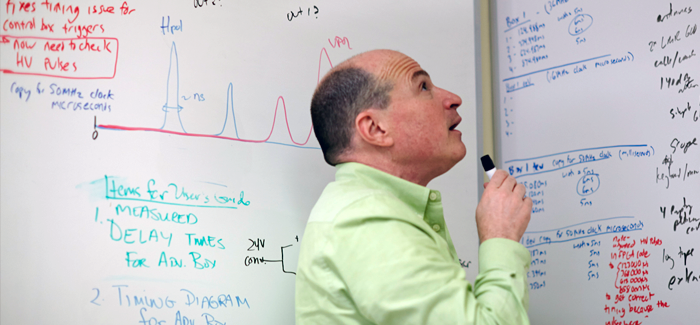

Physicist Saltzberg has gotten a big bang out of his television experience. (Photography by Anthony Chiappetta)

David Saltzberg, SM’91, PhD’94, keeps the research realistic on The Big Bang Theory.

Particle physicist David Saltzberg was in Antarctica in 2008, hunting for evidence of little-understood subatomic particles striking the ice continent. During his expedition, the UCLA physics and astronomy professor had another task that was almost as important to him: making sure scripts for the hit CBS sitcom The Big Bang Theory didn’t say sine when they meant cosine.

Saltzberg, SM’91, PhD’94, is the science consultant for Big Bang, which follows four brilliant, but often socially inept, Caltech researchers. Improbably, a show that finds comedy in electron transport and dark matter has become one of the most popular shows on television—nearly 19 million people watched its most recent season premiere. Ever since the 2006 pilot, it’s been Saltzberg’s job to keep the actors’ portrayal of university researchers believable. “Even though it’s a comedy,” Saltzberg says, “it’s a fairly accurate representation of what physicists do all day.”

Saltzberg’s own work focuses on neutrinos, particles with no electrical charge and almost no mass, which rarely interact with other matter. The high-energy neutrinos Saltzberg observes near the South Pole could shed light on the mysterious properties of cosmic rays, which seem to flout physicists’ theories.

Saltzberg has used the world’s most powerful particle accelerators, where subatomic particles are smashed together at nearly the speed of light for a glimpse of rarely seen building blocks of the universe. He conducted his doctoral research at Fermilab’s now-defunct Tevatron and currently works on CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland.

But instead of sifting through the aftereffects of an atomic collision inside an accelerator, Saltzberg looks for neutrinos made by cosmic rays in other galaxies that travel to Earth. Ice is almost transparent to radio waves, making Earth’s poles prime spots to use radio antennas and pick up any interactions between neutrinos and the ice. Saltzberg has been to Antarctica three times, sometimes sending telescopes in unmanned balloons to the outer reaches of the atmosphere to observe broad swaths of the ice. “Most people go in balloons to look up,” Saltzberg says, “and we’re the crazy people that point the telescope down.”

When he turns his professional attention to The Big Bang Theory, Saltzberg works with writers who keep up with prominent scientific news but often leave blanks in the script for him to fill in with science “gobbledygook.” Sometimes the writers will devise a key plot point and ask Saltzberg to flesh it out with realistic research.

In a recent episode, for example, the writers wanted main character Sheldon to make a significant discovery, but then realize he made a serious error. The achivement needed to be big enough to warrant Sheldon’s crowing, but not so large that it would appear unrealistic. Saltzberg gave the writers about a dozen suggestions, and they settled on Sheldon discovering a superheavy element. “It’s interesting and important, but it’s not an earthquake that would change the scientific world as you know it,” Saltzberg says.

In creating his formula, Sheldon misreads the units on a table, causing his result to be off by a factor of 10,000. That’s a common mistake in nuclear particle physics, according to Saltzberg, an Easter egg for experts in the field who may be watching. “There are probably dozens of people who got that joke,” Saltzberg deadpans.

Saltzberg also plans out the scientific scribblings on whiteboards scattered about the set. He tries to have the boards relate to scientific discoveries the characters are discussing, but if a scene is light on science, he’ll sneak in references to recent real-world discoveries.

The whiteboards have developed their own following, and Saltzberg occasionally hears from people questioning his calculations. Sometimes he plants a reference in tribute—as he did after the death of physicist John Wheeler, who coined the term “black hole”—or for members of the studio audience. A group of his graduate students attended a taping after taking an exam and Saltzberg adorned the whiteboard with solutions to the questions on their test.

Saltzberg attends the taping most weeks to chat with the writers and occasionally field questions on the fly. Watching the show live, he has come to realize that comedy writing is an empirical science. “You can argue, in theory, that your joke is funny and explain to everyone why your joke is funny, just like our theorists can explain to us why supersymmetry must be true,” Saltzberg says. “Every Tuesday night is an experiment where they decide whether a joke is funny.”

Since its premiere, Big Bang has been criticized for perpetuating negative stereotypes about scientists—that they can’t muster the courage to talk to the opposite sex and are social misfits. But Saltzberg says the characters are fundamentally likable and have evolved over the seven seasons; one has gotten married and others are dating.

Big Bang shows its characters outside their labs more often than not, but even brief looks at the work they do can only encourage more people to view research as a viable career, Saltzberg says, just like his passion for Isaac Asimov inspired him. “There are people out there that may have thought all of science ended with Newton or Maxwell.”

A particle physicist could spend an entire career going down dead ends, Saltzberg says, so increasing scientific literacy through the show could be as important as his research.

“My career’s not over yet—I don’t know if I’m going to stumble across a major discovery,” Saltzberg says. “So it may well be that the thing I have with the most lasting impact is the show.”