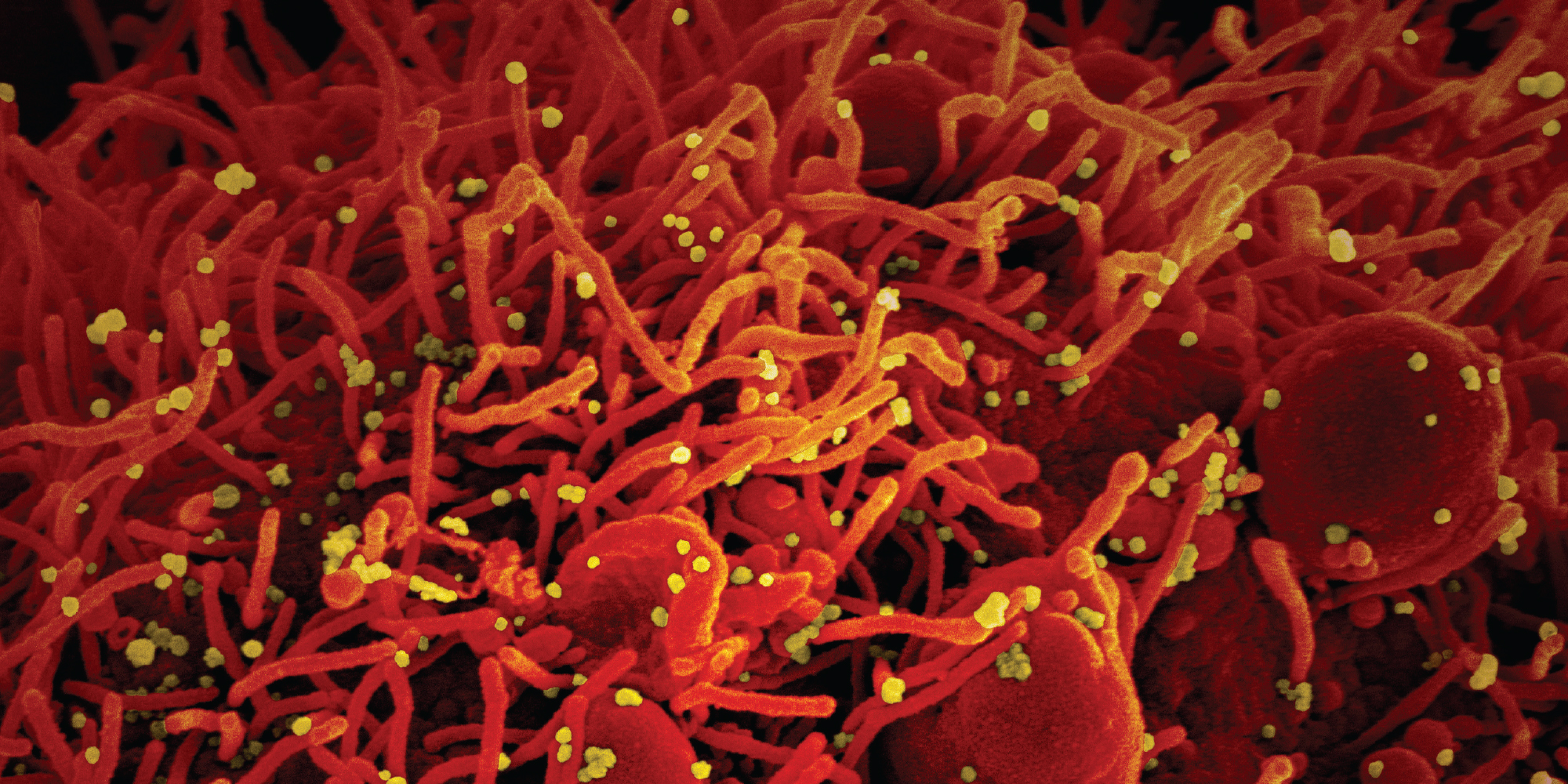

Colorized scanning electron microscope image of an apoptotic cell (red) infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (yellow). (NIAID)

While the mysterious new disease spread, UChicago Medicine researchers brought long-held expertise to a new common cause: helping COVID-19 patients.

In the very early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical researchers were inundated. Information about the virus came in an onrush. The pace made Mark Ratain think of Wayne Gretzky, whose father taught him to “skate to where the puck is going, not where it has been.”

Ratain, the Leon O. Jacobson Professor of Medicine, worked this spring to help identify the University’s most promising clinical trials to inform potential treatments for the mysterious viral infection. That meant divining, to the extent possible, where the puck was going. One problem with the metaphor: “This thing,” Ratain said, “is faster than ice hockey.”

Processes that normally take months or years had to be compressed into weeks or days, from conceiving research studies to getting the go-ahead from the Biological Sciences Division and University of Chicago Medicine Institutional Review Boards to securing patient consent. Ethical, medical, and logistical considerations—such as sealing consent forms in plastic to limit contagion from infected patients—had to be accounted for in each phase of ramping up clinical trials, even as researchers worked at a sprint.

Despite the obstacles and unknowns, the process sped forward. For example, the University reached an agreement with the pharmaceutical company Gilead to conduct a trial of its antiviral drug remdesivir, and within eight days doctors had started enrolling patients.

Ratain credited the “heroic efforts” of the BSD Institutional Review Board chief, professor of medicine Christopher Daugherty, in accelerating approvals. No corners could be cut. Providing patients with the best care remained the hospital’s primary imperative. But no time could be wasted either. Furthering potential COVID-19 treatments could make a global impact. The fast-tracked process, Ratain noted, contributed to the success of UChicago’s trial compared to other global remdesivir research.

“We got to trial very quickly and, therefore, did not have patients lingering in the ICU waiting for the remdesivir trial to open up,” he said during an online town hall in June reporting on UChicago Medicine’s COVID-19 research. “I think most other centers around the world were not as efficient in getting the trial started.” Like taking Tamiflu for seasonal flu, the earlier in their illnesses that patients receive the antiviral, the more effective it’s likely to be.

Daily infusions of remdesivir in 200 infected patients—half who required mechanical ventilation, half who did not but were hospitalized—produced encouraging outcomes. So encouraging, in fact, that when preliminary information about the participants’ swift and significant improvement was reported by the media, UChicago Medicine had to tamp down the enthusiasm, issuing an April 16 statement that said “drawing any conclusions at this point is premature and scientifically unsound.” By summer, the antiviral had become a staple of treatment for those hospitalized with COVID-19, hastening recovery for many. Gilead released data in July indicating a significant reduction in the death rate for hospitalized patients receiving the medication.

Other UChicago drug trials also showed hopeful results. The initial studies were small and not randomized. None came with promises of a COVID-19 cure close at hand. But the doctors were keen to nudge knowledge forward as the disease advanced around the globe. The unique scale and immediacy of the challenge rallied them to the cause.

“It is extraordinarily unusual to have a brand-new disease develop that impacts so many people,” professor of surgery J. Michael Millis said at the town hall. “The University of Chicago prides itself on developing lifelong learners, and when this new disease developed, it’s been amazing to watch how all of us have kicked it into high gear to learn as much as possible about this disease and initiated efforts to address it at all levels.”

A rush, in every sense.

Beyond adjusting their eyes to the blur of information about COVID-19, at times researchers also had to tune out the clamor over new developments. With the public anxious for answers and the media shining a bright light on research efforts, every potential step forward in drug and vaccine research was amplified. Political conflicts over potential treatments sprang up. In that environment, Ratain said, “it’s not like you can just put your head down and do your own work.”

Rheumatologist Reem Jan discovered that firsthand. The assistant professor of medicine set out to test the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 treatment. She came away with mixed results, her trial constrained in part because it was “very challenging to recruit patients with the massive attention that this drug has been getting.”

Like prejudiced jurors, many had formed opinions about hydroxychloroquine from news reports. President Donald Trump promoted the drug as a potential “miracle” coronavirus cure, saying he took it himself as a preventive measure after one of his personal valets tested positive for COVID-19. The president’s endorsement inspired some people to seek it out. Others resisted the medication for the same reason—the messenger.

Hydroxychloroquine is well understood and known to be safe when used, as it has been for decades, to treat malaria. It is most often prescribed in the United States for lupus and rheumatoid arthritis patients. Using knowledge from treating rheumatological conditions, Jan and her colleagues established “which patients should be excluded from the study and which side effects to look for” when testing the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19.

Some global studies had reported promising results. Others pointed to complications that could increase the risk of death. In the space of a week, the World Health Organization suspended and restarted its hydroxychloroquine research. At UChicago, amid that swirl of conflicting information, eight people enrolled in Jan’s trial. The researchers wanted to determine the optimal dosage of hydroxychloroquine and identify the subset of COVID-19 patients in which it could have the greatest impact. The amount typically prescribed to treat lupus and rheumatoid arthritis takes weeks to have a clinical effect. Those already seriously ill from the novel coronavirus infection could not wait that long for the drug to work.

Using three times the standard rheumatic dose on outpatients with moderate COVID-19 symptoms, Jan wondered, “Could we stop the disease from getting worse? Could we prevent these patients from being hospitalized?”

Yes and no, her small study suggested. Some patients showed almost immediate improvement. In others, COVID-19 progressed to the point of hospitalization despite the hydroxychloroquine intervention, although all eventually recovered.

“The good news is, most patients do seem to tolerate the drug very well and we haven’t seen any outright safety signals so far” in this small trial, Jan said at the June town hall. “The bad news is it’s very unclear as to whether the drug really works for this disease.”

The upticks of hope and plummeting expectations made for what Ratain called the hydroxychloroquine “roller coaster.” On June 15 the Food and Drug Administration revoked its emergency use authorization for the treatment of COVID-19 with the drug based on emerging studies showing it was unlikely to be effective and evidence of serious side effects in some patients.

Pankti Reid displayed two lung X-rays to the town hall audience. The first looked like one of those novelty skeleton T-shirts, a white rib cage outlined against a dark background. To a trained eye, the “translucent lung” in that image represented a healthy organ.

In the second, a fog appeared to have settled. Instead of clear black, the background was clouded and opaque, a telltale sign of “poor air exchange.”

The X-rays came from the same patient, before and after the onset of COVID-19.

Reid, a rheumatologist who specializes in autoimmune diseases, has expertise in overactive immune responses that create the kind of inflammation seen in the second image. When the immune system fails to distinguish between a threat and healthy human cells, the assistant professor of medicine said, it “can go into hyperdrive and wreak havoc.” That leads to the “cytokine storm” scenario, a factor that has caused serious illness or death in some coronavirus cases.

A small study from China published in early March showed that an anti-inflammatory drug called tocilizumab might help mitigate the effects of an excessive cytokine response. Normally used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, the medication brought swift relief from fever and reduced the need for oxygen in hospitalized patients, as well as improving indicators of inflammation in their bloodwork.

“It was revolutionary, really, in the COVID era to see this type of improvement, although in a small amount of patients,” Reid said. The significance and consistency of the benefits evident in that cohort “gave a lot of hope that this drug would be very helpful.”

Ratain is a pioneer in a field called interventional pharmacoeconomics, which focuses on maximizing drug effectiveness and availability, while reducing side effects and price. His influence helped establish the direction of UChicago Medicine’s tocilizumab trial.

Hematology and oncology fellow Garth Strohbehn, who also works with the nonprofit Value in Cancer Care Consortium toward lowering drug costs by identifying minimum dosages that provide maximum benefits, joined the study as well. Tocilizumab is expensive and in relatively limited supply, requiring careful management to bring beneficial outcomes to as many COVID-19 patients as possible.

Despite calling himself a “reluctant covid trialist” on his Twitter page, Strohbehn seemed like anything but to Reid, who noted he was the study’s lead author on the strength of his hard work and key insights. The team carefully deliberated over the optimal time to introduce tocilizumab in COVID-19, deciding to test the drug in a population with COVID-19 pneumonia who were hospitalized but not yet critically ill. This would help them determine if low doses could prevent the disease from advancing to the point of requiring intensive care or mechanical ventilation. As an anti-inflammatory—as opposed to an antiviral—the medication is not intended to fight the infection itself, but to limit the “hyperdrive” immune response. It inhibits a specific cytokine that can produce the debilitating inflammation visible in that cloudy chest X-ray. Echoing the Chinese study, participants in UChicago’s research showed swift improvement.

“In the 32 patients enrolled in our trial,” Reid said, “we saw promising results with general decrease of fever and lab markers of hyperinflammation improving in just 24 hours.”

The researchers are now studying tocilizumab in combination with antivirals like remdesivir, and whether the efficacy each drug has shown individually can be increased if the two are prescribed together.

The arsenal of medications that liver transplant patients need performs a kind of immuno-ballet—a course of treatment that restrains the body’s impulse to fight the new organ as a dangerous invader and, at the same time, prevents infections that could flourish under such immune suppression. Leflunomide maintains that delicate balance.

As it became clear that COVID-19 complications could arise from both the effects of the viral infection itself and the inflammation from an overactive immune response, Millis, a liver transplant specialist, got to thinking. He has extensive experience in China, having advised the country’s health ministry in developing a voluntary organ donation system, so he reached out to friends there: Was anybody using leflunomide to treat COVID-19 patients?

“It turns out that in March a group had done some in-vitro studies that showed that it was effective. And then another group had done a clinical trial of patients that had chronic viral positivity, and it had some nice effects,” Millis said. That information resolved him to design a study at UChicago Medicine.

The first step was determining which patients to test. With data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, Millis and colleagues established the characteristics of patients they wanted to test with leflunomide—those who had tested positive, were not hospitalized, and had risk factors such as age, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. Because infected people without those underlying issues had a much better chance of recovering without medical intervention, the researchers decided it would not be worth the risk of testing the leflunomide on them.

“So we identified this population that we thought would have a reasonable risk-benefit ratio to undergo a clinical trial—so-called equipoise,” Millis said. That “means that there’s a question out there that we don’t know the answer to, and there would be some risks, but there also would be potentially some benefit for patients.”

Like all the UChicago doctors involved in COVID-19 research, he was careful not to overstate the results of what was of necessity a small, nonrandomized study. But the patients in his leflunomide trial benefited. Their symptoms typically resolved within a week, faster than would otherwise be expected among that population.

“By day five, they are significantly improved, and by day seven, they feel great,” Millis said. “So that’s not the standard course. We think that that’s a little bit accelerated, which is what we would like to see.”

He believes leflunomide could be like a Tamiflu for COVID-19, given to outpatients with mild symptoms or to asymptomatic people who test positive, as well as a preventive medication for those who have come in contact with an infected person.

Millis’s interest in leflunomide traces back to a medical school mentor at the University of Tennessee, Jim Williams, who identified the compound’s combination of antiviral and immunosuppressive properties. Williams later moved to Rush Medical Center, and Millis recruited him to UChicago in the early 2000s. “He brought his expertise with this medication,” Millis said, “and the basic science people we had looked into it and found some other interesting facets.”

Long retired, Williams is unable to contribute to the latest research developments in treating COVID-19 with the drug, but Millis said, “we have enough critical mass and knowledge to move it forward in his honor.”

Could the misery that the novel coronavirus has visited upon the world be mitigated by taking vitamin D? There’s reason to believe it might help. Professor of medicine David Meltzer has undertaken research to help determine just how much.

As COVID-19 encroached on Chicago, Meltzer, LAB’82, AM’87, PhD’92, MD’93, the chief of hospital medicine, focused on preparing for an inevitable influx of patients. Meltzer also oversees the University’s Comprehensive Care Program, which works to strengthen patients’ relationships with their primary-care physicians to improve their health outcomes. At that time, the program’s staff was busy contacting their patients, phone call by personal phone call, to talk about the coronavirus threat and best practices for prevention.

In the midst of this metaphorical sandbagging for the coming storm, Meltzer received an email from a medical news service about vitamin D reducing respiratory tract infections.

Click.

“It reported the results of a meta-analysis showing an amazing 70 percent reduction in viral respiratory infections in people with vitamin D deficiency who were randomized to get vitamin D supplementation,” he said at the June town hall.

COVID-19 wasn’t mentioned in the email, and a Google search turned up no research into vitamin D’s impact on the new disease. But Meltzer remembered from medical school that coronaviruses often cause the type of infections the analysis evaluated. If such a safe, cheap, and widely available supplement could be shown to be beneficial against this novel threat, the impact could be significant.

“I also knew that about half of Americans and 70 percent of African Americans and Hispanics—which I’ll remind you is two-thirds of Chicago’s population—are vitamin D deficient,” Meltzer said. At the end of a long, cold winter, “I realized that we had the opportunity to study vitamin D deficiency and COVID at the U of C as these cases appear.”

First he had to get institutional review board approval to sift through thousands of electronic medical records to see whether a relationship existed between vitamin D deficiency and the likelihood of COVID-19 infection.

“What we found was yes, in fact, strikingly so,” Meltzer said. “Vitamin D deficient persons were 77 percent more likely to test positive for COVID than persons who weren’t vitamin D deficient. And this was true holding constant age, race, gender, and a whole series of comorbidities.”

People with a deficiency who had received vitamin D treatment, he found, did not have a higher risk of infection than those without a deficiency, an indication of such treatment’s protective potential—but only an indication. “I want to emphasize this is an association,” Meltzer said. “It doesn’t prove causation, so we knew we needed randomized trials. We’re trying to start three or four.”

Those include a study in collaboration with the UChicago Urban Labs involving first responders—police officers, firefighters, paramedics—and another with University health care workers. The latter will test moderate versus high doses. Taking greater amounts of vitamin D can cause side effects, and appropriate levels are not well established. The recommended daily allowance of 600 international units, Meltzer said, is based on the supplement’s benefits for bone health, not the immune system. Half an hour of midday sun provides 10,000 units, he noted, “so we know people evolved getting much, much more vitamin D than they’re getting today.”

For all the complications that COVID-19 research presented, the overall area of study was narrower than what Ratain typically encounters in his usual investigations into cancer drugs. There might be 1,000 in development at any given time.

“At least in COVID,” he said, “there’s a smaller space of things that one is thinking about.”

But the glut of information occupying that space—or trying to—clogged the pipeline. In June Strohbehn retweeted a photo of hikers queued up on Mount Everest with the caption: “#Covid_19 manuscripts waiting for editorial review at medical journals.”

UChicago Medicine’s contributions to that crowded field generated real, if incremental, progress in treating the disease. As hospital operations temporarily slowed to ensure capacity for patients with COVID-19, these doctors did not go idle.

“When you basically tell all these people, ‘You’ve got to stop,’” Millis said, “well, their minds don’t stop.”

If anything, when presented with the opportunity to help quell a pandemic, they only went faster.

Jason Kelly is associate editor of Notre Dame Magazine.