(Photography by Chris Kirzeder)

Onward and upward with the arts: a glimpse into the inner workings of the towering new facility south of the Midway.

The Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts is at once a classroom building, performance hall, exhibit gallery, rehearsal space, and studio for almost every kind of art. As the center prepared for its official opening in October, the Magazine spoke to some of the people who make the place sing, dance, and fly.

Box-office manager Travis Ray tends to every audience need between the door and the curtain.

Crowd pleaser

It’s hard to decide what’s more boyish about Travis Ray, his appearance or his enthusiasm. The 27-year-old UChicago Arts box-office manager could easily be mistaken for one of the 20 students who work for him. In fact, he has been.

Once, while he was giving a tour of the Logan Center, a woman asked Ray what year he was. “I thought, ‘What year?’” he says. “I was taken aback.” He pauses as the twinkle in his eye expands into a toothy expression of appreciation. “But I thought it was a wonderful compliment.”

Not even his penchant for bow ties—in muted gray plaid or maroon bearing the logo of his home state alma mater, the University of Alabama, to name just two of “a lot, in various colors”—would prevent a vigilant bouncer from checking his ID. And he is young enough that he learned how to tie them from instructional videos on YouTube.

His personality is as vivid as his favorite fashion accessory. At a summer photo shoot for the Magazine, Ray vamped with playful abandon, offering not just his time in the midst of his Logan Center grand-opening preparations but also his spirit. It was easy to see why a talent agent plucked him from a junior-high mall fashion show to appear on a Chick-fil-A billboard. The performer in him is apparent even in a still photograph.

But Ray has always had behind-the-scenes ambitions as well. Even as he pursued undergraduate and master’s degrees in performance as an actor and dancer at Alabama State and the University of Nebraska, “I’ve always known that I wanted to one day own my own theater company.”

In 2009 Ray embarked on a University of Alabama MFA program in theater management, which he completed last year. As a student, he spent two years as box-office and marketing manager for the school’s theater department.

That experience gave him insight into complications—unseen (fingers crossed) by the audience—that go beyond designing seating charts and printing tickets. Different performances have different needs, a reality multiplied at the Logan Center, which abounds with spaces and groups. “One group might want to use Row A, whereas another may not because they might use Row A for an orchestra pit, or for special guests, or not at all because of sight-line issues. So those are some things that could alter a seating chart,” Ray says, lingering for a moment over implied ellipses before adding, “and could mess up your count.”

As his job is structured, in part shaped by him as the first to occupy it, it goes beyond ticket sales and seat configurations. “My idea for the box office was that it have almost a concierge feel,” Ray says, with he and his staff tending to whatever needs might arise for audience members between the door and the curtain. “Everything,” he says, including the café, this summer still a construction site as Ray anxiously awaited its addition to the building’s ambience.

On show nights, he will be found hustling around the building wherever his walkie-talkie or patrons summon him. He can’t wait. Appearances aside, Ray really does resemble an ambitious and enthusiastic first-year in many ways. New to the University and the city, he’s at once entranced and challenged by the offer he accepted in the spring.

Add the curtain-rising buzz around the Logan Center and, for Ray, every day feels like opening night.—Jason Kelly

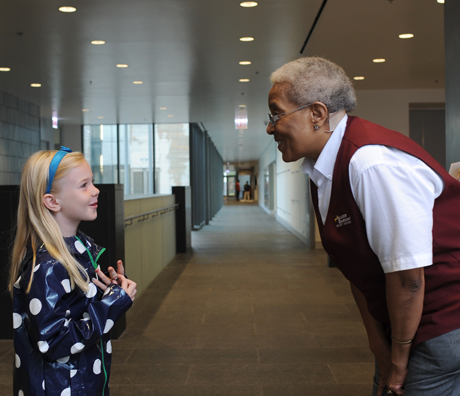

Security officer Brenda Johnson is always ready with a “mother hug,” but she has a mischievous side too.

Jests with guests

The elevators in the Logan Center have security cameras. And at any moment, Brenda Johnson may be watching. She’s the lead security officer at the front desk, a position that also makes her the building’s de facto greeter—and occasional practical joker.

Take the day when the elevator cameras malfunctioned and the screens at her desk stayed black. A young woman stepped out of the elevator onto the first floor and Johnson yelled, “Why did you do that? In the elevator? Why did you do that? I can see you!”

“What? Do what?” the young woman said, confounded.

A few moments later, Johnson let her in on the joke. “They know I’m jiving with them,” she laughs, recounting the prank.

It’s part of her charm. Johnson, 61, is considered the building’s house mom, a role she has performed for years to her four children, ten grandchildren, and five (soon to be six) great-grandchildren. She is always ready with a “mother hug.”

But beware: as the elevator story shows, she has a wicked side too.

Her occasional desk buddy Josh Babcock, ’13, a student employee, chimes in to help explain her double nature: “You’re friendly, you hear about everything everyone is doing, and you have snacks in your drawer. And you give everybody a hard time.” She can hardly suppress a widening grin. “Do I really?” she asks in faux surprise.

Along with her more informal greeting duties, Johnson supervises both main entrances to the building, the loading dock, and all who come in and out. She also issues and tracks radios and keys used by building staff, and keeps a precise log of the day’s activities.

She’s really in it, though, for the people. Johnson spent almost three decades as an office associate for the state of Illinois, retiring in 2006. But after only a couple years away from work, she couldn’t stand the quiet. She returned as a security guard at Chapin Hall, a few blocks east of Logan. “I didn’t realize how much I missed people until I came back.” Although she enjoyed her time at the policy research center, she welcomed the move to Logan. “Chapin was very quiet,” she says. “This is more exciting.”

Johnson interrupts the interview to track down a custodian who is being paged—cell-phone coverage is sometimes better than walkie-talkie reception at the Logan Center, and Johnson has resorted to texting. “This is part of my job too,” she explains, “tracking everybody down.” She looks down through the glasses on the bridge of her nose at the cell phone she holds as if it’s a hunk of uranium. “My kids are much faster at this than I am. In fact, they had to teach me how to do it—my grandchildren had to teach me.”

Moments later a Logan regular steps through the north entrance and passes Johnson’s desk. She perks up: “Good morning! How are you? Happy Friday!”—Colin Bradley, ’14

The high schoolers in Catherine Sullivan’s (center) summer film class were cast and crew of their own sci-fi movie.

Action sequence

Standing so close they could have locked arms, the space captain, the evil space pirate, and a menacing robot in aviator goggles glowered at each other in the Logan Center’s sixth-floor stairwell and tried hard not to laugh.

“Fight it. Fight it. Keep fighting it,” visual-arts assistant professor Catherine Sullivan coached as the camera rolled, held by a 16-year-old girl in sunglasses and a black kimono. The three boys contorted their faces, their grimaces slipping, until finally they collapsed into peals of laughter. “Cut!” Sullivan said, not quite stifling a chuckle. “OK. I think we got a few seconds of it.”

The group’s science-fiction film, as yet untitled, was under way.

On Saturday mornings this past summer, while the rest of the Logan Center mostly slumbered, Sullivan and a class of local high-school students met in the basement computer lab, where she taught them the basics of film editing and shooting, starting with how to turn on a video camera—many of the students had never held one before. Later she showed them how to frame actors and scenes, how to add effects with digital software, how to forge together tiny moments of action and dialogue and music to construct characters, plots, a finished movie. The summer’s final project was a science-fiction fantasy conceived, shot, and edited by the students and then screened for their friends and families at Logan. “I’d like to make this an ongoing thing—I’d like to do it every summer,” says Sullivan, a film artist whose video installation Inaugurals was the first exhibit to open in the building’s gallery this past March. Sullivan co-organized the film class with a Kenwood nonprofit called Faithful Few. The group’s president and founder, Denard Jacox, whose day job is at the Chicago Booth copy center, sat in on every class, corralling the students and working alongside them. “This is how we get them to explore their talents,” he said. “Classes like this.”

On the last Saturday in July, the students worked first in the computer lab, cutting and splicing fight scenes from several kung-fu movies (plus a Clint Eastwood Western) to produce what Sullivan called the “ultimate kung-fu cut,” a three-minute action sequence creating the illusion that all the fights were happening at once. Leaning over one student’s monitor amid intermittent hi-yahs and the sound of thrown punches, Sullivan said, “Good. Now, see if you can make it even more chaotic.”

After a midmorning snack, they got started on their own movie. Students chose among bits of costumes Sullivan brought from home—a pilot’s hat and epaulets, plastic laurels, a plague doctor’s mask, half a clown suit, a green feathered cap—and then, chattering excitedly, headed upstairs with their cameras and tripods. By the time they stepped off the elevator at the sixth floor, a cast of characters had emerged: the space captain, the pirate, the robot, a “ghetto geisha,” a caped masquerader, and Jacox as “Robin in the Hood.”

For the next hour or so, they shot as many scenes as they could, heeding Sullivan’s admonishments about light and background, camera angles and composition. A couple of students fanned out across the building in search of “texture”: abstract close-ups and zooms of architectural details and outside scenery. The class shot a scene in which two characters seemed to be communicating telepathically (“Look at him like, ‘Tell me something! Tell me something!’” Sullivan directed), and then the glowering stare down that dissolved into laughter. After that, all but exhausted, the film crew went to work on the day’s last scene, a chase down the stairs. The three boys’ wild footfalls echoed off the tile walls and tall windows as two of their classmates peered into viewfinders. “Roll cameras,” Sullivan called out. “And … action!”—Lydialyle Gibson

David Wolf connects artists with their technical needs.

Media personality

David Wolf’s title is Logan Center associate director of arts technology and digital media, “which,” he notes, “is quite long.” Then again, to call Wolf, AB’00, MFA’05, something like “keeper of the equipment cage” wouldn’t be comprehensive enough. There’s no easy way to sum up what happens at the Logan Center, as Wolf’s job illustrates.

Technically, he manages the equipment and facilities available to students, faculty, and staff for multimedia projects—cameras; sound and lighting equipment; a computer lab; a production studio; editing suites for video, film, and animation (again, not a complete list). Wolf’s position also places him at an intersection of artistic mediums and academic departments—where, according to one of the Logan Center’s operating principles, the chocolate and peanut butter will collide. “We have an ambitious idea,” Wolf says, “that musicians will talk to video artists and painters will talk to actors and come up with new and interesting art forms as a result.”

Exactly how that will happen, they don’t know yet. “We’re still at the point of learning how to live together,” he says. Logan Center staff members, Wolf says, “take it really seriously to sort of jump-start that activity and do our best to create environments where people come together.” From his perspective, the building’s environment appears to be producing an artistic climate change on campus. The diverse departments involved, the inspiration from unforeseen interactions—“all of that,” Wolf says, “puts heat around the idea of the central nature of art making to this campus.”

It was central enough to attract and retain Wolf, who was involved with University Theater, Doc Films, Fire Escape Films, and WHPK as an undergrad. A sculptor with a master’s in visual arts, Wolf worked in DOVA’s Midway Studios office from 2005 until he joined the Logan Center late last year.

The digital media center that Wolf oversees provides equipment for everyone to the extent its inventory allows. Before Logan opened, individuals or student groups might have gone begging for permission to use a department’s gear, “and it would’ve probably been given grudgingly,” Wolf says. “Now we’re really set up to do that kind of thing.”

Among his challenges now—which also include managing technology needs for the many events already held at the Logan Center—is making sure the campus community takes advantage of all the building offers. “There are students who knew about this building going up a long time ago and have been waiting with bated breath for us to open, and they’re going to squeeze every last drop of resource that they can out of here before they graduate, which is great,” Wolf says. “Our challenge is to make sure that we can help those students, but also help as many students as we can.”

The digital media center is like a high-tech library, open to everyone with a UChicago ID, although checking out gear requires an orientation in the equipment-cage policies. Accessing higher-end equipment requires additional specialized training.

On a summer afternoon, a student works the equipment-cage desk on Logan Center’s lower level, sitting in front of a wall of coiled cables that looks like an aisle in a hardware store. Down the hall are the computer lab, production studio, and editing suites. Artists working on high-tech projects will find tools that might have been inaccessible before, if they were available at all.

Those tools are part of the Logan Center’s larger mission to be a central location that turns a thriving campus arts scene into a hive mind of innovation. “It’s huge. It’s going to change it in ways we don’t even know about,” Wolf says. He recalls the spaces that served his artistic ambitions well as a student—among them Ida Noyes, the Reynolds Club, Midway Studios—many of which will continue to be creative hubs, but none gathering so much energy under a single roof. “Never,” he says, “at the scale we’re doing here.”—Jason Kelly

To Lasana (in black), stories are like communities.

Narrative ties

When a story wants to be told, it wants to be told,” explains one student, Dorothy, before she begins hers. “So it kept pushing me. The story brought me here this morning.”

Dorothy is one of several adult students sharing their journeys on the final day of the Logan Center’s oral storytelling class. Everyone is required to spin one last yarn, and hers is about Melissa, “who ate herself today”—a girl addicted to food. The others—some recounted previously and some conjured this morning—run the gamut from folk tales to fables to true accounts. A few of the students in the tight-knit class are new to the game; others, including instructor Emily Hooper Lansana, are veterans.

For six weeks this past July and August, Lansana taught Storytelling, a free class for people 40 and older from Hyde Park and surrounding neighborhoods. “Storytelling is really important because it allows people to recognize their strengths,” Lansana says, “and to build meaningful connections with others.” She has led similar classes at community centers, schools, and universities; she and fellow storyteller Glenda Zahra Baker, collectively known as In the Spirit, have performed at festivals nationwide.

Although she’s hoping to teach more classes, Lansana's official position is community-partnerships manager for the Logan Center and the University’s Arts and Public Life initiative. She works to build programs that will help the University and its neighbors create sustainable partnerships. Recent initiatives include an open exhibition, Local Metrics: Majeed, Mooses, Myrie, in the Logan gallery and a community youth arts showcase. The Logan Center “was primarily designed for use by faculty and students and the arts programs,” Lansana says, but “it’s also an important hope that it’ll be a community asset.”

In the final class, Lansana is the last to share. The class has heard stories about a mischievous slave, a greedy spider, and a hoodwinking monkey. There was one about finding love on the Internet and another about finding a long-lost mother. “All right, so here’s the last story,” Lansana says. “This is a story that’s adapted from a Hebrew story. The story says that there was this village. In this village there was a little boy who was always in trouble.”

As a teacher, Lansana exudes a deliberate, calming presence. But when she’s telling a story, her voice jolts the room into unwavering attention. As she relates the desperation of the young troublemaker’s parents, who take him to a village elder to seek solutions for his wayward behavior, the narrative hurtles forward behind the self-assurance of her delivery.

In time, the boy grows to be a great man and becomes a teacher. “And one day, when he was surrounded with students, they said to him, ‘How did you learn to be such a wonderful teacher?’” Lansana pauses, looking around the room. “He said, ‘I learned everything that I do here from listening to the beating of the elder’s heart.’” A few students gasp at the tale’s revelation. “May we have the courage and peace to take the time to look into each other’s eyes, and hold each other’s hands, and to listen to the beat of our hearts.” Applause erupts, and Lansana beams.—Emily Wang, ’14

“I was missing the arts,” says Logan Center operations director Greg Redenius.

Sound operator

In one of the Logan Center’s three music-ensemble rehearsal rooms waits a fully assembled, ready-to-play drum set. It seems like the perfect place for an overworked, self-described “basement drummer” to take a load off for a few minutes. But with the Logan Center preparing for the October 11 grand opening, associate director of operations Greg Redenius is sticking to a different beat. “I haven’t been able to take advantage of it as much as I’d hoped to,” he says of the drum set. “Maybe when things slow down here a little bit.”

Redenius admits the chances of a slowdown are slim. In 1985, while pursuing an arts-management major at Columbia College, Redenius started working as a stage manager for the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra. After graduating he worked in several facilities and operations roles during 15 years with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, before joining Chicago Booth in 2004 as senior associate director of facilities services for the then brand-new Harper Center. But, he explains as he glances at a framed digital rendering of the Harper Center signed by his former colleagues and presented as a parting gift, “I was missing the arts.” When he learned of the development of a new center for the arts, he was eager to get involved in the planning and execution.

Now Redenius is the person whom, if his job is done correctly, Logan patrons and visitors should never have to think about. He is the grease in the hinges. He grants—and, owing to a barrage of interest, often must deny—permission to use Logan’s many spaces. He manages the custodial, security, and facilities staffs. As he describes it, his job amounts to “making sure everything runs in here, from the elevators to landscaping and window washing to the schedule.”

“It’s always a good commute in when the phone’s not ringing,” he says of his morning drive from the North Shore, much of which he spends hoping all is running smoothly at Logan. But sometimes Chicago thunderstorms knock out the elevators the day of a conference, or the roof springs an evasive leak somewhere in the theater. The unpredictability is exactly what he loves about the job. People “don’t realize how much more to the facility there is,” he says, than just the tower sparkling above the tree line. It’s the constant activity that drew him back to the arts. “At the CSO it was great; it was always about the music, and that was my first love, the music. But you didn’t have visual artists in the building; you didn’t have a theater department.”

As the staff works out the inevitable new-building kinks, Redenius looks forward to turning over the day-to-day to his staff so he “can step back and work on some bigger picture things. Things we just haven’t had time yet to develop”: things like opening Logan’s café and working with the city to maximize parking availability. For now, Redenius and his staff continue to adapt. “We’ve learned a lot since we opened up. We continue to learn and we try to adjust to best accommodate everybody’s needs.” With those needs set to increase and explode in variety this fall, Redenius is going to spend more time on the floor and on the phone than in that music ensemble room where a basement drummer can take in a fifth-story view.—Colin Bradley, ’14

Pianos are living things, says tuner Ken Orgel, “always in a state of entropy.”

Piano forte

“I kind of came in with the piano in Mandel,” says piano tuner Ken Orgel. Since 1995—the year a University committee traveled to the Steinway factory in New York and came home with a nine-foot concert grand for the renovated Mandel Hall—Orgel has looked after most of the 60-some pianos in performance halls and practice rooms (and a few dorms) across campus, fixing squeaky pedals and sticky keys; retrieving pencils and cell phones from the instruments’ bellies; tuning the strings a few times a year. “Weather”—almost any weather at all, he says—“is your enemy.”

Orgel’s most recent charge is a fleet of new pianos at the Logan Center, of which the most majestic is another nine-foot Steinway grand, which required another trip to New York last year to audition a showroom full of instruments. “It was obvious to everybody which one really cooked,” says Orgel, who started tuning and repairing pianos 30 years ago out of pure necessity. He was a garage-band piano player just out of college with “no money and no job”—and a broken piano. Twenty-five dollars’ worth of tuning levers and wedge mutes became an improvised apprenticeship and, eventually, a career.

In a backstage storage room off the Logan Center’s 474-seat performance hall, Orgel pulls back the new Steinway’s padded cover to reveal a shimmering keyboard and a lustrous black frame. He can’t resist plucking out a couple of arpeggios and a high trill. Playing a well-tuned, well-built piano, Orgel says, is like cutting a tomato with a sharp knife: “It just slices right through.”

Besides the big Steinway, which will be wheeled onstage for concerts at the performance hall, another two dozen new pianos are scattered throughout the Logan Center, in practice rooms and group rehearsal spaces. The practice rooms are a needed addition, Orgel says, to those at the music department’s old headquarters in Goodspeed Hall. There, demand is so high that students and staffers often wait in line for available pianos. “This school has so many good piano players,” he says. “And a lot of them, they’re not even music students. You ask and they’ll say, ‘Oh, I’m a geology major,’ or ‘Oh, I’m in the English department.’”

Placing the cover back over the Steinway grand, Orgel notes that within the year this piano will need attention: humidity will expand and contract the soundboard, the strings will tighten and loosen, and the thousands of interlocking parts within it will begin, almost imperceptibly, to shift and change. “Pianos are always in a state of entropy,” Orgel says, “even when they’re in the factory.” Over the course of its life, a single piano will become several different instruments, its sound evolving as parts are repaired or replaced, strings are tuned and retuned, and its keys are struck again and again through song after song.

This evolution isn’t bad, Orgel says. “It’s almost how it should be.” He recalls an observation by composer and Chicago music professor emeritus Easley Blackwood, whose piano he occasionally tunes. “When I go in and tune for him, he says, ‘Ken, this thing is alive.’ Not, ‘How come this thing doesn’t work like it used to?’ The fact that things aren’t the same from day to day, that’s never depressing to him. And that’s right—things change, they aren’t the same. Just like he said: It’s a piano. It’s alive.”—Lydialyle Gibson

A still from Suspension of Belief—Part III (Work in Progress), a three-frame video about East Chicago, Indiana.

Back to his roots

In 1966 sculptor Virginio Ferrari came to Hyde Park from Italy as a University artist in residence, teaching at Midway Studios for the next ten years. His sons grew up in Hyde Park, and the youngest of the three, Marco Ferrari, U-High’93, went on to Ithaca College in New York and DePaul University in Chicago. Now Ferrari is back, beginning the second year of a UChicago MFA in film.

“Midway Studios has a lot of history kind of layered in it,” Ferrari says. Though returning to Midway Studios was “intriguing,” the Logan Center also attracted Ferrari. “The fact that there’s this new building that’s open to the public brings a lot of energy to the area.”

Given his deep connections to Midway Studios, which was, he says, “our own little world,” this spring’s transition to Logan felt strange to Ferrari. “Everything’s polished” there, he says, in contrast to Midway Studios, where it’s “a bit more raw.” Still, it’s a positive move for him. With an Arts | Science grant, he used the new projectors from Logan’s Digital Media Center to produce Opening, a video project with Jared Clemens, a biology graduate student.

In May the collaborators projected the seven-minute video installation onto the Surgery Brain Research Pavilion entrance, creating a 50-by-50-foot image—one that Ferrari hopes created an indelible memory for those who witnessed it. “If I can engage the community that way in terms of showing something positive, or reinterpreting a space for a moment, that can be a way for me to go into an area and have a dialogue,” Ferrari explains before musing, “It’s really kind of a song … something that’s a little bit more lyrical.”

Ferrari hopes to project his films more on campus and on the South Side. “We’re so connected via the Internet, but we’re kind of removed from public space,” Ferrari says. He gets his artistic impulse from his father, noting, “I grew up with the idea of how art can communicate with the environment that it’s in.” Virginio Ferrari has several sculptures on campus, including Pick Hall’s Dialogo.

This year Ferrari worked on a documentary film about East Chicago, Indiana, that premiered at the Logan Center in June. He and his family often passed, but never quite acknowledged, the industrial town on their way to the Indiana Dunes. Returning there, Ferrari sought to capture the alienation he felt during those childhood drives. “That’s kind of what my aim is—to try to connect space and identity.”—Emily Wang, ’14