1992 Nobel Memorial Prize in recognition of his “radical extension of the applicability of economic theory in his analysis of relations among individuals outside of the market system.”

As former US Treasury secretary Lawrence H. Summers put it, Becker turned economists’ attention to “the stuff of human life.” In addition to discrimination and crime, he studied subjects such as education, marriage, and family, which were once deemed beyond the reach of the dismal science. “Becker fused the cool logic of economic reason with a fiery imagination,” Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, PhD’92, wrote in his New Republic remembrance, “a combination that enabled him to use economics to enlighten wide swaths of human behavior.”

Becker’s death, from complications after ulcer surgery, inspired a wide swath of praise from those who were touched by his life and work. Selections are collected below. (For more on Becker’s influence, see “A Theory of the Allocation of a Nobelist’s Time.”)

Steven Levitt

William B. Ogden Distinguished Service Professor in Economics

Gary had a reputation for being extremely tough. He absolutely terrified people. But not once in twenty years did I hear him raise his voice, or even appear openly angry. People feared him because he could see the truth. At his core, though, he had a deep humanity.

Years ago, my son Andrew died unexpectedly in the middle of the school term. I cancelled my classes for a few weeks. Only when I returned did I discover that Gary had stepped in, without anyone asking him to, and had taught the classes in my absence. The only problem was that my students were so disappointed when I returned!

Lawrence H. Summers

Former US Treasury Secretary

Before Becker, economics was about topics like business cycles, inflation, trade, monopoly and investment. Today it is also about racial discrimination, schooling, fertility, marriage and divorce, addiction, charity, political influence—the stuff of human life. If, as some assert, economics is an imperial social science, Gary Becker was its emperor.

Robert J. Zimmer

President of the University of Chicago

He was intellectually fearless. As a scholar and as a person, he represented the best of what the University of Chicago aspires to be.

Kevin M. Murphy, PhD’86

George J. Stigler Distinguished Service Professor of Economics

He was devoted to and helped define Chicago economics, a rich tradition that uses economics to understand and shape the world around us. Gary was an inspiration to several generations of Chicago students—instilling in them the love for economics that he lived and breathed.

The Economist

Becker’s trailblazing earned plenty of criticism. The interdisciplinary adventurism it embodied peeved other social scientists, who doubted that cool-headed analysis played much part in matters of love or larceny. But his work yielded unexpected insights and forced social scientists to rethink their assumptions and sharpen their analyses, the better to learn why people behave as they do and how policy can best help. Whole branches of microeconomics owe their existence to him. It is hard to imagine a more welfare-improving contribution.

Edward Lazear

Former Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers

Gary Becker was a giant who used his genius to make sense of issues that had formerly resisted analysis. He integrated economics into more general social science and won over his critics. He demonstrated that analytic thinking and economic analysis were the social scientist’s most powerful tools.

Ilya Somin

Professor of Law at George Mason University School of Law

Sadly, I never got the chance to meet Prof. Becker. But I did exchange e-mails with him about a mutual research interest several years ago. I was skeptical that a Nobel Prize winner would bother responding to a request from an obscure assistant professor in another field. But he sent a very informative reply within a few hours after I e-mailed him. I have heard that this was just a typical example of his generosity.

Richard Griffin

Director of the UK’s Institute of Vocational Learning and Workforce Research

When he first wrote Human Capital he was accused of debasing learning. Surely learning is good in itself regardless of its economic outcome? I have some sympathy with that view, but I have more sympathy with the view that education, including workplace learning and development, delivers tangible benefits: better wages, better services, better care, better job satisfaction, services, wellbeing and better profits. This is almost taken for granted now. Becker is a big part of the reason it is and we should be grateful for that.

Peter Klein

Associate Professor of Applied Social Sciences and Director of the McQuinn Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership at the University of Missouri

A friend of mine was at Chicago in the 1990s when Becker was in his mid-60s and already a Nobel laureate. Like most economists in the department, my friend went to the office and worked Saturdays and Sundays. Becker was usually the first to arrive and the last to leave. “He’s not only the smartest person here,” I was told, “but the hardest worker!”

Richard A. Posner

US Court of Appeals Judge and Senior Lecturer at the Law School

In memoriam: Gary S. Becker, 1930–2014. The Becker-Posner blog is terminated.