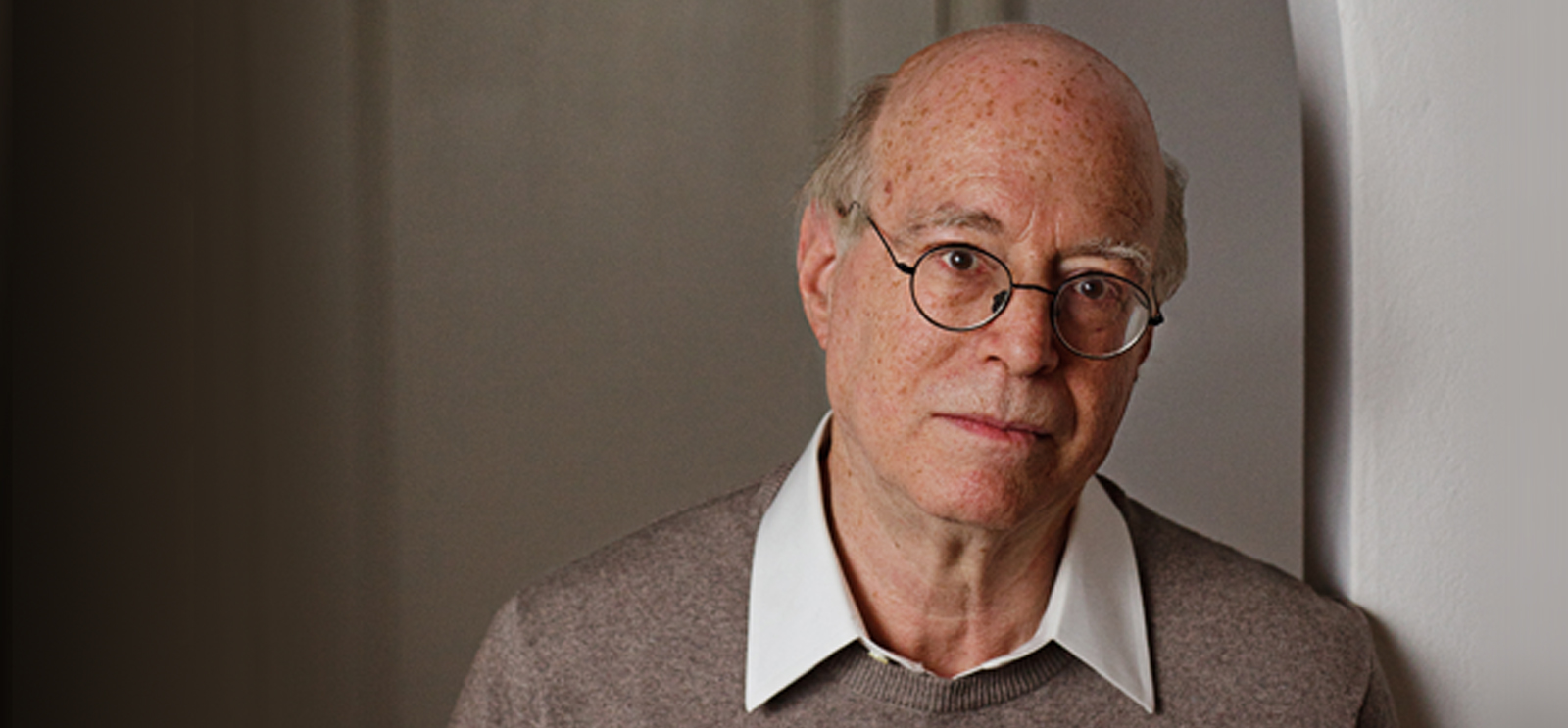

Richard Sennett, AB’64, has published 15 books on labor, cities, and culture. His scholarship draws on sociology, history, philosophy, and psychoanalytic theory. But when writing, he keeps a very specific person in mind. “My ideal reader is a woman nuclear scientist,” says Sennett. “And she always wants to know two things: Is this interesting? And does it matter?”

As a grad student at Harvard, Sennett had a scientist friend who asked those questions before reading his work. Her challenge has stayed with him for more than 40 years. Sennett writes and lectures widely on the ways cities are organized and the social and emotional consequences of contemporary capitalism. Based at the London School of Economics and New York University, he has sought to be interesting and relevant to what he calls “the intelligent general reader.”

At a time of global recession and uncertainty, Sennett’s 2008 book The Craftsman—published in five languages—has resonated with a broad audience. Defining craftsmanship as “an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake,” the book traces the connections between craftsmanship, work, and ethical values from ancient times to the present.

Modern craftspeople include musicians, glassblowers, teachers, doctors, parents, and open-source software writers, Sennet told a packed auditorium at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago one frigid night last winter. Every person has the raw abilities to become a good craftsman, he said in his lecture, but Western societies have not always nurtured the impulse.

Studying craftsmanship over the centuries, Sennett found that it flourishes in communities with strong social bonds—and in organizations that encourage collaboration. In the modern economy, powerful forces threaten both craft and cooperation, he believes. The trends are familiar to anyone who has lately done, lost, or searched for good work: Large industries no longer provide critical masses of stable jobs in the United States and Europe. As jobs move elsewhere, fewer companies are willing to make long-term investments in workers. Work is increasingly short term and project based, so people have many jobs in a lifetime.

In short, skilled workers at all levels have found that “craft does not protect them,” Sennett writes; they “risk the prospect of losing employment to a peer in India or China who has the same skills but works for lower pay.” Even educated professionals and once-secure managers have joined a class that academics call “the precariat.” As Sennett puts it, “job loss is no longer merely a working-class problem.”

The Craftsman is the first book in a trilogy Sennett is writing about “the skills people need to sustain everyday life.” The books explore material culture—that is, the objects, tools, and machines we create and how we interact with them. Both humanists and social scientists have embraced such topics, he explains, “in part because we’ve got a whole new set of material tools, which are these communications machines; in part because our country isn’t making things much anymore.” Globalization and technological change have shifted production away from the United States, with repercussions for workers and cities. “We had the fantasy when this started that we’d send [the Chinese] the low-level crap production and we’d keep the good stuff for ourselves,” he says. “It hasn’t worked out that way.”

In his own life and career, Sennett had to adapt to shifting circumstances. The only child of a single mother, Sennett was three when they moved into Chicago’s Cabrini Green housing project in 1946. “People always think about Cabrini Green as exclusively black. It wasn’t in its early days,” he says. “And it wasn’t a picnic, but people developed everyday rituals to make sure that you’d get to and from school, that things didn’t go out of order. We were little kids, and we became street smart.”

His mother, Dorothy Skolnik Sennett, was a social worker who attended the University’s School of Social Service Administration in 1939–40. “She studied with Charlotte Towle, a great social worker and heir to Jane Addams,” he says. Sennett had been playing the cello since the age of five; when he was eight or nine, he and his mother left Chicago and eventually settled in Washington, DC. In 1960 he returned to Chicago as a teenager to study with Frank Miller, principal cellist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. “I would have been very happy to just study with him privately, but I would have been instantly drafted. So I went to the University of Chicago,” he says with a laugh, “and I loathed it.”

Sennett continued his cello studies with Miller, but he remembers the Hyde Park campus as isolated from the rest of the city during the 1960s: “Its relations with the neighborhood were pretty tense and sometimes quite violent. Getting to and from downtown, which is where I spent a lot of my time, was difficult. The University at that time was not very open to the arts.” He played early music with the Collegium Musicum (“It was a disaster,” he says) and chamber music with his friend Leon Botstein, AB’67, a violinist who is now the president of Bard College and music director of the American Symphony Orchestra. “I don’t know what Chicago is like today, but I regretted very much the almost snobbism about the practical arts. In the music department there were music theorists who couldn’t play the piano.”

Although he chafed against the general-education requirements of the post-Hutchins College, Sennett, who earned a history degree, connected with Christian Mackauer, his Western Civilization teacher. “He was a kindly man and very worldly, and he introduced me to Hannah Arendt,” Sennett says. “Those were two older teachers that I really found to be wonderful supports.”

In his second year, Sennett left the College to study cello and conducting at Juilliard. Six months after arriving in New York City, he was served a draft notice. Because he could get an educational deferment and avoid serving in Vietnam only if he returned to the University, he explains, “I went back to Chicago, and I finished up.” He kept playing the cello but developed carpal tunnel syndrome, and in 1964 he had a hand operation that went wrong. “It was pretty clear to me—and this was not a great moment of my life—that I wasn’t going to be a professional musician.”

Instead, Sennett pursued a PhD in the history of American civilization at Harvard, working with the sociologist David Riesman (who taught at Chicago until 1958). “I was going to do a book comparing American chamber music to American jazz music in the 1930s,” Sennett says. “Then the ’60s happened.” He became interested in cities and ways that social class, economic opportunity, and family life played out in urban communities. “Since I wasn’t going to be able to perform, I sort of just moved into sociology.”

For an accidental academic, Sennett has been prolific. Before turning 30 he published five books, including The Uses of Disorder (1970), still considered influential in urban sociology. “It was an unusual book in that it blended many different types of thinking, from psychoanalytic work to social theory,” says Robert Sampson, a former Chicago and now Harvard sociologist who studies crime and the social organization of cities. “But what really intrigued me is that he had a counterintuitive idea about the nature of disorder and specifically its positive aspects.” For personal growth, Sennett argued, people need challenge, difference, and diversity—types of “disorder” they are more likely to find in chaotic cities than in orderly suburban communities.

Researching his next book, The Hidden Injuries of Class (1972), with coauthor Jonathan Cobb, Sennett cut his teeth as an ethnographer. Interviewing 150 semiskilled workers in Boston, he uncovered a theme—the personal effects of inequality—that made the book a classic and reappeared in his later scholarship. He published four more sociological studies and three novels before producing a trio of books—The Corrosion of Character (1998), Respect, in an Age of Inequality (2003), and The Culture of the New Capitalism (2005)—that aimed to document how global economic changes upended traditional American notions of trust, mutual respect, and merit in the workplace. Sennett tried to show how the massive flow of global capital into national markets since the mid-1970s and the instability of the new economy affected workers both socially and emotionally.

Some social scientists discount Sennett’s work because it relies more on stories and interviews—with IBM executives, Korean grocers, or counselors at a New York City job center—than on quantitative empirical data. He prefers philosophy and history to statistics or network modeling. “I think that many sociologists would consider him a general cultural critic rather than a sociologist per se,” says Chicago sociology professor Andrew Abbott, AM’75, PhD’82. Others suggest that Sennett’s approach is interesting—and it matters—because it humanizes the study of society. “The great strength of Richard’s books is their belief in the importance of narrative in the creation of values, norms, and concepts,” says Homi Bhabha, a former UChicago English professor who directs the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard.

Sennett’s latest book, Together: The Rituals, Pleasures, and Politics of Cooperation (due out in December), explores cooperation as a “social craft.” The ability to understand and respond to others to get things done, he argues, is innate to humans and necessary for survival. Apprentices and masters cooperated in medieval guilds; American soldiers and officers cooperated on the battlefield during World War II. When the latter returned to civilian life, writes Sennett, their shared experience helped smooth interactions on the factory floor and diminish class conflict.

People hone a craft—and get better at cooperation—when they have time to practice, mentors to learn from, and opportunities to improve through trial and error. Interviewing white-collar workers who lost their jobs on Wall Street after the 2008 financial meltdown, Sennett and student researchers found that the same dynamics that discourage craft make cooperation fragile. Especially in the financial sector, institutions are less stable; companies may merge, dissolve, or shed workers rather than train them to learn new skills. Competition and the focus on short-term profit and fast transactions erode social bonds. Work teams come together “long enough to get a job done—but not so long that the members of the team become too attached to one another,” Sennett writes. Employees may fake cooperation to impress managers and coworkers, and loyalty is a quaint relic of the past. When crisis hits, “team spirit suddenly collapses; people seek cover and deniability by shifting blame to other team members.”

Back-office employees on Wall Street, people who managed transactions, prepared documents for audit, and processed purchases, Sennett says, “were craftsmen of sorts. They were skilled, and they took pride in their work.” Yet many believed their bosses understood little about the mechanics of the firms they were managing before the crash. Indeed, midlevel workers saw “an inverse relationship between competence and hierarchy.” The wide gap in earnings between CEOs and employees has fueled resentment and further damaged trust and respect. Overall, Sennett says, “Inequality is really getting in the way of people working together.”

If Sennett’s worldview sounds bleak, that’s misleading. From his book-lined office overlooking a busy Greenwich Village street, he waxes optimistic about the future of cooperation in urban communities. “I actually think that the bonds of civility among people in the cities can be much stronger than they are in small places. You have to learn how to deal with strangers at work, school, when you go to the hospital,” he says, as horns honk below. He hopes that American cities will create a civic culture that helps people of diverse backgrounds to get along in everyday life. “The main thing is economic and has to do with housing,” he says, citing New York City, where rent control fosters economically mixed neighborhoods, and the Netherlands, where public assistance allows people of different income levels to live in the same community.

For Sennett, cities are a family business of sorts. His wife, sociologist Saskia Sassen, taught at Chicago for nearly a decade before joining the Columbia faculty in 2007. Her 1991 book, The Global City, documented how New York, London, and Tokyo became hubs of the global economy. “We give lectures together,” he says. “It’s a very strange event to people, because I’m completely humanistic and she’s a hardcore numbers person—with charts, endless charts.” After Britain’s summer riots, the pair coauthored a New York Times op-ed suggesting that extreme inequality and politicians’ eagerness to cut budgets for local police and community services helped fuel the violence. “Britain’s current crisis should cause us to reflect on the fact that a smaller government can actually increase communal fear and diminish our quality of life,” they wrote. “Is that a fate America wishes upon itself?”

If Sennett criticizes the political right for defunding urban institutions, he also chides the left in the United States and Europe for failing to make itself “a creditable voice for reform.” To regain ordinary people’s trust, American progressives should invest energy and funds in local issues rather than national electoral politics, he believes. In the spirit of community organizers from Jane Addams to Saul Alinsky, PhB’30—a family friend—Sennett emphasizes the need for cooperation that can transform daily life and interpersonal relations: “It’s a matter of putting the social back into socialism,” he wrote in a July essay in the Nation.

In The Craftsman, Sennett places himself within the philosophical tradition of the pragmatists, whose “animating impulse remains to engage with ordinary, plural constructive human activities.” Although Sennett calls himself “an old lefty,” the New Yorker critic Kelefa Sanneh has suggested that his midlife “call to craft is in some ways a conservative call: it asks workers to seek fulfillment through personal diligence, not politics.” The assessment is fair enough, says Sennett. “I am not very politically minded. My work focuses on civil society, and that’s its strength and its weakness.”

In his own life, Sennett has experienced the pleasures of cooperation and of doing a job well for its own sake. He practices the cello and plays with informal chamber groups; he shops, cleans, and cooks for dinner parties. And whenever he writes he remembers his friend, the nuclear scientist. “She was much smarter than I, so I’ve always thought it was a really good guide to think about someone who’s your equal—to write out rather than down.” What matters most, he says, “is being part of a public discussion with other people, rather than trying to influence the powerful.”

Sennett hopes that the final book in his trilogy, based on ethnographies of four London communities, will generate worthwhile ideas about how cities might be better crafted. Even if answers prove elusive, he is likely to be comfortable with ambiguity. “Oftentimes, we want to get a picture of everything—what should be done, what’s wrong, how to go forward, and so on—and we can’t have that,” he says. “Every act of writing is incomplete and should be incomplete. ... Nothing is ever settled in life.”