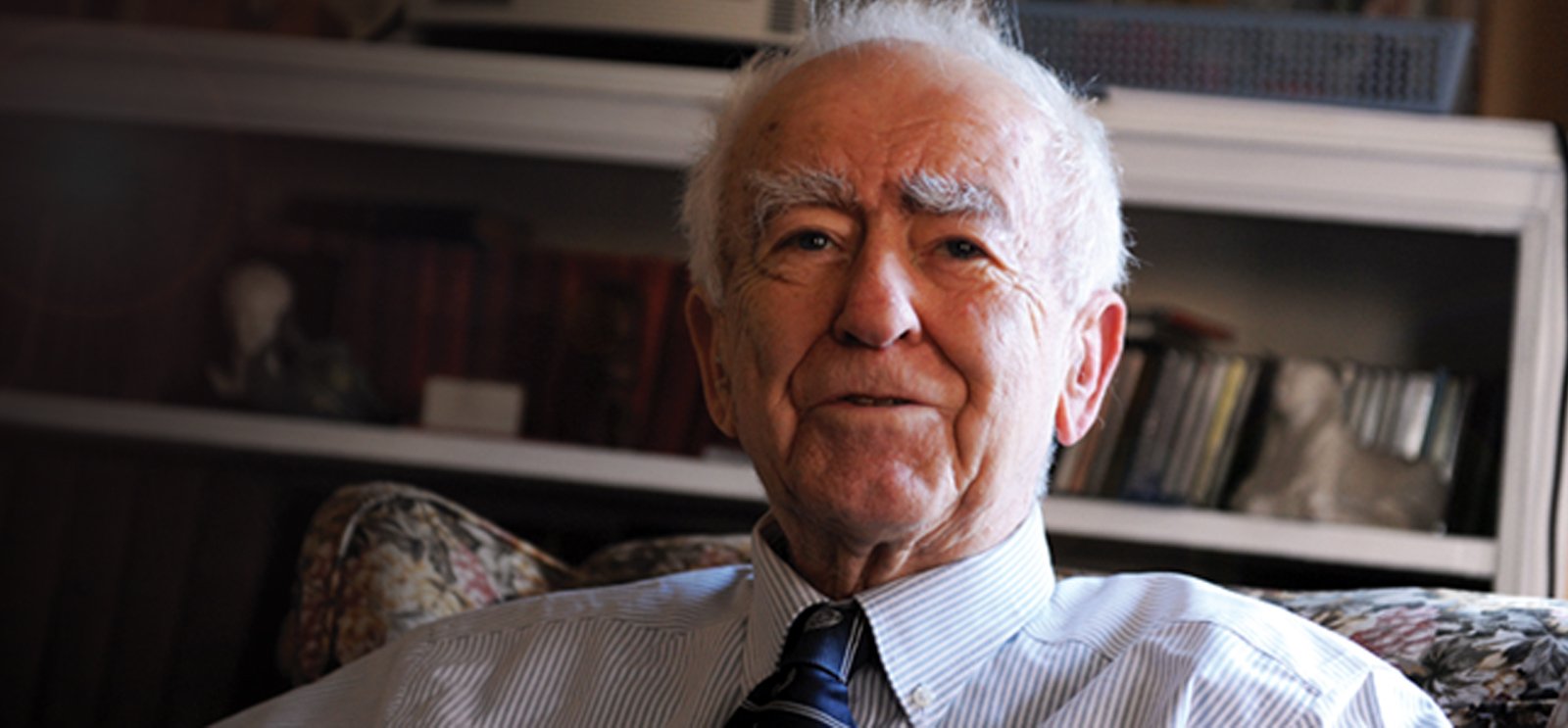

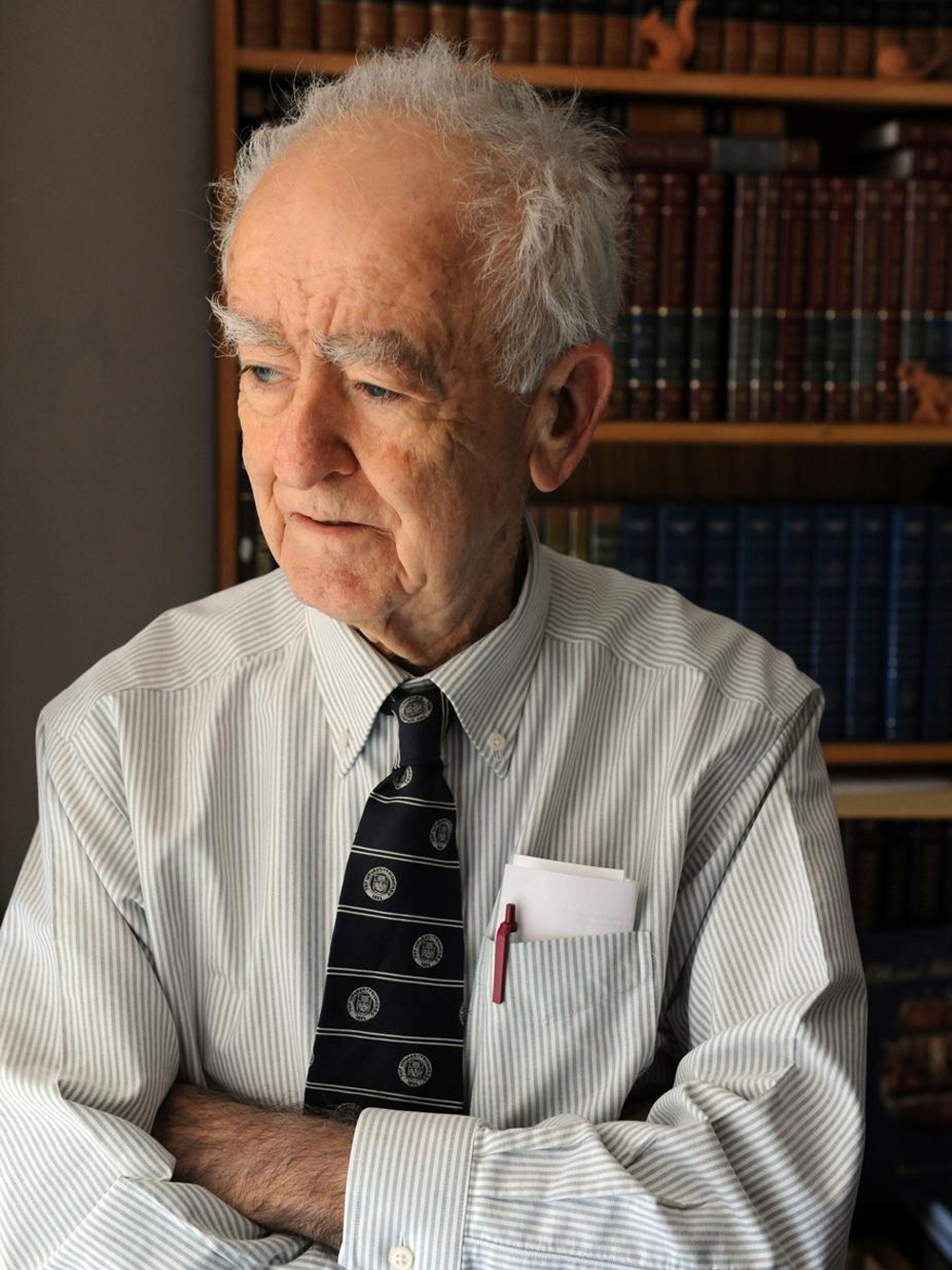

Justice Hugo Black once called George Anastaplo, AB’48, JD’51, PhD’64, “too stubborn for his own good.” Sixty-some years later, Anastaplo sits in a basement room in the Gleacher Center, in downtown Chicago, surrounded by a dozen adult-education students, the picture of cheerful amiability. At 86 years old, Anastaplo has taught in the University of Chicago’s Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults for 55 years. A small man with white hair and clear gray eyes, wearing running shoes and an old tweed jacket, Anastaplo is lively and relaxed. A photocopy of Emerson’s essay “Friendship” lies on the table in front of him.

“I was appalled by how elitist Emerson was in his view of friendship,” says one student, a middle-aged woman.

Anastaplo’s eyes light up. He leans forward, and a smile tugs at the corners of his mouth. “You were appalled?” he says. She reads from a passage in which Emerson writes, “‘I do then with my friends as I do with my books. I would have them where I can find them, but I seldom use them.’ Give me a break!” she exclaims, rolling her eyes. Delighted, Anastaplo swivels his head around the room. “Any reactions?”

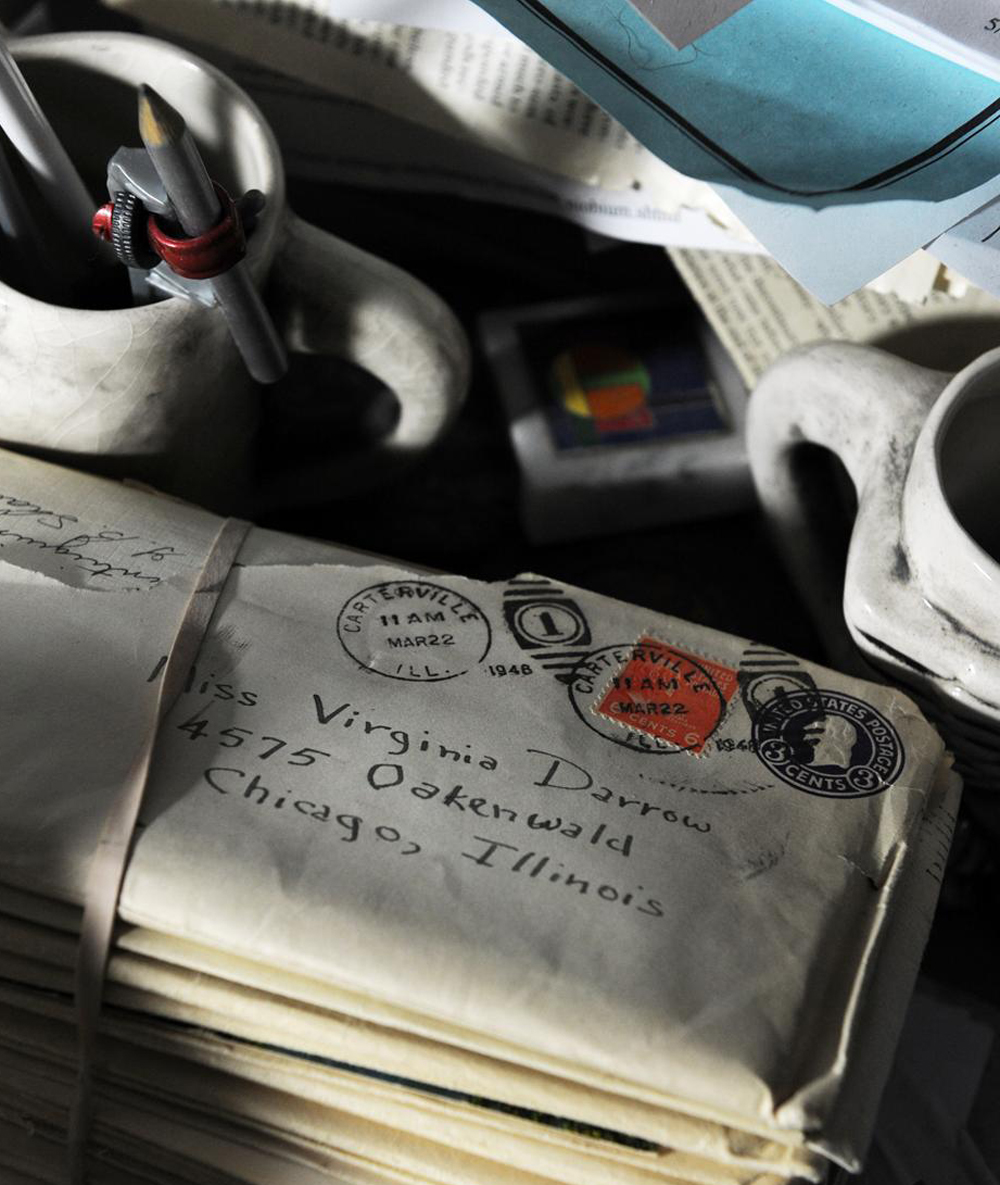

This was not the life Anastaplo envisioned. On the morning of November 10, 1950, three days after his 25th birthday, he put on a coat and tie and headed downtown to the offices of the Chicago Bar Association, on LaSalle Street, for what he assumed would be the last step to launching a legal career in Illinois. The son of Greek immigrants from downstate Carterville, Anastaplo was a World War II veteran—he had navigated B-17 and B-29 bombers—and a top student at the University of Chicago Law School.

He had already passed the bar exam. He had begun talking to firms in the city. All that remained was a routine interview with two members of the Illinois Bar Association’s Committee on Character and Fitness. Anastaplo expected 15 minutes of pleasantries. Other applicants were waiting outside.

But the interview took an unexpected turn. After a few harmless questions, one of the lawyers asked Anastaplo if a member of the Communist Party should be eligible to practice law in Illinois. Anastaplo was surprised. “I should think so,” he said. But didn’t Communists believe in overthrowing the government? the lawyer asked. In the long colloquy that followed, Anastaplo, invoking George Washington and American political tradition, insisted that the right to revolt was “one of the most fundamental rights any people have.” The committee members were unconvinced. Finally the second one asked, “Are you a member of the Communist Party?”

Although this question was much in the air in the 1950s—earlier that year in West Virginia, Senator Joe McCarthy had brandished a list of Communists he claimed had infiltrated the State Department—no one seriously thought that Anastaplo was a Communist. Nor did anyone doubt his intellect, character, or patriotism. “If the mothers in Carterville have their way, all their boys will be like George,” Fred K. Lingle, one of his high-school teachers, had told the committee in a written statement. And yet Anastaplo had determined that, as a matter of principle, the committee had no right to ask about his political beliefs or affiliations. “I think it is an illegitimate question,” he replied.

Thus began a decade-long confrontation pitting an unknown but determined young Army reservist and Law School graduate against the Illinois Bar Association and the climate of fear and suspicion that then pervaded public life in the United States. Anastaplo never did become a lawyer. But the case made him famous as an example of resistance to communist witch-hunting and launched him on a long and prolific career as a scholar, law professor, and teacher of great books, a good-natured contrarian, gadfly, and independent thinker.

In the months and years that followed his first interview with the Committee on Character and Fitness, Anastaplo had many chances to change his mind and answer the question. He had plenty of encouragement to do so, including a warning from his Law School dean, Edward H. Levi, U-High’28, PhB’32, JD’35, that he was making a big mistake. But he refused—and kept on refusing. He declined, as one writer put it, “to follow the line of least resistance.” For its part, the Illinois Bar was no less intractable: it simply refused to admit him. Anastaplo sued. The two sides fought back and forth through ten years of hearings and rehearings, rulings and appeals, until the case landed before the Supreme Court in 1960.

By then Anastaplo had spent a decade practicing law, all on his own behalf. He made the oral argument himself. On April 24, 1961, the court ruled against him, upholding the Illinois Bar five to four. In a lengthy petition for rehearing that he had little hope would succeed, Anastaplo wrote, “It is highly probable that upon disposition of this Petition for Rehearing, petitioner will have practiced all the law he is ever going to.”

With that valedictory flourish, Anastaplo moved on. But although he had lost, neither he nor the case was forgotten, thanks primarily to Justice Black, whose dissent raised Anastaplo to something more than a legal footnote. Black had not taken Anastaplo seriously at first. Of his lawsuit, Black had confided to Associate Justice William Brennan, “This whole thing is a little silly on his part.” But recent cases had left Black worried about the fate of the First Amendment and of what he later called “that great heritage of freedom.” In Anastaplo he found freedom’s champion. “The very most that can fairly be said against Anastaplo’s position in this entire matter is that he took too much of the responsibility of preserving [this country’s] freedom upon himself,” Black wrote. He compared Anastaplo to great lawyers like Clarence Darrow and then, taking measure of the nation’s ills, decried “the present trend, not only in the legal profession but in almost every walk of life” in which “too many men are being driven to become government-fearing and time-serving because the Government is being permitted to strike out at those who are fearless enough to think as they please and say what they think.” He concluded with an exhortation that still resonates: “We must not be afraid to be free.” Black liked this dissent so much that he had parts of it read at his funeral in 1971. When Brennan, who voted with Black, read it, he told him, “You’ve immortalized Anastaplo.”

Anastaplo has been called many things, some worse than stubborn. Sidney Hook, the leftist New York intellectual turned anticommunist crusader, described him as “a very much confused young man—both philosophically and politically—with a large bump of self righteousness.” On the other hand, Leon Despres, PhB’27, JD’29, a Hyde Park alderman and one of Anastaplo’s most fervent admirers, dubbed him the “Socrates of Chicago.”

But Studs Terkel, PhB’32, JD’34, who interviewed Anastaplo twice on Chicago’s WFMT, may have hit closest to the truth when he described him simply as “one of those rare individuals who belongs to himself.” Anastaplo remains an unconventional figure, a lecturer in the Graham School’s Basic Program, a law professor at Loyola University of Chicago since 1981, and a writer of unusual range and productivity, with articles and books on subjects as diverse as the US Constitution, the Bhagavad Gita, and the lights at Wrigley Field. Shut out of the law, Anastaplo poured his energies into new channels, where, his friends say, he has proven himself as much his own man as he was before the Committee on Character and Fitness.

“To use a cliché, George really marches to his own drummer,” says Stanley Katz, an old friend and a professor at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. “I don’t know anybody of whom that is truer.”

Anastaplo inspires strong feelings. To a dwindling number of old friends and admirers—he has outlived not only his antagonists but also most of his old supporters—he is a heroic figure who stood up for liberty and decency at a dark moment in American history. At its 40th reunion, his Law School class gave him a bronze plaque that read “In admiration of a life devoted to high principle.” He has been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Later generations know Anastaplo mainly as a gifted teacher and writer who delights in expressing unpopular or idiosyncratic positions. His first book, a close reading of the First Amendment, holds that the amendment does not apply to the states, in contrast to the views of almost every other constitutional scholar. Once, at a ceremony honoring him for his defense of civil liberties, Anastaplo surprised the audience by arguing for the abolition of television. On a talk show, he defended Richard Nixon against Gore Vidal, asserting that Nixon’s Watergate transgressions were minor compared to the actions of some other presidents, such as Harry Truman.

“He has always behaved as some kind of gadfly,” Laurence Berns, AB’50, PhD’57, an old friend, said in a December 1982 Chicago magazine article written by Andrew Patner, X’81. “When the conventional opinion goes overboard in one direction, he tends to move in the other.”

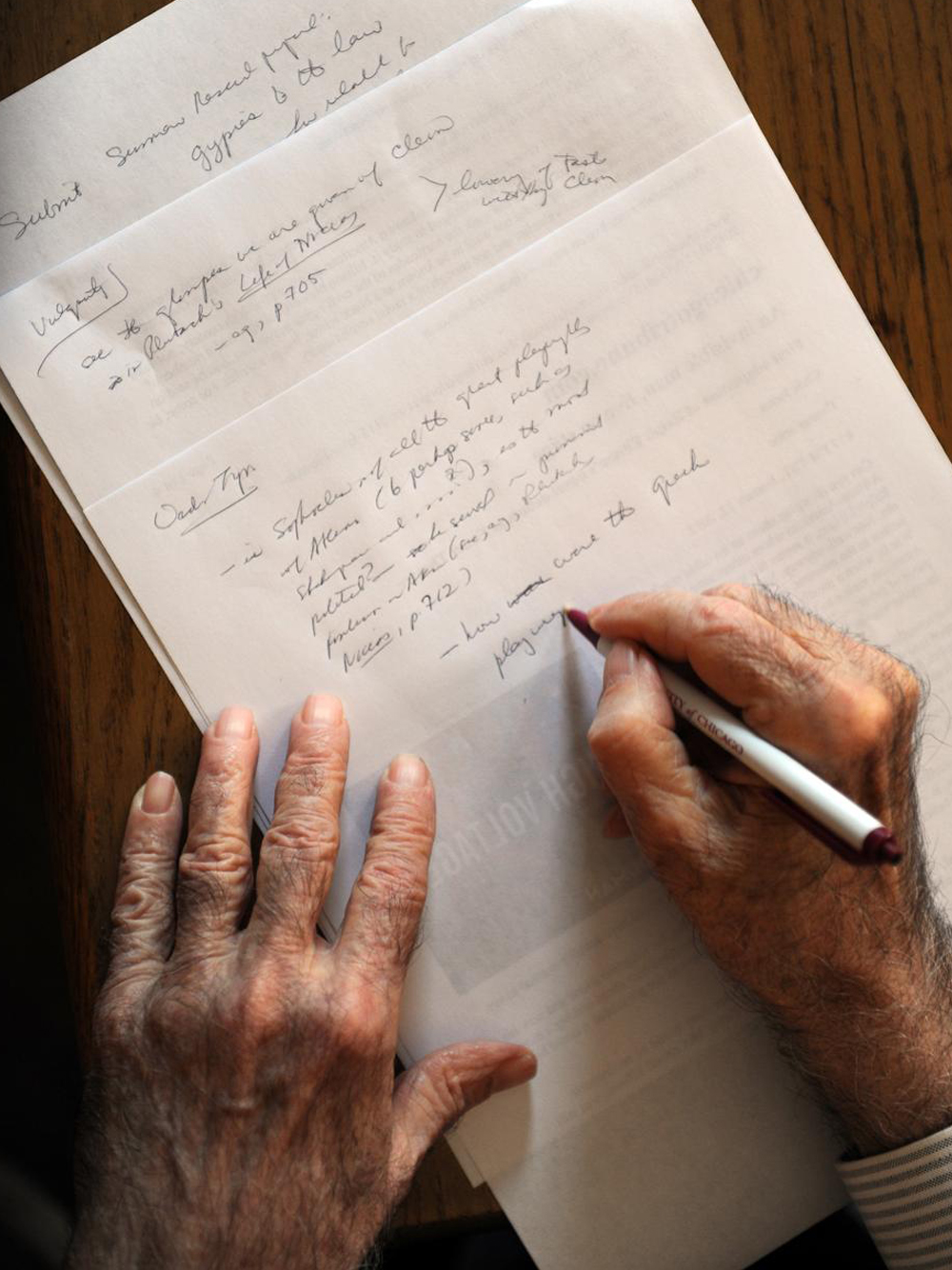

But Anastaplo is more than a gadfly. He is an intellectual omnivore, a generalist who respects few intellectual boundaries. In lectures, essays, and op-ed pieces, he often returns to favorite subjects, including the Constitution, the Greek classics, Shakespeare, and Lincoln. He comments frequently on contemporary issues involving questions of rights and liberties. Recently, for instance, he criticized the use of drones against terror suspects.

In fact Anastaplo writes about whatever interests him. He has published about 20 books, a dozen book-length law-review articles, and hundreds of essays. Many of his books treat aspects of the Constitution (including one on Lincoln and the Constitution), but they also explore literature (The Artist as Thinker: From Shakespeare to Joyce, Swallow Press, 1982), non-Western ideas (But Not Philosophy: Seven Introductions to Non-Western Thought, Lexington Books, 2002), religion (The Bible: Respectful Readings, Lexington Books, 2008), and other subjects far from his training in law and Western political philosophy. This variety is in part a consequence of teaching in the Basic Program, where, during a typical week last fall, he led discussions of Emerson, Plutarch, and Newton’s Principia, and where, he notes with a kind of pride, “I teach whatever other people don’t want to.”

It is also an expression of a lively curiosity and the freedom to follow it. Anastaplo frequently attends University lectures, panels, and colloquia—the Franke Institute for Wednesday lunch, a Physics colloquium on Thursdays—where, he laments, he is often the only layman in the room. As his friend Stanley Katz suggests, Anastaplo exemplifies an older intellectual ideal, one envisioned by Robert Hutchins’s university and Mortimer Adler’s Great Books of the Western World.

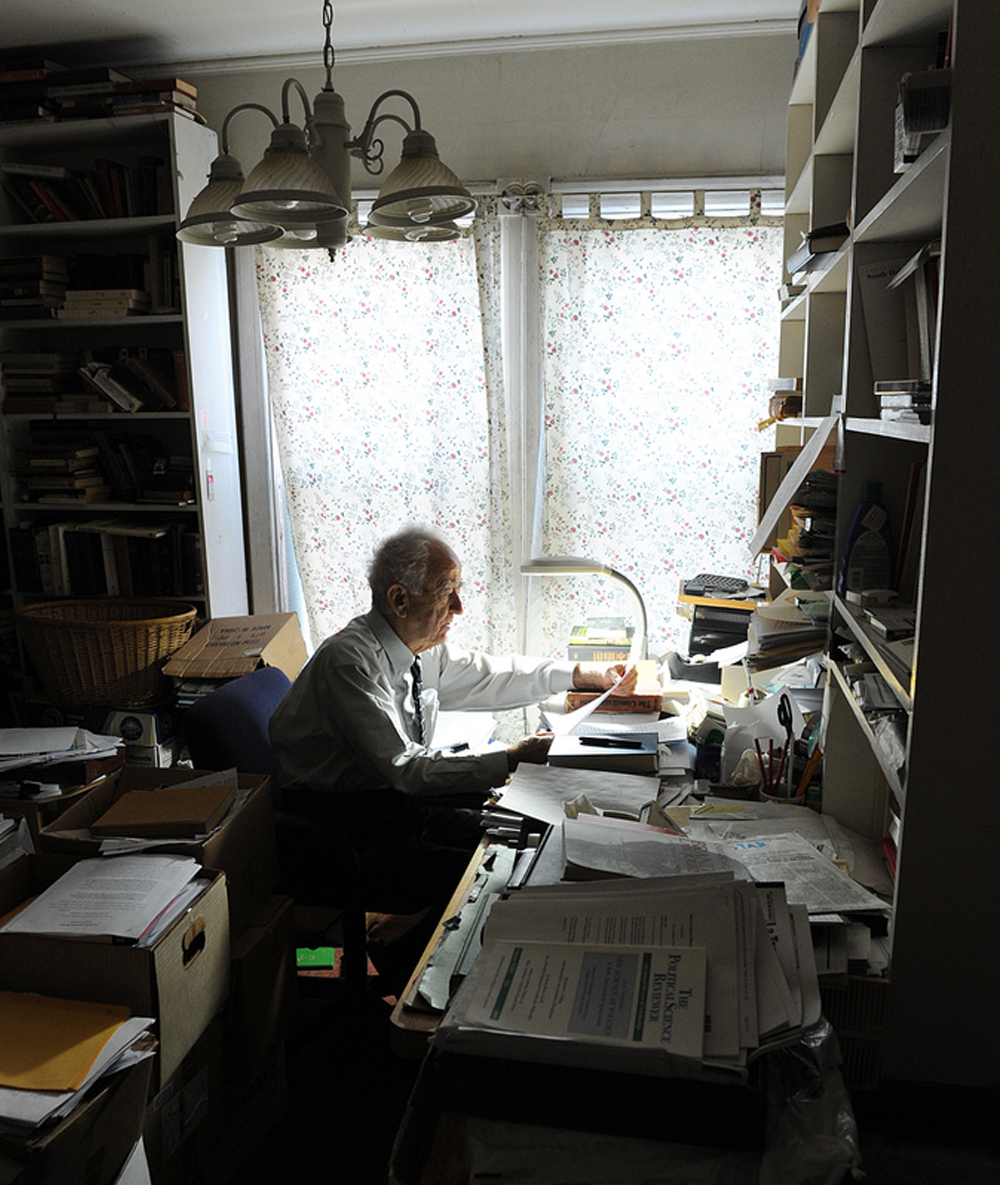

Friends have long marveled at his capacity for work. His eldest daughter, Helen Newlin, U-High’67, JD’75, CER’02, says that in winter he would rise and begin working as soon as the family’s modest wood frame house had cooled sufficiently to wake him. John Murley, a professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology in whose house Anastaplo stayed while a guest lecturer in the 1980s, remembers that his typewriter began clattering away at 5 a.m.

“I have always had the overwhelming feeling, when I’m with him, that I should get much more serious about my work,” says Murley.

In person Anastaplo is mild, courteous, and funny. He is a classicist at heart, with a deep faith in reason, moderation, and human goodness, and devoted to the search for enduring values. He is skeptical of modernity. He dislikes what he calls “value-free social sciences.” He is fascinated by the physical sciences but thinks their influence has been bad, chiding scientists for their “abandonment” of “common sense.” His 1961 petition to the Supreme Court included his own exhortation: “We must try to take seriously again the concern and conditions for virtue, nobility, and the life most fitting for man.”

“He’s a person who is profoundly conservative, with a small ‘c,’ ” says Katz. “He’s deeply committed to traditional values … that for him are more than intellectual. … The bar-admissions case was about that. This is simply a man for whom principle is everything.”

The bar case was not his only clash with authorities. In 1960 the Anastaplo family drove a Volkswagen microbus across Europe, one of many summer trips the family made. On a public square in Moscow, Anastaplo approached a group of British tourists handing out copies of an American magazine, attracting a crowd. He meant only to warn them they could get in trouble, but when the police showed up, he says, someone pointed him out, and he was arrested along with the others. The next day he was expelled. In 1968 Greece’s military rulers threw him out of the country for criticizing their regime. C. Hermann Pritchett, PhD'37, later quipped, “Any man who is kicked out of Russia, Greece, and the Illinois Bar can’t be all bad.”

As a teacher, Anastaplo has a talent for inducing thoughtfulness, says Laurence Nee, a tutor at St. John’s College in Sante Fe and a former student of Anastaplo. Once, Nee recalls, Anastaplo gave a talk on Constitution Day at the University of Dallas, a conservative Catholic institution where he taught for many years, flying down regularly from Chicago. Flag burning was in the news, and Anastaplo began by handing out photocopies of a canceled stamp bearing the image of a flag—in effect, a mutilated flag.

“His first motion isn’t to argue for or against a position,” says Nee, then a graduate student in Dallas. “It’s, ‘Have we thought about this?’”

Students like his obvious love of learning. He often scribbles notes in class, and he tries to approach each work afresh, using a clean text whenever he can. “He has a kind of boyishness to him still,” Nee says. “I think that’s part of his appeal. He enjoys learning. You can see the pleasure he takes in it.”

Monday and Tuesday mornings this past fall, Anastaplo taught at the Gleacher Center, then walked briskly up Michigan Avenue, a canvas tote in each hand, to teach jurisprudence and constitutional law at Loyola. He uses public transportation (or his feet) whenever possible, and until a few years ago he biked to classes downtown, pedaling an old three-speed up the lakeshore path.

Anastaplo’s freewheeling and often philosophical approach to the law is a welcome contrast to the “nuts and bolts” fare of other courses, says Rebecca Blabolil, a recent Loyola graduate who took Anastaplo’s class last fall. “His classes are an opportunity to think and exercise a part of your brain that has been dormant for the three years you’ve been here,” Blabolil says. During one week, for example, he discussed the Emancipation Proclamation, a new Supreme Court ruling concerning images on cigarette packs, and Civil War songs, which he described as a neglected window into sectional differences.

Anastaplo’s Law School classmates remember him as brilliant and witty, although quiet, even solitary. He was clearly not a typical law student. “He had his own ideas about how to spend his time,” says Abner Mikva, JD’51, who went on to become a congressman, federal judge, and adviser to President Clinton. Instead of joining the Law Review, a sure path to advancement, Anastaplo audited other courses at the University. When Dean Levi decreed that students wear coats and ties to class, Anastaplo continued to show up in jeans. When a lecture bored him, he would pull out a newspaper and read.

Few of his classmates, then, were surprised when Anastaplo defied the Committee on Character and Fitness, says Alexander Polikoff, AB’48, AM’50, JD’53, who later helped write a friend-of-the-court brief for him. “He was strong willed and stubborn when it came to constitutional principles.”

At the hearings Anastaplo was polite but confident. Transcripts suggest he was more than an intellectual match for his questioners. But he seems to have misjudged them. He arrived as if armed for a graduate seminar, laden with books, citing Jefferson, Locke, and English parliamentary rules, expecting to engage in real debate. To the lawyers on the committee, however, his arguments seem to have been mostly beside the point. The anxieties over communism in America, fanned by far right, anti–New Deal Republicans, were real, if misguided, and the lawyers could not easily discount them. In Chicago schoolteachers had been forced to take loyalty oaths. An Illinois legislative committee had been investigating communist sympathies among the faculties of Illinois universities, including the University of Chicago. Anastaplo’s talk about revolution was alarming.

“I had a feeling that George was not a communist in any shape or form,” said the late Edmund A. Stephan, who presided over a rehearing of Anastaplo’s case in 1958, in the Chicago magazine article. “But at that time, ‘communist’ meant somebody who would overthrow the government. It wasn’t something to be trifled with.”

A bigger issue for the lawyers—and a decisive one for the Supreme Court—was whether Anastaplo could get away with refusing to answer questions. His manner, as much as his arguments, exasperated some committee members. One told Patner he was “a smart aleck.”

“The big mistake, if it was a mistake, was in assuming that other people in other institutions had sense and good will, and they didn’t,” concludes Lawrence Friedman, AB’48, JD’51, LLM’53, a former classmate and today a professor of law at Stanford University. “It was an age of intolerance and moral panic. He was asking for trouble, and he got it. You don’t argue with George—‘Why are you doing this?’ It won’t do any good. I think it was admirable. He stood up for his principle. And he took the consequences.”

At the Law School, sentiment ran heavily against him. Students seem to have respected his principles but doubted the wisdom of his position.

“I think the majority felt that it was impractical,” says Ramsey Clark, AM’50, JD’51, a classmate and a former US attorney general. “It was kind of a quixotic gesture that might hurt the Law School a little bit. And I think some, and I shared this, felt some pain for what you might call a self-inflicted injury. But I admired him.”

A few Law School professors defended Anastaplo, but most did not. Several wrote a proposal, likely never adopted, to discourage other students from following his example. Levi, who went on to serve as University president and US attorney general, urged Anastaplo to reconsider.

“I thought Anastaplo’s position was ill-timed,” Levi told the New York Times in a 1975 profile published after he became attorney general. “I thought the big problem was the teacher-oath cases. I thought to raise the non-Communist oath issue with the Character and Fitness Committee was the wrong way to do it, and because of the timing of the thing he would lose and hurt himself, and he did. We were all trying to help him, whether he knows it or not.”

Indeed, Anastaplo felt betrayed. To this day he believes that if the Law School had stood up for him, the Illinois Bar would have backed down. For all his abilities, he says, Levi, then in his first year as dean, “was a timid man.” The faculty, too, “were fearful.” In his view, he was standing up to “hazing, harassment, whatever you want to call it.” His years as a flying officer in the Army Air Corps had helped to give him confidence. “I wasn’t going to be bullied.”

While the bar-admissions case was under way, Anastaplo worked at different jobs, including, briefly, driving a taxi. He also studied political philosophy in the Committee on Social Thought under Leo Strauss. He taught, first in the Basic Program and then, after earning his PhD, at Rosary College, the University of Dallas, and eventually, Loyola, often holding two or three positions at a time.

His relationship with the University has been complicated and a source of disappointment. With three degrees, Anastaplo is as much a creature of the institution as anybody. But he remains marginal. For a long time he hoped to secure a regular faculty position, and each time was rebuffed. In April 1975, after Levi had departed for Washington, Anastaplo loaded a shopping cart with manila envelopes and pushed it the mile from his house on Harper Avenue to the Faculty Exchange mail office. The envelopes contained samples of his writing, a bibliography listing some 300 publications, and a letter making “a quiet … appeal to the good sense of the University faculty.” They were addressed to acting president John T. Wilson, the provost, and the heads of schools, divisions, departments, and committees. He received a few replies but no offers. He never tried again.

Anastaplo did teach once at the Law School, in a not-for-credit course organized by Patner, then a law student. For many years he also met informally with graduate students in the University library. He recounts a separate occasion several decades ago when he was offered a course in the College and actually taught the first class—on the Declaration of Independence—only to have the offer withdrawn without explanation.

Anastaplo and his supporters say he was blacklisted because of the bar-admissions case and the opposition of his old dean, Edward Levi. He was too much of a troublemaker. Others offer different explanations. James Redfield, U-High’50, AB’54, PhD’61, a professor of classics and former master of the New Collegiate Division, recalls that he and Levi talked “more than once” about Anastaplo and that some professors recommended him. But Anastaplo lacked broad faculty support. The reason, Redfield suggests, was neither Levi nor the bar case but Anastaplo’s link to Leo Strauss. “There was generally a hostility toward Leo Strauss on the humanities faculty,” he says.

Katz believes that Anastaplo’s scholarship was simply too unconventional. “He has not respected any of the norms of academic discourse,” he says. “He’s turned that into a virtue, but he never would have gotten tenure at the University of Chicago like that.”

Still, Anastaplo has thrived in the academic hinterland, finding appreciative audiences at lesser known and often conservative institutions like the University of Dallas and publishing in obscure journals like the Oklahoma City University Law Review and the South Dakota Law Review. “The main thing is to write it the way I want it,” he says. “That’s what I’ve been able to do.”

Anastaplo has taken care that his writings do not languish in obscurity. “My model in self-advertisement is Don Quixote, who seems to have reckoned that if he (as an artist of knight-errantry) went to the trouble of doing useful things, others should benefit from learning about them,” he writes in an essay footnote. He collects many of his essays into books. In recent years friends have posted his writings on the Internet (at anastaplo.wordpress.com). And for most of his adult life Anastaplo has regularly sent packets of his writings to large numbers of friends and acquaintances. His children received packets when they were at college. So, in the last ten years of his life, did Hugo Black, who responded that he enjoyed them. “I have long thought and still believe that you have the capacity to make a highly useful citizen of this country,” he wrote in 1969.

Anastaplo’s work has attracted critical notice and often praise, but no large following. “George is prolific, original,” says Geoffrey Stone, JD’71, an expert on constitutional law and a Law School professor since 1973. “But in the world of legal scholars, he isn’t widely recognized.” An exasperated Dean Alfange Jr., now a professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts, noted in a 1974 review that Anastaplo would not extend First Amendment protection to artistic or literary expression: “Professor Anastaplo states that he knows of no one who agrees with his position on the First Amendment. It is unlikely that he will have to change that assessment as the result of this book.” Another writer praised Anastaplo’s “fervent and selfless moral vision, rooted in the classics of Western thought,” and called him a “rare intellectual: thought and learning are not for him the meaning of life, inducing a withdrawal into books, ideas, and ideological posturings; they give meaning to life, enabling one to live it actively and as perfectly as possible.”

At 86, Anastaplo maintains a busy schedule of teaching and writing. “That’s how you stay alive,” he says. He is in the middle of a projected ten-volume series called Reflections, each volume a collection of essays, or “constitutional sonnets,” as he calls them, on various topics. In the third volume, for example, titled Reflections on Life, Death, and the Constitution (University Press of Kentucky, 2009), he takes up Pericles’s funeral oration, assisted suicide, obliteration bombing, and “The Unseemly Fearfulness of Our Time.” In the meantime he is trying to publish a collection of essays on the aftermath of 9/11, as well as a book-length series of interviews he conducted a decade ago with a Holocaust survivor. He would like to write a book about Roma people and about Sophocles’s Oedipus Tyrannus, a work he considers “the greatest of our plays.”

Despite his full life, Anastaplo remains aggrieved by the bar-admissions case. He finds it ironic when people tell him they admire what he did. Last year, on the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision, he wrote, “If such people had expressed their admiration publicly in the 1950s, the Character Committee would probably have backed away from demands that were being made only of me.”

After anticommunist fervor cooled in the United States, friends and supporters tried several times to get Anastaplo finally admitted to the Illinois Bar. The Committee on Character and Fitness itself had a change of heart: in 1978 it voted 13 to 4 to certify him. But Anastaplo refused to reapply, and without his cooperation these efforts died. “George doesn’t want to let them off the hook,” says Katz.

Indeed, Anastaplo has done his part to keep the case alive. He has spoken about it occasionally and has chronicled it in immense detail, publishing not only most of the essential documents but also much correspondence and commentary about it afterward. “Frankly, I felt, and still do, that staying out on the terms I did was more instructive,” Anastaplo says. “I figured that, all in all, it was better to stay out.”

Was he too stubborn for his own good? Certainly Anastaplo sacrificed what might have been a lucrative law career. As a graduate of a leading law school, he might have found other opportunities open up to him as well. Many of his fellow students, including Mikva, Clark, Friedman, and Robert Bork, AB’48, JD’53, went on to distinguished careers in government and academia. From a practical point of view, says Clark, Anastaplo’s actions in 1950 were “catastrophic.”

But the practical point of view never was Anastaplo’s. In the end, he says, his case proved “liberating and even empowering.” It made him a symbol of principled resistance and set him on what he calls “my career as a naysayer.” More than that, losing the case gave him the freedom to “do what I want to do and publish what I want to.” Those who know him say they cannot imagine him doing anything differently.

“George is always at peace, as far as I can tell,” Clark says. “He was confident. The consequences, which he fully understood, were not a concern. He was determined to live a life of principle as far as he understood it. ... And that’s the type of life he’s lived.”