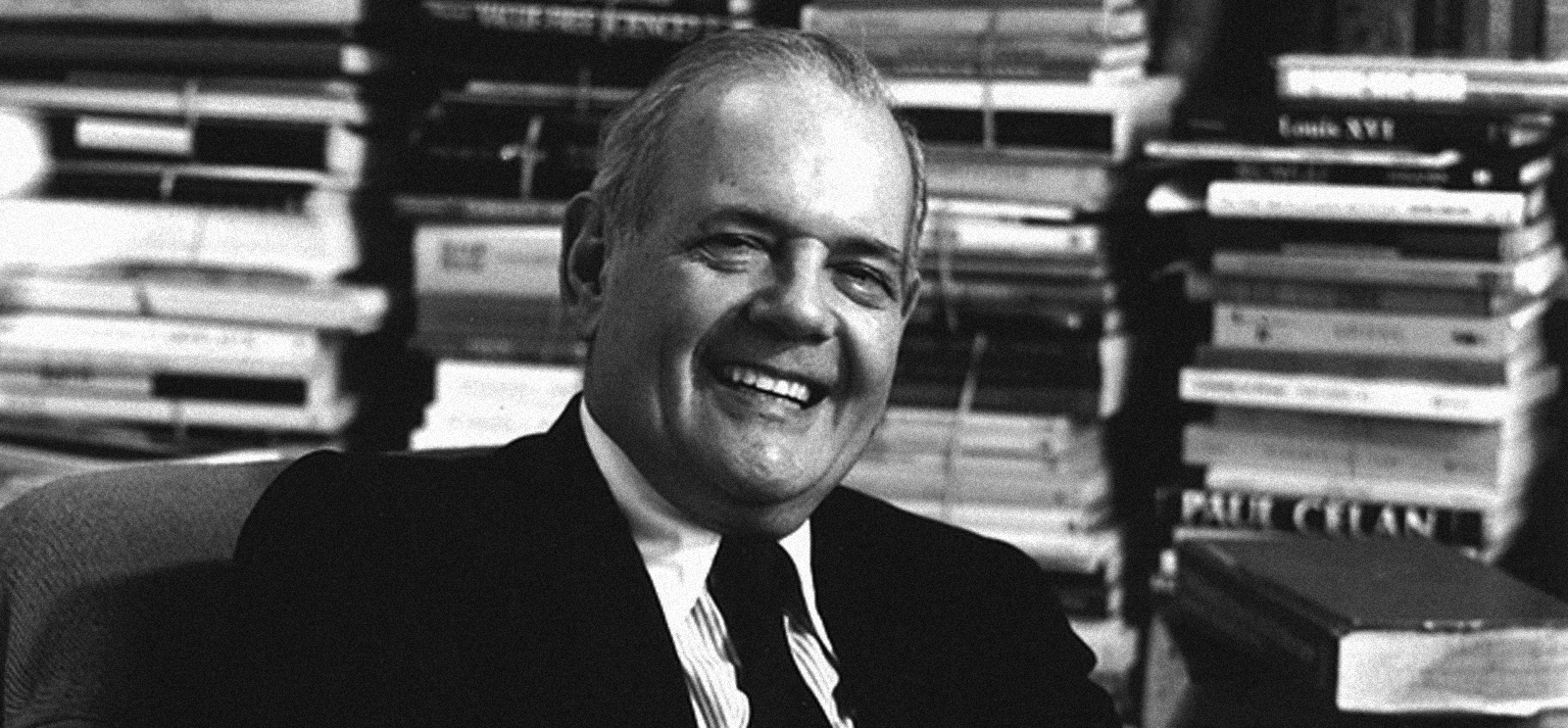

Silvers works in his office. (Photo courtesy Robert Silvers)

For 50 years Robert Silvers, AB’47, has expertly paired writers and subjects at the New York Review of Books.

To hear Robert Silvers tell it, the story of his journey—from working on a Long Island chicken farm to cultivating one of America’s most prestigious publications—might seem unremarkable. On a spring Tuesday afternoon, Silvers, AB’47, momentarily relaxes on a plush blue couch and gazes off into the West Village loft that houses the New York Review of Books, the paper he has edited for nearly half a century. To his right, neatly organized, are the hundreds of books that make up the complete library of Barbara Epstein, his longtime coeditor, who died in 2006. In front of him lies open office space, broken up by islands of bookshelves and streams of midday sunlight.

Silvers’s voice is giddy as he remembers the three years he spent in Hyde Park, which began in 1945 at age 15. Silvers took Social Sciences II from Daniel Bell, a forefather of postindustrialism. He learned Freud from the Pulitzer Prize winner Sebastian de Grazia, AB’44, PhD’48. Anthropologist Robert Redfield, U-High’15, PhB’20, JD’21, PhD’28, was his professor for Social Sciences III, and he learned physics from Enrico Fermi himself. His classmates included not only burgeoning young intellectuals like George Steiner, AB’48, and Robert Bork, AB’48, JD’53, but also bomber pilots and GIs attempting, through literature and introspection, to understand the horrors they had witnessed on the battlefields of Europe and in the fiery jungles of the Pacific. The quads were active both artistically and politically. Meetings were held by Trotskyites and World Federalists. As Silvers recalls, “There was a spirit on the campus at that time of extraordinary openness, experimentation,” an atmosphere that incubated and inspired his appetite for ideas.

After graduation, and without an inner calling for any specific vocation, Silvers briefly attended law school at Yale. When he received an invitation from Connecticut governor Chester Bowles—whom he’d met in Chicago as an undergraduate—to work on his 1950 reelection campaign effort, it would become one of many opportunities in Silvers’s life that he could not pass up. Although Bowles lost the race, Silvers served for several months as a press secretary before he was drafted at the onset of the Korean War by the Army and sent to Paris to do intelligence work at the NATO military headquarters for the Supreme Allied Commander.

There Silvers fell into the industry he would later help to define. With enough freedom to both wander the city and study, Silvers learned French and took classes at the Sorbonne and the Paris Institute of Political Studies. Meanwhile, two friends from Chicago who were running a small publishing house asked Silvers if he could scout for books worth translating and selling to an American readership. In doing so, he met George Plimpton, who offered him another irresistible opportunity: “When I was going to get out of the Army,” Silvers says, “we made a kind of deal that I would join the Paris Review,” which he did in 1954.

From assigning stories to reshaping what had already been submitted, editing was a natural fit for Silvers. It wasn’t long before Harper’s magazine proposed a generous relocation package to return to New York. Silvers had spent six “marvelous” years in Paris. He was in love with the city, but this was another opportunity he simply could not refuse. Besides, as he once told his former assistant and longtime New York Review of Books writer, Mark Danner, “If you’re an editor, you should probably have a crack at editing in your own language, in your own country, rather than being an expatriate forever. So, I thought I would try it.”

In New York Silvers began preparing for a special issue of Harper’s on the general state of writing in America. He tapped writer Elizabeth Hardwick, who produced her famous essay “The Decline of Book Reviewing,” an incendiary diatribe in which she took the establishment review culture to task for being too “sweet” and “bland.” The October 1959 article attracted widespread attention and indignation, and it created, as Silvers recalls, “the possibility of a new book review, but everyone thought it was impossible because there would be no advertising.”

Three years later a newspaper strike opened the door. At a small dinner party that winter, Jason Epstein—the Random House editor extraordinaire who first sensed the commercial potential of paperbacks and went on to publish American classics and to create a precursor to online bookselling—suggested that, because of the strike, there had never been a more opportune moment to found a revolutionary book review. With the New York Times, the Herald Tribune, and the Saturday Review shuttered, publishing houses were desperate for a place to advertise their books. By dessert, Epstein; his wife, Barbara; poet Robert Lowell; and Hardwick had conceived the New York Review of Books. Their choice to coedit the Review with Barbara was the young Harper’s editor people had been chattering about: Robert Silvers.

Because no one expected Silvers to accept the position, the founders were surprised when “he came over in a minute and just pitched right in,” Jason Epstein recalls. “He really was born for this job … and was enormously confident in every respect, not just as an editor but putting things together and even setting up furniture.” Within three years the Review was profitable and had an office in the Fisk Building on West 57th Street, right off Central Park.

With a corporate structure that allowed Silvers and Barbara Epstein complete editorial control, the Review, from its first issue, exactly reflected the interests and tastes of its editors. Both writers and readers quickly took notice of one of Silvers’s patent talents. Like a chemist pairing ingredients to induce a specific reaction, Silvers has built his career matching the right author and subject, in hopes of generating an exciting and illuminating result. “Part of the genius of Silvers is that he puts a writer together with material that even the writer might not have thought was appropriate,” says Daniel Mendelsohn, a critic who has written for the Review for more than a decade.

When Silvers asked Harper’s for a leave of absence to start the Review, they said yes, convinced that Silvers would be “back in a month.” It’s been more than 50 years, and the Review now boasts a circulation of 135,000. The renewal rate is among the highest of any national publication, and because it is independently owned, Silvers has never had to sacrifice the Review’s founding principles. He has become perhaps the most lionized figure in the industry, and also one of the most private and fabled. His work ethic is legendary. Although he and his longtime companion, Grace, Countess of Dudley, are part of the city’s social whirl, Silvers often can be reached at his office after midnight. When asked why he logs so many hours, he responds with a perplexed look, as if the answer should be obvious.

“It’s a question of an opportunity to find brilliant, interesting writers and give them a chance to reach an audience that will appreciate them. I find enormous pleasure in doing that.” And, he adds, it’s “often not at all easy.”

Milestones

1945 At age 15, Silvers enrolls at the University.

1954 George Plimpton, whom Silvers had met while in the Army, makes good on a promise and hires Silvers at the Paris Review.

1958 After moving to New York and Harper’s, Silvers enlists Elizabeth Hardwick to write “The Decline of Book Reviewing.”

1963 Silvers becomes founding coeditor, with Barbara Epstein, of the New York Review of Books.

2006 Epstein dies, and Silvers carries on, adding her workload to his own.

2012 Silvers earns lifetime achievement awards from the National Book Critics Circle and the

Paris Review.

Philip Marino is an assistant editor with Liveright Publishing, a division of W. W. Norton & Company. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.