In the early 1960s there was no comprehensive civil rights bill and Jim Crow segregation was still widespread in parts of the nation, particularly in the Deep South. With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill there was considerable optimism that racial progress would ensue and that the principle of equality of individual rights (namely, that candidates for positions stratified in terms of prestige, power, or other social criteria ought to be judged solely on individual merit and therefore should not be discriminated against on the basis of racial origin) would be upheld.

In the early 1960s there was no comprehensive civil rights bill and Jim Crow segregation was still widespread in parts of the nation, particularly in the Deep South. With the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill there was considerable optimism that racial progress would ensue and that the principle of equality of individual rights (namely, that candidates for positions stratified in terms of prestige, power, or other social criteria ought to be judged solely on individual merit and therefore should not be discriminated against on the basis of racial origin) would be upheld.

Programs based solely on this principle are inadequate, however, to deal with the complex problems of race in America because they are not designed to address the substantive inequality that exists at the time discrimination is eliminated. In other words, long periods of racial oppression can result in a system of inequality that may persist for indefinite periods of time even after racial barriers are removed. This is because the most disadvantaged members of racial minority groups, who suffer the cumulative effects of both race and class subjugation (including those effects passed on from generation to generation), are disproportionately represented among the segment of the general population that has been denied the resources to compete effectively in a free and open market.

On the other hand, the competitive resources developed by the advantaged minority members—resources that flow directly from the family stability, schooling, income, and peer groups that their parents have been able to provide-result in their benefiting disproportionately from policies that promote the rights of minority individuals by removing artificial barriers to valued positions.

Nevertheless, since 1970, government policy has tended to focus on formal programs designed and created both to prevent discrimination and to ensure that minorities are sufficiently represented in certain positions. This has resulted in a shift from the simple formal investigation and adjudication of complaints of racial discrimination to government-mandated affirmative action programs to increase minority representation in public programs, employment, and education.

However, if minority members from the most advantaged families profit disproportionately from policies based on the principle of equality of individual opportunity, they also reap disproportionate benefits from policies of affirmative action based solely on their group membership. This is because advantaged minority members are likely to be disproportionately represented among those of their racial group most qualified for valued positions, such as college admissions, higher paying jobs, and promotions. Thus, if policies of preferential treatment for such positions are developed in terms of racial group membership rather than the real disadvantages suffered by individuals, then these policies will further improve the opportunities of the advantaged without necessarily addressing the problems of the truly disadvantaged such as the ghetto underclass. The problems of the truly disadvantaged may require nonracial solutions such as full employment, balanced economic growth, and manpower training and education (tied to—not isolated from—these two economic conditions).

By 1980 this argument was not widely recognized or truly appreciated. Therefore, because the government not only adopted and implemented anti-bias legislation to promote minority individual rights, but also mandated and enforced affirmative action and related programs to enhance minority group rights, many thoughtful American citizens, including supporters of civil rights, were puzzled by recent social developments in black communities. Despite the passage of civil rights legislation and the creation of affirmative action programs, they sensed that conditions were deteriorating instead of improving for a significant segment of the black American population. This perception had emerged because of the continuous flow of pessimistic reports concerning the sharp rise in black joblessness, the precipitous drop in the black-white family income ratio, the steady increase in the percentage of blacks on the welfare rolls, and the extraordinary growth in the number of female-headed families. This perception was strengthened by the almost uniform cry among black leaders that not only had conditions worsened, but that white Americans had forsaken the cause of blacks as well.

Meanwhile, the liberal architects of the War on Poverty became puzzled when Great Society programs failed to reduce poverty in America and when they could find few satisfactory explanations for the sharp rise in inner-city social dislocations during the 1970s. However, just as advocates for minority rights have been slow to comprehend that many of the current problems of race, particularly those that plague the minority poor, derived from the broader processes of societal organization and therefore may have no direct or indirect connection with race, so too have the architects of the War on Poverty failed to emphasize the relationship between poverty and the broader processes of American economic organization. Accordingly, given the most comprehensive civil rights and antipoverty programs in America’s history, the liberals of the civil rights movement and the Great Society became demoralized when inner-city poverty proved to be more intractable than they realized and when they could not satisfactorily explain such events as the unprecedented rise in inner-city joblessness and the remarkable growth in the number of female-headed households. This demoralization cleared the path for conservative analysts to fundamentally shift the focus away from changing the environments of the minority poor to changing their values and behavior.

However, and to repeat, many of the problems of the ghetto underclass are related to the broader problems of societal organization, including economic organization. For example, as pointed out earlier, regional differences in changes in the “male marriageable pool index” signify the importance of industrial shifts in the Northeast and Midwest. Related research clearly demonstrated the declining labor-market opportunities in the older central cities. Indeed, blacks tend to be concentrated in areas where the number and characteristics of jobs have been most significantly altered by shifts in the location of production activity and from manufacturing to services. Since an overwhelming majority of inner-city blacks lack the qualifications for the high-skilled segment of the service sector such as information processing, finance, and real estate, they tend to be concentrated in the low-skilled segment, which features unstable employment, restricted opportunities, and low wages.

It is not enough simply to recognize the need to relate many of the woes of truly disadvantaged blacks to the problems of societal organization; it is also important to describe the problems of the ghetto underclass candidly and openly so that they can be fully explained and appropriate policy programs can be devised. It has been problematic, therefore, that liberal journalists, social scientists, policymakers, and civil-rights leaders were reluctant throughout the decade of the 1970s to discuss inner-city social pathologies. Often, analysts of such issues as violent crime or teenage pregnancy deliberately make no references to race at all, unless perhaps to emphasize the deleterious consequences of racial discrimination or the institutionalized inequality of American society. Some scholars, in an effort to avoid the appearance of “blaming the victim” or to protect their work from charges of racism, simply ignore patterns of behavior that might be construed as stigmatizing to particular racial minorities.

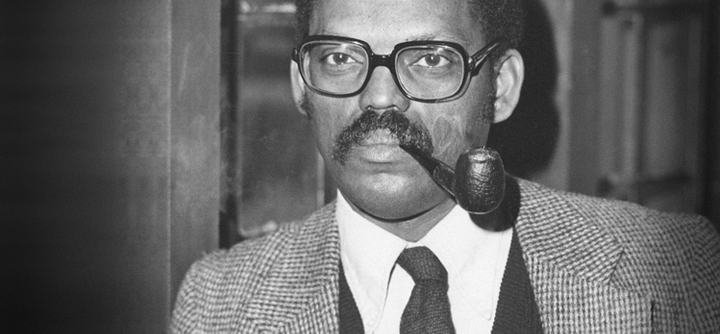

Such neglect is relatively recent. During the mid-1970s, social scientists such as Kenneth B. Clark [Life Trustee of the University], Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Lee Rainwater [AM’51, PhD’54, professor of sociology, Harvard University] forthrightly examined the cumulative effects of racial isolation and class subordination on inner-city blacks. They vividly described aspects of ghetto life that, as Rainwater observed, are usually not discussed in polite conversations. All of these studies attempted to show the connection between the economic and social environment into which many blacks are born and the creation of patterns of behavior that, in Clark’s words, frequently amounted to “self-perpetuating pathology.”

Why have scholars tended to shy away from this line of research? One reason has to do with the vitriolic attack by many blacks and liberals against Moynihan upon publication of his report in 1965—denunciations that generally focused on the author’s unflattering depiction of the black family in the urban ghetto rather than on the proposed remedies or his historical analysis of the black family’s social plight. The harsh reception accorded The Negro Family undoubtedly dissuaded many social scientists from following in Moynihan’s footsteps.

The “black solidarity” movement was also emerging during the latter half of the 1960s. A new emphasis by young black scholars and intellectuals on the positive aspect of the black experience tended to crowd out older concerns. Indeed, certain forms of ghetto behavior labeled pathological in the studies of Clark and colleagues were redefined by some during the early 1970s as “functional” because, it was argued, blacks were displaying the ability to survive and in some cases flourish in an economically depressed environment. The ghetto family was described as resilient and capable of adapting creatively to an oppressive, racist society. And the candid, but liberal writings on the inner city in the 1960s were generally denounced. In the end, the promising efforts of the early 1960s- to distinguish the socioeconomic characteristics of different groups within the black community, and to identify the structural problems of the United States economy that affected minorities-were cut short by calls for “reparations” or for “black control of institutions serving the black community.”

If this ideologically tinged criticism discouraged research by liberal scholars on the poor black family and the ghetto community, conservative thinkers were not so inhibited. From the early 1970s through the first half of the 1980s their writings on the culture of poverty and the deleterious effects of Great Society liberal welfare policies on ghetto underclass behavior dominated the public policy debate on alleviating inner-city social dislocations.

The Great Society programs represented the country’s most ambitious attempt to implement the principle of equality of life chances. However, the extent to which these programs helped the truly disadvantaged is difficult to assess when one considers the simultaneous impact of the economic downturn from 1968 to the early 1980s. Indeed, it has been argued that many people slipped into poverty because of the economic downturn and were lifted out by the broadening of welfare benefits. Moreover, the increase in unemployment that accompanied the economic downturn and the lack of growth of real wages in the 1970s, although they had risen steadily from 1960 to about 1970, have had a pronounced effect on low-income groups (especially black males).

The above analysis has certain distinct public policy implications for attacking the problems of inner-city joblessness and the related problems of poor female-headed families, welfare dependency, crime, and so forth. Comprehensive economic policies aimed at the general population but that would also enhance employment opportunities among the truly disadvantaged—both men and women—are needed. The research presented in this study suggests that improving the job prospects of men will strengthen low-income black families. Moreover, under class absent fathers with more stable employment are in a better position to contribute financial support for their families. Furthermore, since the majority of female householders are in the labor force, improved job prospects would very likely draw in others.

I have in mind the creation of a macroeconomic policy designed to promote both economic growth and a tight labor market. The latter affects the supply-and-demand ratio and wages tend to rise. It would be necessary, however, to combine this policy with fiscal and monetary policies to stimulate noninflationary growth and thereby move away from the policy of controlling inflation by allowing unemployment to rise. Furthermore, it would be important to develop policy to increase the competitiveness of American goods on the international market by, among other things, reducing the budget deficit to enhance the value of the American dollar.

In addition, measures such as on-the-job training and apprenticeships to elevate the skill levels of the truly disadvantaged are needed. I will soon discuss in another context why such problems have to be part of a more universal package of reform. For now, let me simply say that improved manpower policies are needed in the short run to help lift the truly disadvantaged from the lowest rungs of the job market. In other words, it would be necessary to devise a national labor market strategy to increase “the adaptability of the labor force to changing employment opportunities.” In this connection, instead of focusing on remedial programs in the public sector for the poor and the unemployed, emphasis would be placed on relating these programs more closely to opportunities in the private sector to facilitate the movement of recipients (including relocation assistance) into more secure jobs. Of course there would be a need to create public transitional programs for those who have difficulty finding immediate employment in the private sector, but such programs would aim toward eventually getting individuals into the private sector economy. Although public employment programs continue to draw popular support, as Margaret Weir, Ann Shola Orloff, and Theda Skocpol point out, “the must be designed and administered in close conjunction with a nationally oriented labor market strategy” to avoid both becoming “enmeshed in congressionally reinforced local political patronage” and being attacked as costly, inefficient, or” corrupt.” [Politics of Social Policy in the United States]

Since national opinion polls consistently reveal strong public support for efforts to enhance work in America, political support for a program of economic reform (macroeconomic employment policies and labor-market strategies including training efforts) could be considerably stronger than many people presently assume. However, in order to draw sustained public support for such a program, it is necessary that training or retraining, transitional employment benefits, and relocation assistance be available to all members of society who choose to use them, not just for poor minorities.

It would be ideal if problems of the ghetto underclass could be adequately addressed by the combination of macroeconomic policy, labor-market strategies, and manpower training pro grams. However, in the foreseeable future, employment alone will not necessarily lift a family out of poverty. Many families would still require income support and/or social services such as childcare. A program of welfare reform is needed, therefore, to address the current problems of public assistance, including lack of provisions for poor two-parent families, inadequate levels of support in inequities between different states, and work disincentives. A national Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) benefit standard adjusted yearly for inflation is the most minimal required change. We might also give serious consideration to programs such as the Child Support Assurance Program developed by Irwin Garfinkel [AM’67, director, School of Social Work, University of Wisconsin] and colleagues at the Institute for Research of Poverty at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. This program, currently in operation as a demonstration project in the state of Wisconsin, provides a guaranteed minimum benefit per child to single-parent families regardless of the income of the custodial parent. The state collects from the absent parent through wage withholding a sum of money at a fixed rate and then makes regular payments to the custodial parent. If the absent parent is jobless or if his or her payment from withholdings is less than the minimum, the state makes up the difference. Since all absent parents regardless of income are required to participate in this program, it is far less stigmatizing than, say, public assistance. Moreover, preliminary evidence from Wisconsin suggests that this program carries little or no additional cost to the state.

Many western European countries have programs of family or child allowances to support families. These programs provide families with an annual benefit per child regardless of the family’s income, and regardless of whether the parents are living together or whether either or both are employed. Unlike public assistance, therefore, a family allowance program carries no social stigma and has no built-in work disincentives. In this connection, Daniel Patrick Moynihan has recently observed that a form of family allowance is already available to American families with the standard deduction and the Earned Income Tax Credit, although the latter can only be obtained by low-income families. Even though both have been significantly eroded by inflation, they could represent the basis for a more comprehensive family allowance program that approximates the European model.

Neither the Child Support Assurance Program under demonstration in Wisconsin nor the European family allowances program is means tested; that is, they are not targeted at a particular income group and therefore do not suffer the degree of stigmatization that plagues public assistance programs such as AFDC. More important, such universal programs would tend to draw more political support from the general public because the programs would be available not only to the poor but to the working- and middle-class segments as well. And such programs would not be readily associated with specific minority groups. Nonetheless, truly disadvantaged groups would reap disproportionate benefits from such programs because of the groups’ limited alternative economic resources. For example, low-income single mothers could combine work with adequate guaranteed child support and/or child allowance benefit and therefore escape poverty and avoid public assistance.

Finally, the question of childcare has to be addressed in any program designed to improve the employment prospects of women and men. Because of the growing participation of women in the labor market, adequate childcare has been a topic receiving increasing attention in public policy discussions. For the overwhelmingly female-headed ghetto underclass families, access to quality childcare becomes a critical issue if steps are taken to move single mothers into education and training programs and/or full- or part-time employment. However, I am not recommending government-operated childcare centers. Rather it would be better to avoid additional federal bureaucracy by seeking alternative and decentralized forms of child care such as expanding the child care tax credit, including three- and four-year olds in preschool enrollment, and providing child care subsidies to the working-poor parents.

If the truly disadvantaged reaped disproportionate benefits from a child support enforcement program, child allowance program, and child care strategy, they would also benefit disproportionately from a program of balanced economic growth and tight-labor market policies because of their greater vulnerability to swings in the business cycle of changes in economic organization, including the relocation of plants and the use of labor-saving technology. It would be shortsighted to conclude, therefore, that universal programs (i.e., programs not targeted at any particular group) are not designed to help address in a fundamental way some of the problems of the truly disadvantaged, such as the ghetto underclass.

By emphasizing universal programs as an effective way to address problems in the inner city created by historic racial subjugation, I am recommending a fundamental shift from the traditional race-specific approach of addressing such problems. It is true that problems of joblessness and related woes such as poverty, teenage pregnancies, out-of-wedlock births, female-headed families, and welfare dependency are, for reasons of historic racial oppression, disproportionately concentrated in the black community. And it is important to recognize the racial differences in rates of social dislocation so as not to obscure problems currently gripping the ghetto underclass. However, as discussed above, race-specific policies are often not designed to address fundamentally problems of the truly disadvantaged. Moreover, as also discussed above, both race-specific and targeted programs based on the principle of equality of life chances (often identified with a minority constituency) have difficulty sustaining widespread public support.

Does this mean that targeted programs of any kind would necessarily be excluded from a package highlighting universal programs of reform? On the contrary, as long as a racial division of labor exists and racial minorities are disproportionately concentrated in low-paying positions, antidiscrimination and affirmative action programs will be needed even though they tend to benefit the more advantaged minority members. Moreover, as long as certain groups lack the training, skills, and education for jobs, manpower training and education programs targeted at these groups will also be needed, even under a tight-labor market situation. For example, a program of adult education and training may be necessary for some ghetto underclass males before they can either become oriented to or move into an expanded labor market. Finally, as long as some poor families are unable to work because of physical or other disabilities, public assistance would be needed even if the government adopted a program of welfare reform that included child support enforcement and family allowance provisions.

For all these reasons, a comprehensive program of economic and social reform (highlighting macroeconomic policies to promote balanced economic growth and create a tight-labor-market situation, a nationally oriented labor market strategy, a child support assurance program, a child care strategy, and a family allowances program) would have to include targeted programs, both means-tested and race-specific. However, the latter would be considered an offshoot of and indeed secondary to the universal programs. The important goal is to construct an economic-social reform program in such a way that the universal programs are seen as the dominant and most visible aspects by the general public. As the universal programs draw support from a wider population, the targeted programs included in the comprehensive reform package would be indirectly supported and protected. Accordingly, the hidden agenda for liberal policymakers is to improve the life chances of truly disadvantaged groups such as the ghetto underclass by emphasizing programs to which the more advantaged groups of all races and class backgrounds can positively relate.

I am reminded of Bayard Rustin’s plea during the early 1960s that blacks ought to recognize the importance of fundamental economic reform (including a system of national economic planning along with new education, manpower, and public works programs to help reach full employment) and the need for a broad-based political coalition to achieve it. And since an effective coalition will in part depend upon how the issues are defined, it is imperative that the political message underline the need for economic and social reforms that benefit all groups in the United States, not just poor minorities. Politicians and civil rights organizations, as two important examples, ought to shift or expand their definition of America’s racial problems and broaden the scope of suggested policy programs to address them. They should, of course, continue to fight for an end to racial discrimination. But they must also recognize that poor minorities are profoundly affected by problems in America that go beyond racial considerations. Furthermore, civil rights groups should also recognize that the problems of societal organization in America often create situations that enhance racial antagonisms between the different racial groups in central cities that are struggling to maintain their quality of life, and that these groups, although they appear to be fundamental adversaries, are potential allies in a reform coalition because of their problematic economic situations.

The difficulties that a progressive reform coalition would confront should not be underestimated. It is much easier to produce major economic and social reform in countries such as Sweden; Norway, Austria, the Netherlands, and West Germany than in the United States. What characterizes this group of countries, as demonstrated in the important research of Harold Wilensky [AM’49, PhD’55, research sociologist and professor of political science, University of California at Berkeley], is the interaction of solidly organized, generally centralized, interest Groups—particularly professional, labor, and employer associations with a centralized or quasi-centralized government either compelled by law or obliged by informal agreement to take the recommendations of the interest group into account or to rely on their counsel. This arrangement produces a consensus-making organization working generally within a public framework to bargain and produce policies on present-day political-economy issues such as full employment, economic growth, unemployment, wages, prices, taxes, balance of payments, and social policy (including various forms of welfare, education, health, and housing policies).

In all of these countries, called “corporatist democracies” by Wilensky, social policy is integrated with economic policy. This produces a situation whereby, in periods of rising aspirations and slow economic growth, labor—concerned with wages, working conditions, and social security—is compelled to be attentive to the rate o productivity, the level of inflation, and the requirements of investments, and employers—concerned with profits, productivity, and investments—are compelled to be attentive to issues of social policy.

The corporatist democracies, which are in a position to develop a new consensus on social and economic policies in the face of declining economies because channels for bargaining and influence are firmly in place, stand in sharp contrast to the decentralized and fragmented political economies of the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. In these latter countries—none of which is a highly progressive welfare state— the proliferation of interest groups is not restrained by the requisites of national trade-offs and bargaining, which therefore allows parochial single issues to move to the forefront and thereby exacerbates the advanced condition of political immobilism. Reflecting the rise of single-issue groups has been the steady deterioration of political organizations and the decline of traditional allegiance to parties among voters. Moreover, there has been a sharp increase in the influence of the mass media, particularly the electronic media, in politics and culture. These trends, typical of all Western democracies, are much more salient in countries such as the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom because their decentralized and fragmented political economies magnify the void created by the decline of political parties- a void that media and strident, single-issue groups rush headlong to fill.

I raise these issues to underline some of the problems that a political coalition dedicated to developing and implementing a progressive policy agenda will have to confront. It seems imperative that, in addition to outlining a universal program of reform including policies that could effectively address inner-city social dislocations, attention be given to the matter of erecting a national bargaining structure to achieve a sufficient consensus on the program of reform.

It is also important to recognize that just as we can learn from knowledge about the efficacy of alternative bargaining structures, we can also benefit from knowledge of alternative approaches to welfare and employment policies. Here we fortunately have the research of Alfred J. Kahn and Sheila Kamerman, which has convincingly demonstrated that countries that rely the least on public assistance, such as Sweden, West Germany, and France, provide alternative income transfers (family allowances, housing allowances, child support, unemployment assistance), stress the use of transfers to augment both earnings and transfer income, provide both child care services and day-care programs, and emphasize labor-market policies to enhance high employment. These countries, therefore, “provide incentives to work, supplement the use of social assistance generally because, even when used, it is increasingly only one component, at most, of a more elaborate benefit package.” By contrast, the United States relies more heavily than all the other countries (Sweden, West Germany, France, Canada, Austria, the United Kingdom, and Israel) on public assistance to aid poor families. “The result is that these families are much worse off than they are in any of the other countries.”

In other words, problems such as poverty, joblessness, and long-term welfare dependency in the United States have not been addressed with the kinds of innovative approaches found in many western European democracies. “The European experience,” argue Kamerman and Kahn, “suggests the need for a strategy that includes income transfers, child care services, and employment policies as central elements.” The cornerstone of social policy in these countries is employment and labor-market policies. “Unless it is possible for adults to manage their work and family lives without undue strain on themselves and their children,” argue Kamerman and Kahn, “society will suffer a significant loss in productivity, and an even more significant loss in the quantity and quality of future generations.”

The social policy that I have recommended above also would have employment and labor-market policies as its fundamental foundation. For in the final analysis neither family allowance and child support assurance programs, nor means-tested public assistance and manpower training and education programs, can be sustained at adequate levels if the country is plagued with prolonged periods of economic Stagnation and joblessness.

The program of economic and social reform outlined above will help address the problems of social dislocation plaguing the ghetto underclass. I make no claims that such programs will lead to a revitalization of neighborhoods in the inner city, reduce the social isolation, and thereby recapture the degree of social organization that characterized these neighborhoods in earlier years. However, in the long run these programs will lift the ghetto underclass from the throes of long-term poverty and welfare dependency and provide them with the economic and educational resources that would expand the limited choices they now have with respect to living arrangements. At the present time many residents of isolated inner-city neighborhoods have no other option but to remain in those neighborhoods. As their economic and educational resources improve they will very likely follow the path worn by many other former ghetto residents and move to safer or more desirable neighborhoods.

It seems to me that the most realistic approach to the problems of concentrated inner-city poverty is to provide ghetto underclass families and individuals with the resources that promote social mobility. Social mobility leads to geographical mobility. This raises a question about the ultimate effectiveness of the so-called self-help programs to revitalize the inner city, programs pushed by conservative and even some liberal black spokespersons. In many inner-city neighborhoods problems such as joblessness are so overwhelming and require such a massive effort to restabilize institutions and create a social and economic milieu necessary to sustain such institutions (e.g., the reintegration of the neighborhood with working- and middle-class blacks and black professionals) that it is surprising that advocates of black self-help have received so much serious attention from the media and policymakers.

Of course some advocates of self help subscribe to the thesis that problems in the inner city are ultimately the product of ghetto-specific culture and that it is the cultural values and norms in the inner city that must be addressed as part of a comprehensive self-help program. However, cultural values emerge from specific circumstances and life chances and reflect an individual’s position in the class structure. They therefore do not ultimately determine behavior. If ghetto underclass minorities have limited aspirations, a hedonistic orientation toward life, or lack of plans for the future, such outlooks ultimately are the result of restricted opportunities and feelings of resignation originating from bitter personal experiences and a bleak future. Thus the inner-city social dislocations emphasized in this study (joblessness, crime, teenage pregnancies, out-of-wedlock births, female-headed families, and welfare dependency) should be analyzed not as cultural aberrations but as symptoms of racial-class inequality. It follows, therefore, that changes in the economic and social situations of the ghetto underclass will lead to changes in cultural norms and behavior patterns. The social policy program outlined above is based on this idea.

Before I take a final look, by way of summary and conclusion, at the important features of this program, I ought briefly to discuss an alternative public agenda that could, if not challenged, dominate the public policy discussion of underclass poverty in the next several years.

In a recent book, Lawrence Mead [Beyond Entitlement: The Social Obligations of Citizenship] contends that “the challenge to welfare statesmanship is not so much to change the extent of benefits as to couple them with serious work and other obligations that would encourage functioning and thus promote the integration of recipients.” He argues that the programs of the Great Society failed to overcome poverty and, in effect, increased dependency because the “behavioral problems of the poor” were ignored. Welfare clients received new services and benefits but were not told “with any authority that they ought to behave differently.” Mead attributes a good deal of the welfare dependency to a sociological logic ascribing the responsibilities for the difficulties experienced by the disadvantaged entirely to the social environment, a logic that still “blocks government from expecting or obligating the poor to behave differently than they do.”

Mead believes that there is a disinclination among the underclass to either accept or retain many available low-wage jobs. The problem of nonwhite unemployment, he contends, is not a lack of jobs, but a high turnover rate. Mead contends that because this kind of joblessness is not affected by changes in the overall economy, it would be difficult to blame the environment. While not dismissing the role discrimination may play in the low wage sector, Mead argues that it is more likely that the poor are impatient with the working conditions and pay of menial jobs and repeatedly quit in hopes of finding better employment. At the present time, “for most job seekers in most areas, jobs of at least a rudimentary kind are generally available.” For Mead it is not that the poor do not want to work, but rather that they will work only under the condition that others remove the barriers that make the world of work difficult. “Since much of the burden consists precisely in acquiring skills, finding jobs, arranging child care, and so forth,” states Mead, “the effect is to drain work obligation of much of its meaning.”

In sum, Mead believes that the programs of the Great Society have exacerbated the situation of the underclass by not obligating the recipients of social welfare programs to behave according to mainstream norms- completing school, working, obeying the law, and so forth. ‘Since virtually nothing was demanded in return for benefits, the underclass remained socially isolated and could not be accepted as equals.

If any of the social policies recommended by conservative analysts are to become, serious candidates for adoption as national public policy, they will more likely be based on the kind of argument advanced by Mead in favor of mandatory workfare. The laissez-faire social philosophy represented by Charles Murray is not only too extreme to be seriously considered by most policymakers, but the premise upon which it is based is vulnerable to the kind of criticism raised by Sheldon Danziger and Peter Gottschalk [in “Social Programs—A Partial Solution to, But Not a Cause of Poverty: An Alternative to Charles Murray’s View,” Challenge Magazine, May–June/85] namely, that the greatest rise in black joblessness and female-headed families occurred during the very period (1972- 1980) when the real value of AFDC plus food stamps plummeted because states did not peg benefit levels to inflation.

Mead’s arguments, on the other hand, are much more subtle and persuasive. If his and similar arguments in support of mandatory workfare are not adopted wholesale as national policy, aspects of his theoretical rationale on the social obligations of citizenship could, as we shall see, help shape a policy agenda involving obligational state programs.

Nonetheless, whereas Mead speculates that jobs are generally available in most areas and therefore one must turn to behavioral explanations for the high jobless rate among the underclass, data presented [earlier in this book] reveal (1) that substantial job losses have occurred in the very industries in which urban minorities are heavily concentrated and substantial employment gains have occurred in the higher education-requisite industries that have relatively few minority workers; (2) that this mismatch is most severe in the Northeast and Midwest (regions that also have had the sharpest increases in black joblessness and female-headed families); and (3) that the current growth in entry-level jobs, particularly in the service establishments, is occurring almost exclusively outside the central cities where poor minorities are concentrated. It is obvious that these findings raise serious questions not only about Mead’s assumptions regarding poor minorities, work experience, and jobs, but also about the appropriateness of his policy recommendations. Nonetheless, there are clear signs that a number of policymakers are now moving in this direction, even liberal policymakers who, while considering the problems of poor minorities from the narrow visions of race relations and the War on Poverty, have become disillusioned with Great Society-type programs. The emphasis is not necessarily on mandatory workfare, however. Rather the emphasis is on what Richard Nathan has called “new-style workfare,” which represents a synthesis of liberal and conservative approaches to obligational state programs. Let me briefly elaborate.

In the 1970s the term workfare was narrowly used to capture the idea that welfare recipients should be required to work, even to do make-work if necessary, in exchange for receiving benefits. This idea was generally rejected by liberals and those in the welfare establishment. And no workfare program, not even Governor Ronald Reagan’s 1971 program, really got off the ground. However, by 1981 President Ronald Reagan was able to get congressional approval to include a provision in the 1981 budget allowing states to experiment with new employment approaches to welfare reform. These approaches represent the “new-style workfare.” More specifically, whereas workfare in the 1970s was narrowly construed as “working off” one’s welfare grant, the new-style workfare “takes the form of obligational state programs that involve an array of employment and training services and activities- job search, job training, education programs, and also community work experience.”

According to Nathan, “we make our greatest progress on social reform in the United States when liberals and conservatives find common ground. New-style workfare embodies both the caring commitment of liberals and the themes identified with conservative writers like Charles Murray, George Gider, and Lawrence Mead.” On the one hand, liberals can relate to new style workfare because it creates short-term entry-level positions very similar to the “CETA public service jobs we thought we had abolished in 1981 “; it provides a convenient” political rationale and support for increased funding for education and training programs”; and it targets these programs at the most disadvantaged, thereby correcting the problem of “creaming” that is associated with other employment and training programs. On the other hand, conservatives can relate to new-style workfare because “it involves a strong commitment to reducing welfare dependency on the premise that dependency is bad for people, that it undermines their motivation to self-support and isolates and stigmatizes welfare recipients in a way that over a long period feeds into and accentuates the underclass mind set and condition.”

The combining of liberal and conservative approaches does not, of course, change the fact that the new-style workfare programs hardly represent a fundamental shift from the traditional approaches to poverty in America. Once again the focus is exclusively on individual characteristics- whether they are construed in terms of lack of training, skills, or education, or whether they are seen in terms of lack of motivation or other subjective traits. And once again the consequences of certain economic arrangements on disadvantaged populations in the United States are not considered in the formulation and implementation of social policy. “As long as the unemployment rate remains high in many regions of the country, members of the underclass are going to have a very difficult time competing successfully for the jobs that are available,” states Robert D. Reischauer. “No amount of remedial education, training, wage subsidy, or other embellishment will make them more attractive to prospective employers than experienced unemployed workers.” As Reischauer appropriately emphasizes, with a weak economy “even if the workfare program seems to be placing its clients successfully, these participants may simply be taking jobs away from others who are nearly as disadvantaged. A game of musical underclass will ensue as one group is temporarily helped, while another is pushed down into the underclass.”

If new-style workfare will indeed represent a major policy thrust in the immediate future, I see little prospect for substantially alleviating inequality among poor minorities if such a workfare program is not part of a more comprehensive program of economic and social reform that recognizes the dynamic interplay between societal organization and the behavior and life chances of individuals and groups- a program, in other words, that is designed to both enhance human capital traits of poor minorities and open up the opportunity structure in the broader society ad economy to facilitate social mobility. The combination of economic and social welfare policies discussed in the previous section represents, from my point of view, such a program.

I have argued that the problems of the ghetto underclass can be most meaningfully addressed by a comprehensive program that combines employment policies with social welfare policies and that features universal as opposed to race- or group-specific strategies. On the one hand, this program highlights macroeconomic policy to generate a tight labor market and economic growth; fiscal and monetary policy not only to stimulate noninflationary growth, but also increase the competitiveness of American goods on both the domestic and international markets; and a national labor-market strategy to make the labor force more adaptable to changing economic opportunities. On the other hand, this program highlights a child support assurance program, a family allowance program, and a childcare strategy.

I emphasized that although this program also would include targeted strategies—both means-tested and race-specific—they would be considered secondary to the universal programs so that the latter are seen as the most visible and dominant aspects in the eyes of the general public. To the extent that the universal programs draw support from a wider population, the less visible targeted programs would be indirectly supported and protected. To repeat, the hidden agenda for liberal policymakers is to enhance the chances in life for the ghetto underclass by emphasizing programs to which the more advantaged groups of all class and racial backgrounds can positively relate.

Before such programs can be seriously considered, however, cost has to be addressed. The cost of programs to expand social and economic opportunity will be great, but it must be weighed against the economic and social costs of a do-nothing policy. As S. A. Levitan and C. M. Johnson [in Beyond the Safety Net: Reviving the Promising of Opportunity in America] have pointed out, “the most recent recession cost the nation an estimated $300 billion in lost income and production, and direct outlays for unemployment compensation totaled $30 billion in a single year. A policy that ignores the losses associated with slack labor markets and forced idleness inevitably will underinvest in the nation’s labor force and future economic growth.” Furthermore, the problem of an annual budget deficit of over 200 billion dollars (driven mainly by the peacetime military buildup and the Reagan administration’s tax cuts) and the need for restoring the federal tax base and adopting a more balanced set of budget priorities have to be tackled if we are to achieve significant progress on expanding opportunities as soon as possible.

In the final analysis, the pursuit of economic and social reform ultimately involves the question of political strategy. As the history of social provision so clearly demonstrates, universalistic political alliances, cemented by policies that provide benefits directly to wide segments of the population, are needed to work successfully for major reform. The recognition among minority leaders and liberal policymakers of the need to expand the War on Poverty and race relations visions to confront the growing problems of inner-city social dislocations will provide, I believe, an important first step toward creating such an alliance.